It’s about 1 o’clock on a Monday afternoon, and the Elevation Burger in Falls Church, Va., is packed with a hungry lunch crowd.

Every few minutes, an employee bearing a tray full of food emerges from behind the front counter, examines the ticket and calls a name: Dave. Mark. Pamela.

At a long table in the middle of the room, a gaggle of children in summer-camp T-shirts munch on burgers and fries.

The children don’t care that the burgers are organic, made from grass-fed, free-range cattle. Or that the fries are cooked in healthier olive oil. Or that the milk in their chocolate shakes is hormone-free.

“It’s yummier than McDonalds,” said Jan Aiello, whose two children, ages 6 and 9, are part of the group. “And it’s organic -- that’s important to me.”

It was equally important to Hans and April Hess, who opened this first Elevation Burger restaurant in September 2005. Nearly seven years later, the country’s first organic fast-food burger chain has grown to nearly 30 restaurants in the United States and the Middle East. Another 15 locations are slated to open this year and about 150 are in the development pipeline.

At first blush, the fast-food model seems an odd choice for a company with a heavily organic menu, environmentally friendly construction practices and a commitment to recycling everything from burger wrappers to used cooking oil.

But for all its flaws, the industry had key qualities the Hesses were looking for: affordable prices, accessibility to families, fast service.

Their challenge? To incorporate what was good about the fast-food industry with their own desire to do right by the planet and its people. And because they had a mortgage to pay and a family to support, they had to achieve that social good while also making a profit.

“The Earth is something we should be taking care of, not systematically destroying,” said CEO Hans Hess, 40. “I felt that God calls us to be stewards of creation, people who take care of it, so that was the driving force behind Elevation Burger in my head. I was going to try to do this completely opposite of the way the industry does it. I’m going to try to do this responsibly.”

‘I wanted to get this food to people’

Hans Hess’ love affair with burgers started young. He and his mother, Dee, who’s now an administrative assistant at the company, would sample hamburgers wherever they went, intent on finding the very best one.

Still, crafting the perfect burger was a long way off for Hess. Raised in Carmel, Calif., he majored in physics at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo before earning a master’s in theology at Dallas Theological Seminary. He intended to become a missionary with a nondenominational evangelical organization and, back home in California, began raising money to support a mission trip to Siberia.

About halfway through the process, he developed a severe case of insomnia. For six weeks, he was lucky to get an hour of sleep a night.

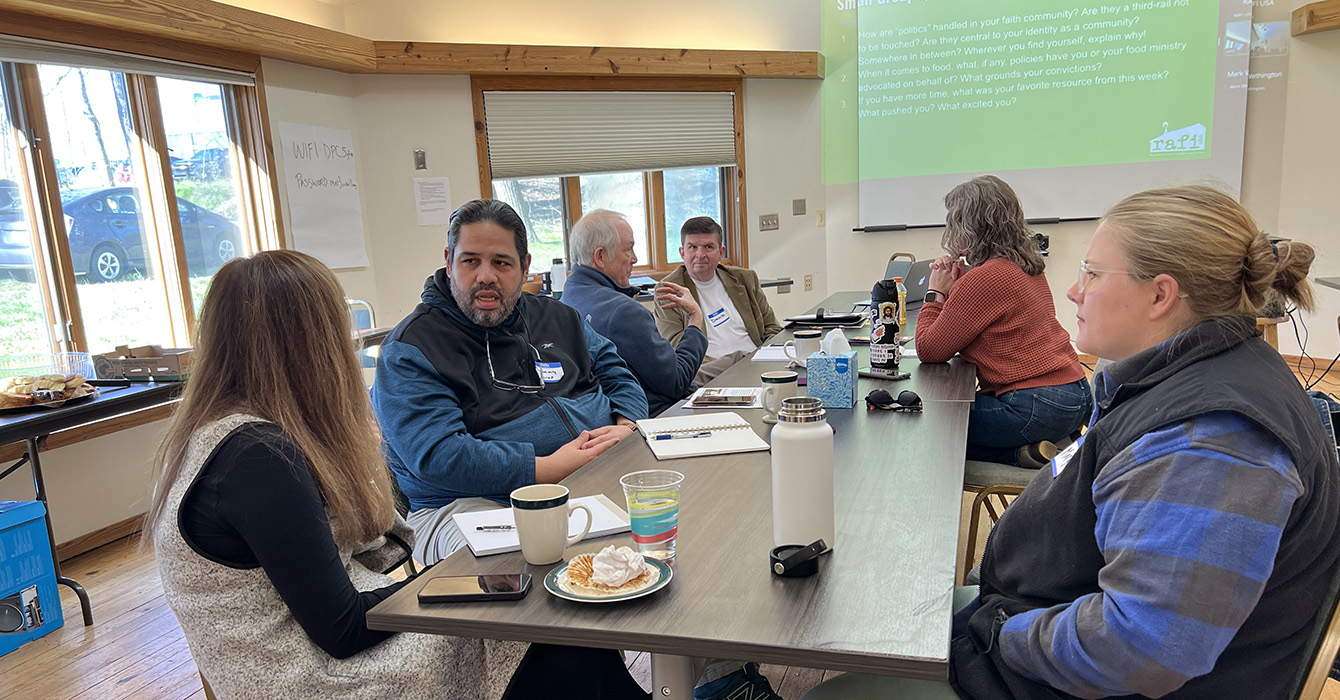

Questions to consider:

- In what ways did Hess fulfill his earlier dream to be a missionary? What does mission look like today?

- How can a Christian entrepreneur balance faith and making a profit? Is there a point at which they become mutually exclusive?

- Hess took an existing business model he considered broken and found positive values to build on. How would you redesign your institution? What are the core values to build on?

- How transparent is your organization? To what extent can those you serve see “what’s going on behind the counter”?

- How can the church help businesspeople think about and integrate faith and work?

“It was awful. So I prayed about it. I just didn’t know what to do. And it just kind of came to me that the idea of going overseas was probably a really bad idea,” said Hess. He decided not to go -- and promptly slept for 14 hours.

Not long after that, he moved to Washington, D.C., where he went to work for a congressman from Michigan.

There, he read a report that suggsted a link between the widespread use of antibiotics in livestock and the rise in deadly, antibiotic-resistant infections in people. In crowded feedlots, cows are fed corn to fatten them up quickly and antibiotics to ward off infection. Research suggests that the practice contributes to the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria such as MRSA, a strain of staph that kills about 20,000 Americans a year.

The potential connection between the country’s food supply and the failing health of its citizens made Hess queasy.

Hess later took a job with a real estate consultant, but the food-safety issue nagged at him. He and wife April, who are members of The Falls Church (Anglican), often bought organic groceries, but there weren’t many organic restaurant options -- and certainly none for people on a budget.

“There was no mass outlet for the kind of food I wanted to eat, so when I had the idea for Elevation Burger, that was the whole point. I wanted to get this food to people and make it affordable,” said Hess, who first suggested the idea to April around Thanksgiving 2002.

Their first thought was that “somebody should do this.” Then, April Hess said, they realized, “Why should somebody else do this? We should do this.”

It wasn’t the missionary work that Hess once considered, but the effort still felt like an expression of his faith, he said.

“I had a sense that it was a faith/God-directed calling from the moment I had the idea,” he said. “First, because stewardship of creation is such a big part of the idea, but also because there was and is so much about the idea that mediates or transmits God’s blessings, in the way sons of Abraham should.”

The couple wanted the restaurant to be accessible to the average family. So they pursued the fast-food model but with two key differences: Everything would be fresh, which meant no heat lamps or precooked patties. And the ingredients would be top-notch, which meant prices would be slightly higher than the average fast-food joint.

“Using those two rules, we navigated through supply and operations issues fairly quickly,” Hess said.

Because the restaurant’s mission would be to offer a better, “elevated” product, they called their idea Elevation Burger. Hess conducted market surveys, something he’d done regularly as a real estate consultant, to gauge demand for organic fast food. Respondents overwhelmingly wanted meat that was free of antibiotics, pesticides, hormones and other chemicals, as well as vegetarian and vegan patties. This reassured them that they weren’t the only ones interested in the idea.

“It was something I thought the world needed and deserved. It wasn’t just an interesting project. I felt it was something God called us to do,” said April Hess, who was a banker before becoming the company's chief financial officer. “Most people who start a successful business don’t sit down and say, ‘How can I make a lot of money?’ We sat down and said, ‘This is something we’d like our family and friends to have access to.’ We have deeply believed from the beginning that this is what we are called to do.”

Supported by his wife’s income, Hess quit his job with the real estate consulting firm in 2004 and devoted himself full time to getting Elevation Burger off the ground. He scouted for locations and spent months in his own kitchen experimenting with how best to fry potatoes in olive oil, how big the burgers and buns should be, and even how many pickles were appropriate and how thickly they should be sliced.

In September 2005, they opened the first Elevation Burger, located in a Falls Church storefront, sandwiched between a medical supply shop and a day spa.

People, planet, profits

Selling great-tasting burgers was key to attracting a loyal fan base, but from the beginning, Elevation Burger focused on a triple bottom line: people, planet and profits.

“Yeah, we want to make money. You’ve got to do that,” Hess said. “But we want to try and show it can be done in a way that takes care of the planet, this idea of stewardship of God’s creation, and that also respects the people who are involved in producing the product and making it happen.”

Employees earn benefits and a living wage, and they’re cross-trained in all areas of running the restaurant.

The kitchen was designed with maximum efficiency and transparency in mind. Customers, who get their food in about six minutes, can watch exactly what’s going on behind the counter. Employees grind the meat daily and grill the 3.2-ounce patties on energy-efficient griddles.

The Hesses wanted the entire operation, not just the food, to be environmentally conscious. So used cooking oil is donated for conversion to biodiesel fuel. Guests walk across eco-friendly bamboo floors and dine at tables made from compressed sorghum beneath fluorescent and LED lights. Many of the franchise’s newest buildings have LEED certification, meaning that not only are the materials green, but the method of construction is environmentally friendly as well.

James Stewart was 18 when he first started working at Elevation Burger as a cashier. Now a college graduate and the company’s creative fund and brand manager, he jokes sometimes that Elevation Burger is “changing the world, one organic burger at a time.”

“People are having access to or coming into contact with organic for the first time through this familiar, comfortable vehicle that is the hamburger,” Stewart said. “This is creating a bigger awareness of organic and ultimately creating a larger demand for organic food in our country, which is going to help shift the paradigm on how we view food.”

The average cost of a double burger, drink and fries runs about $12 at Elevation Burger. That’s more than a typical fast-food meal, but customers who understand the collective benefits of eating organic products don’t seem to mind, Hess said.

“Obviously, one of the things that didn’t work for me with the fast-food model framework that’s out there is the intense focus on getting the product as cheaply as possible. Because in that model you don’t really care how the animal was raised,” he said. “Our cows live in a pasture all their life. They don’t live in a feedlot ever. They don’t ever get antibiotics or hormones. Their feed is completely free from pesticides. The nutritional profile of the meat is outstanding.”

In 2008, Elevation Burger began franchising its operations. Ultimately, said Hess, he’d like to expand it to 500 outlets. The company’s practices have transferred well to the larger scale so far, in restaurants from Miami to Bahrain. Hans Hess said that franchisees go through an extensive training process that focuses not only on how to make the signature burgers and organize workers into shifts but also on the ethics behind the company’s brand.

Hess’ sister, Cynthia, a retired math teacher, oversees the training program, along with Elevation Burger’s human resources department. Ultimately, she said, the company hopes to introduce more people to organic food and drive enough demand for it that organic agriculture replaces factory farms.

“We realize it’s idealism, but we’re not going to stop fighting for it,” she said. “It might not get achieved in one generation. Give us two, then. We’re relentless. This is what we believe.”

Elevation Burger’s style may never entirely replace traditional fast-food practices, Hans Hess said, but at the very least, the company hopes to offer diners a better alternative. It’s been great to be able to show burger fans and entrepreneurs alike that running a successful business and caring for the planet are not mutually exclusive, he said.

It’s a good lesson -- and legacy -- for children Elisabeth, 6, and Hans, 5, as well, he said.

“I want them to have a planet to be able to do business on,” Hess said. “I think that that is sort of buried in the theological assumption that there may be a really good reason God wants you to take care of the planet. It’s not just a blind command. There’s rationale for it. How are you going to have future generations if you don’t do the things to make the future generations viable?”