More than any other cuisine in the U.S., barbecue is often served with a side of religious fervor. The atmosphere and language that surround barbecue, the words and phrases that food critics and aficionados use to describe it, are often rooted in things spiritual and holy.

Food writers, for example, gush about “the scales falling from [their] eyes” after eating superlative barbecue nowhere near Damascus (at least not the one in Syria -- although maybe the one in Georgia). Pit masters are likened to preachers, and their barbecue pits, pulpits from which the holy “word” is served.

A barbecue joint in Denver proudly claims to serve “nondenominational barbecue.” Rather than taking sides in the sectarian divisions of the barbecue world and committing to a particular style -- Kansas City, Memphis, North Carolina, South Carolina or Texas -- this restaurant takes an ecumenical approach, drawing from each to create something new, something “quintessentially Coloradoan.”

But a now-retired Raleigh, North Carolina, newspaper columnist made the straightest connection between barbecue and religion, simply calling his state’s barbecue “the Holy Grub.”

Sacrilege? Not really. Barbecue fans and commentators are onto something. They recognize that religious words have power to describe things near-inexpressible, things that are important and that matter. Church matters, and so does food -- especially, to many people, barbecue.

In short, whether adjective, noun or verb, “barbecue” has a theological dimension that is deeply enmeshed in church culture, especially in the African-American church.

I don’t know when the words “church” and “barbecue” were first joined, but the “church barbecue” has a rich and long history in the United States. In the late 18th century and the early half of the 19th century, Protestant Christian evangelists sought creative ways to introduce the gospel to the masses. Some hosted outdoor gatherings that lasted several days, featuring preaching, worship and feasting.

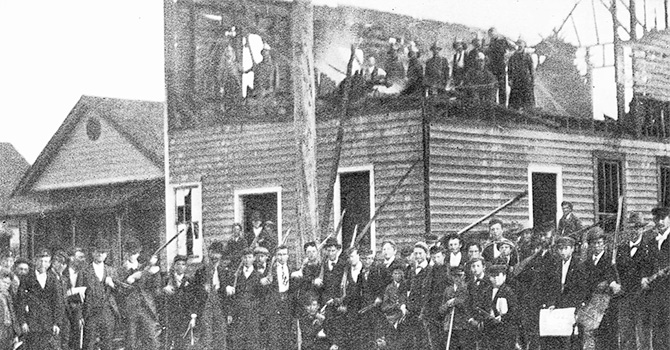

Known variously as “camp meetings,” “protracted meetings” and revivals, these outdoor events paired perfectly with barbecue, the ultimate in alfresco dining. Like church itself, the best and earliest barbecues, with their scented smoke and sizzling meat, demanded a crowd.

Before grocery stores and restaurants, you couldn’t simply order a barbecue sandwich or even a rack of ribs. You ate barbecue only when an entire animal was cooked.

To avoid waste, camp meeting organizers took a “Y’all come” approach to both their faith and their food, inviting the general public to partake, often free of charge. The invitees were happy to oblige.

Camp meetings were particularly effective in the American South, where most African-Americans lived.

Barbecue, at its theological and culinary best, reinforces a church’s important social role and enhances the communal experience of God.

During the long period of chattel slavery, church buildings were scarce, and many slaves were unchurched. Many slaveholders discouraged proselytizing among their slaves, because Christianity conferred humanity on enslaved people.

Camp meetings, however, gave both free and enslaved African-Americans (at least those who got the master’s permission or managed to “steal away”) the opportunity to enjoy so many things that make us human: unfettered worship, the freedom to associate on equal terms with people of a different race, and an adequate, even abundant, amount of food. In the racial caste system of the antebellum South, African-Americans too often lacked all these and more.

So we come to the meat of the matter -- a theology of barbecue.

Barbecue, theologically speaking, is about bringing people together, creating a space where we can recognize the divine in each other and reaffirm our individual and collective humanity -- here, now, not waiting until the afterlife.

Though the camp meetings drew large crowds, they were by nature temporary events. Yet the religious fervor they unleashed was channeled by evangelists into the more permanent work of church planting. As congregations were formed and buildings built, the creation of worship spaces had tremendous religious and social implications for African-Americans in the rural South. As the historian W.E.B. Du Bois noted in 1903, “The Negro Church [was] the first distinctively Negro American social institution. … The Church became the center of amusements, of what little spontaneous economic activity remained, of education, and of all social intercourse.”

Socially and culturally, across the South, rural church events were usually the only game in geographically isolated towns. Even so, pastors knew that they faced competition from worldly distractions. Religious events with superlative food gave them a competitive edge. Although a variety of foods were served at these church-hosted meals -- sometimes called “dinner on the ground” -- barbecue was often the favorite, the source of the most salivating memories. As more and more rural churches hosted barbecues, these faith-filled events reinforced to congregants that they weren’t alone, that they belonged to something greater than themselves.

Later, when rural African-Americans migrated to urban areas, they felt a new form of isolation, more social than geographic. Longtime African-American urbanites snubbed the newcomers as unsophisticated country bumpkins and often refused to accept them. Once again, the black church came to the rescue, replicating familiar and welcoming social customs, adapting them to an urban setting. A hand-dug barbecue pit in a country field was exchanged for a church basement with a modern kitchen. The tools and techniques changed, but the theological goals remained the same.

Thus, happily, as African-Americans moved to urban areas across the country, they brought barbecue with them. In city after city, countless black churches held barbecues to build community and raise funds for church operations. Though white churches undoubtedly did the same thing, local newspapers took a peculiar interest in reporting on African-American church barbecues.

My own church, Campbell Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Denver, was widely known for its barbecue by the early 1900s and was often the subject of newspaper articles.

“Barbecue Attracts Crowds: Southern Feast Given by Campbell A.M.E. Church to Raise Money on Its Debt Proves a Success,” blared a headline in the Denver Times of August 27, 1902.

For the event, Campbell Chapel hired Columbus B. Hill, Denver’s pre-eminent barbecue man of the day, a chef who clearly understood the religious dimensions of barbecue.

“This method of serving meat is descended from the sacrificial altars of the time of Moses when the priests of the temple got their fingers greasy and dared not wipe them on their Sunday clothes,” Chef Hill told the paper. “They discovered then the rare, sweet taste of meat flavored with the smoke of its own juices.”

Amen, brother.

A “multitude” watched Chef Hill cook, the paper reported. As the article confirms, even the act of cooking barbecue -- anticipating it, savoring the moment when it can be eaten -- can create community.

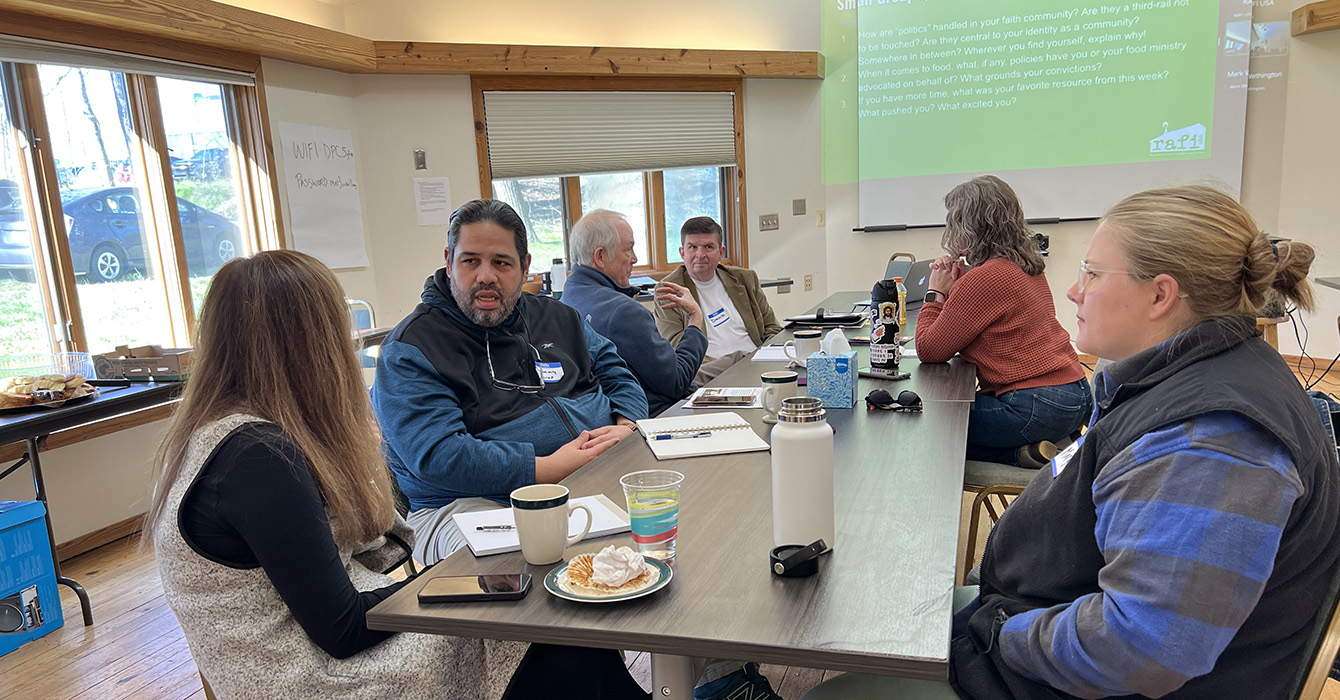

In many ways, the challenges that evangelists faced in the days of the camp meetings are the same challenges that churches face today.

How do we spark someone’s interest in God? How do we hold together a sacred community? What are the best ways to keep someone coming back?

Barbecue may not be the perfect answer to all of these questions. But I can vouch for its success in bringing people together to embrace a faith-filled life. Barbecue, at its theological and culinary best, reinforces a church’s important social role; it enhances the communal experience of God, sharing in his bounty through a delicious meal.

Now, pass the barbecue and hold the sauce. As with the burnt offerings of yesteryear, properly smoked meat needs no help bringing us closer to the divine!

Questions to consider

A field guide to African-American church barbecue joints

Even today, many church-connected barbecue restaurants are still in existence, with preachers tending the pits. Interestingly, most are linked to African-American churches. If there is a “Holy Land” for this sort of thing, it’s Texas. As Psalm 103:15 reminds us, “The life of mortals is like grass, they flourish like a flower of the field” (NIV) -- and the same holds true for barbecue joints! Please call to confirm that the place is open before you make the trip.

· CB’s Bar-B-Que, the Rev. Jerry Miller, Peaceful Holiness Church, 728 N. 14th St., Kingsville, TX 78363, 361-516-1688.

· Davis Grocery & Bar-B-Q, the Rev. James Davis, 400 S. Robinson St., Taylor, TX 76574, 512-352-8111.

· New Zion Missionary Baptist Church Barbecue, the Rev. Clinton Edison, 2601 Montgomery Rd., Huntsville, TX 77340, 936-295-3445.