“Sometimes, there’s a man, well, he’s the man for his time and place. He fits right in there. And that’s the Dude.”

-- The Stranger in “The Big Lebowski”

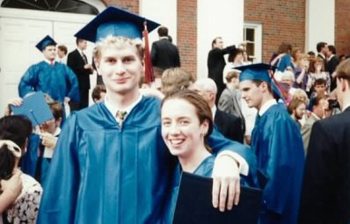

Late August 1988. Freshman orientation at Wheaton College. The old chapel.

On stage, several upperclassmen were enthusiastically leading the incoming class in a hand-waving, meant-to-be-inspirational rendition of Bobby McFerrin’s then-hit song “Don’t Worry, Be Happy.”

That’s when, if memory serves, I first met Rob Bell.

He was tall and skinny and funny. He rode a skateboard, was a fan of U2 and had this slightly off-kilter rhythm about him -- a stop-and-start way of speaking and an impish-but-kind, infectious laugh. I liked him immediately.

Rob went on to be the lead singer of a popular college band called _ton bundle (yes, with the underscore), while I immersed myself in the theater company and then, later, the student newspaper.

After our graduation in 1992, he moved to California and enrolled in Fuller Seminary, while I enrolled in Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, on the campus of Northwestern University.

Questions to consider

Questions to consider:

- What’s at stake in the debate over whether some people are eternally damned or whether God’s “love wins” and no one is lost?

- Philosopher Alisdair MacIntyre defines a tradition as a debate over what the tradition is. Christian theology has long debated the wideness of God’s mercy. Rob Bell is taking one side (perhaps the minority side) in that debate. How is the way we debate important? Is it as important as the outcome of the debate, or less so?

- If God were not to damn anyone, would that bring disrepute to God’s justice? If God were to damn anyone, would that call into question God’s mercy?

- Bell is suggesting our decision for or against Jesus in this life is still of paramount importance whether our eternal fate hangs in the balance or not. Can that possibly be true? If so, how?

Later, Rob became a pastor and founded Mars Hill, a “Jesus community” near his hometown of Grand Rapids, Mich. I became a journalist and wrote about religion for newspapers in Chicago.

In 1996, while working at the Chicago Tribune, I picked up The New York Times one day and saw a story by Gustav Niebuhr about an unusual service at a Grand Rapids church where congregants wrote down questions -- about anything and everything -- on slips of paper and passed them to the front, where the pastor tried to answer them honestly and biblically. No holds barred.

That pastor, described as “a recent seminary graduate,” was Rob.

“I think what people are yearning for is a place where they don’t have to have it all together,” Rob told Niebuhr. The Q&A service, he said, “is a safe place to wrestle with ... things.”

Fast-forward 15 years to a venue in New York City where Rob sat on stage before a standing-room-only crowd and fielded questions -- on a live stream broadcast worldwide over the Internet -- about his new book, “Love Wins: A Book About Heaven, Hell, and the Fate of Every Person Who Ever Lived.” In it, Rob re-examines traditional Christian notions of heaven and hell, landing at a conclusion that makes a lot of his compatriots in the evangelical community terribly nervous.

What if heaven and hell aren’t what we think they are -- up there and down there, eternal destinations somewhere other than planet Earth? And what if we were less certain about who goes where after we die?

What if God, in and because of God’s love for us, continues to give us the choice to embrace God’s love and grace and salvation, even after we die?

What if the really good news is that at the end of everything, God’s unfettered, immense, all-consuming love for all of creation -- including every single one of us -- in fact wins? What then?

Weeks before his book was released, Rob, the author of several best-selling books and creator of a series of über-popular spiritual short films called Nooma, found himself at the center of an ecclesial firestorm.

Several evangelical heavyweights, including John Piper, pastor of Bethlehem Baptist in Minneapolis, came out swinging.

“Farewell, Rob Bell,” Piper posted on Twitter -- three words that ignited recriminations, condemnations and vitriol against Rob.

Piper hadn’t read the book when he fired his shot. Neither had many of the critics who went on the attack.

Still, they called Rob a heretic. A universalist. A false teacher and a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Dangerous.

Even though I had some misgivings about where my old friend might be going in his new book, when I received an advance copy several weeks ago and sat down to explore it, I was pleasantly surprised.

The book is, to my eye, a powerful and enduring love note to and about Jesus the Christ. Its honesty and humility brought me to tears more than once as it affirmed and challenged some of the notions about salvation and grace and the hereafter that I’d held all of my life.

The pervading message is one of incredible hope, mercy, grace and love. God’s love for every single one of us and all of the creation God made and called “good.”

“Love Wins” is an instant spiritual classic. Rob, who is the first to admit he’s not saying anything new in the book, joins giants of orthodox Christendom such as C.S. Lewis, Chesterton and Chrysostom in their generous view of God’s offer of redemption and grace.

“I begin with the world that we live in right now and the simple observation that we can choose heaven and hell right now,” Rob told me by phone on Monday from New York City as he walked through Central Park with his wife, Kristen, between media appointments.

“I see lots of hell around me all the time. We all do. From greed to abuse to rape to genocide to exploitation of people who are vulnerable, we see this around us all the time. And then I see people choosing peace and joy all the time, and experiencing extraordinary peace that transcends anything you can get your mind around. ...

“Love creates freedom. Love always demands freedom. And so we are free to choose. And this freedom has consequences,” Rob said in our interview. “You can resist and reject this love, both in your own experience of it and in the ways in which you refuse to extend it to others, and you can receive it and pass it on to others, which seems to me to be the center of what Jesus keeps bringing up. ‘Love God. Love others.’ ...

“If we can choose these realities now, that Jesus came to offer us and show us, then I assume that when you die, you can continue to choose these realities because love can’t co-opt the human heart’s ability to decide,” he said. “But after you die, we are now firmly in the realm of speculation.”

What Rob writes in “Love Wins” is meant to be, in part, a corrective to twisted ideas about God and salvation held by “believers” and “nonbelievers” alike.

“I think it’s important to point out that, in the Hebrew consciousness, out of which the Christian faith flows, it was always, ‘Earth is where the action is’; and that for millions and millions of people in our modern world, the fundamental Christian message they were taught is about evacuation,” he said. “The highest form of spiritual practice is escape, essentially.

“That’s been hard-wired into their consciousness. Jesus is how you get somewhere else. And that is not the central narrative of the Scriptures, which over and over and over refer to this place as our ‘home.’ The central story is a God who loves the world, calls it good, and has set about a restoration/renewal/redemption/reconciliation/rescue effort,” he said.

“There is a paradox at the heart of who Jesus is. He is at once incredibly exclusive and incredibly inclusive. And you can’t resolve that tension, which his followers have been trying to do for thousands of years.

“So you can affirm his exclusivity and create and leave all sorts of space for the surprise of heaven and it’s OK. You can do that. And you’re not betraying him. I think that’s the real issue here -- that for so many people it’s either-or.”

The message of “Love Wins” and Rob’s humble thoughts on theology and the Jesus story -- inviting people into the holy, ongoing conversation of faith -- are a much-needed salve for an increasingly divided society, in which people attack each other about perceived cultural, political and spiritual differences rather than listening with open hearts and minds.

As we finished our conversation, I thanked Rob for what he has done and what he continues to try to do.

“This message, to me, is so clearly one of the reasons you were sent to walk among us right now,” I told him. “It’s so clearly you and it’s so clearly God. I’m just happy to be a witness to it. And I’m really happy to be able to hand everyone I know a book and say, ‘This is how much God loves you.’ So thank you, Rob.”

Sometimes, there’s a man ...