Few ideas are more incorrect in popular Christian thinking than the belief that the New Testament essentially renders the Old Testament unnecessary. To be sure, it’s not usually said straight out like this. But one nevertheless can see it clearly in the common idea that the God of the Old Testament is somehow different from the God of the New (wrath vs. grace), or in vague charges of legalism slung at those who try to obey some of the Old Testament commandments, or -- most prominently -- in the overall failure of Christian churches to read and preach from the Old Testament on a regular basis.

In a way, these problems are understandable. Reading the Old Testament is hard work for Christians. And many leaders have much else on their plate. Still, it is literally inconceivable that the New Testament can be well understood without the Old, or that Christians could develop the depth of theological leadership we need without understanding the most basic relation between the Old and New Testaments. The New depends upon the theological traditions of the Old for its innovation. The innovation, that is to say, is not against its preceding tradition but is a fulfillment of that tradition -- even as it reorganizes the tradition’s theological purpose around the person of Jesus Christ.

Of the manifold ways in which we could show how traditioned innovation names well the relation of the Old and New Testaments, we will focus on only two: the book of Leviticus and the Sermon on the Mount in the Gospel of Matthew.

First, Leviticus: Contrary to our initial impressions of an overly precise or even burdensome legal code, the book of Leviticus is at its heart missionary theology. It displays the intricate patterns of life that constitute the Jewish people, that mark them off from the non-Jews and, therefore, allow them to witness by their practices to their election by the God of Israel. Leviticus was, in short, a gift from God to shape the Jews into his people.

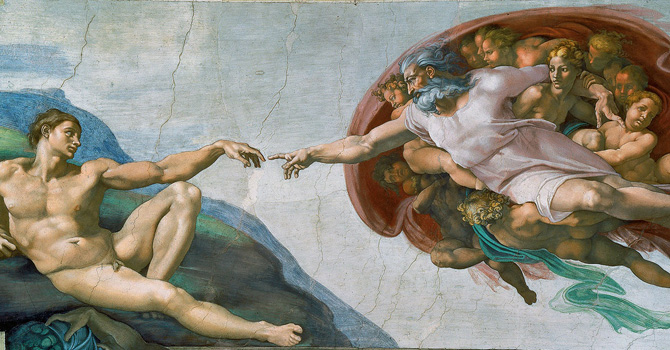

To realize that Leviticus was the fundament of Jewish practice and not casuistic prattle -- as so many Christians now cannot help but to take it -- is to become astonished at the almost complete absence of these kind of legal regulations in the New Testament, most especially those concerning the sacrificial cult (such as the different kinds of sacrifices we need to make, when to make them, with what animals and for what sins). Indeed, with the exception of the theology of Hebrews, and aside from a few oblique references to sacrifice, the entire sacrificial cult is missing from the pages of the New Testament. On one level, of course, the New Testament authors simply assumed the importance of the Temple and its practices, as did Jesus himself (think, for example, of the beginning and end of the Gospel of Luke where there is a marked emphasis on the Jerusalem Temple). On another level, however, Jesus’ death is interpreted as the “once for all” sacrifice (Hebrews 10:10), thereby implying that the entire cult was in a sense oriented toward this one death. Sin offerings no longer are necessary because, as the Gospel of John puts it, Jesus is the Lamb whose death takes away the sin of the world (John 1:29).

On the face of it, there is nothing in the intricacies of Leviticus, or anywhere else in the vast sprawl of the Old Testament, that could prepare for this. It is, quite simply, new.

Moreover, in Pauline theology and elsewhere in the New Testament (such as the book of Acts), the practice of the Law (Torah) no longer constitutes the primary socio-political or cultural boundary marker between Jews and non-Jews. Rather, being a disciple of Jesus Christ -- which of course entails joining the community that takes his name -- is the requisite criterion that now marks the people of God. Thus, in a twofold and profound sense, Jesus radically exceeds the Old Testament’s immediate theological range envisioned by the practice of Torah.

And yet the New Testament also claims that Jesus fulfills the Law and that there is no fundamental break with Jewish tradition. The transformation of Torah hence is tied more deeply to a unity in the purpose of God: to create a people who would be the light to the nations and thereby provoke them to worship the one true God. The same divine purpose that was at work in the giving of Leviticus has crystallized in Jesus. He is, as Luke formulates it both in his Gospel and in Acts, the light to the Gentiles. In Jesus Christ and the community that is gathered around its devotion to him, the moment for which Torah was given and exists has arrived. Jesus Christ, as Paul says, is the telos of the Law (Romans 10:4). In this case, drastic innovation discloses the inner logic and fullness of tradition.

Second, the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7): It is often thought that the six antitheses of the Sermon on the Mount provide examples of Jesus’ opposition to the Jewish law. In this common reading, “You have heard it said” is the tradition from which Jesus’ innovative “But I say to you” cleanly breaks. But this is simply false. It was not against the Law to require more than the Law itself required. In fact, nothing Jesus says runs contrary to the Torah in its written or oral traditions. What then is he doing? Matthew tells us explicitly just prior to the antitheses: “Think not that I have come to abolish the law and the prophets; I have come not to abolish them but to fulfill them” (Matthew 5:17). The antitheses, then, actually are instances of fulfillment of the Law.

Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount is paradigmatic for thinking about the link between a living tradition and the innovation necessary to keep it alive. Jesus discerned that the existing tradition (“you have heard it said”) was insufficient to the task at hand; the time had changed and the tradition as it presently stood no longer resulted in the formation of “righteous” people (“righteous/ness” is shorthand in Matthew for a life of discipleship in the kingdom; 5:20). What was needed in this new time -- the “Kingdom of Heaven” in Matthean parlance -- was a move into a more radical mode of life. Only so could the tradition stay in step with the telos to which it was oriented: thus “fulfillment” in Matthew means the way in which Jesus innovatively and faithfully extends Jewish tradition to accord with the change of the times -- the advent of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Questions to consider

Questions to consider:

- Why did God give the Law and also send Jesus?

- How does the New Testament teach us to think about the Old Testament?

- Why is the Old Testament necessary for right reading of the New Testament?