Clergy need to be prepared now to work together on the day when crisis strikes their local community, says the Rev. Dr. Alvin Edwards, founder of the Charlottesville Clergy Collective.

“We live in a day and age where anything goes, and we have to be prepared,” Edwards said. “We have to be ready to assist as believers.”

A coalition of Charlottesville clergy and laity from across a variety of faith traditions, the collective helped lead area residents and others in opposing white supremacists who came to the city last summer. Edwards was prompted to form the group two years ago, after the 2015 shootings at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, when he realized that trust was lacking among Charlottesville clergy.

“There were no relationships, because everybody was in their own little fiefdoms,” Edwards said.

Since then, the collective has brought together Charlottesville clergy from across a variety of faith traditions, building trust and new relationships. These new bonds proved valuable when white nationalists poured into Charlottesville last summer to protest plans to remove statues of Robert E. Lee and other Confederate generals.

One of the lessons for clergy and churches in other cities is to know one another and work together across faith traditions, Edwards said.

“If the religious community is going to make an impact, they need to do it together,” he said. “The Christian community can’t do it by themselves, because of the number of faith traditions that are out there.”

A native of Joliet, Illinois, Edwards is pastor of Mt. Zion First African Baptist Church in Charlottesville. He has a B.A. from Wheaton College, an M.Div. from Virginia Union School of Theology and a Ph.D. from George Mason University.

He spoke to Faith & Leadership about the origin of the collective, and its plans for the future. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: To start, what is the Charlottesville Clergy Collective, and how did it come about?

The collective is a diverse group of men and women from different denominations in Charlottesville.

After the shootings at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, I got together with a few pastors -- primarily white, and a couple of African-Americans -- and asked them, if what happened down there happened here, how many thought I would call them?

And the answer was none. So we started talking about that and about how there weren’t any real relationships [among us]. Previously, there had been a ministers’ conference in Charlottesville, but it had broken up.

So we didn’t have a ministers’ conference per se, and I really wasn’t trying to start one. But it was something that I thought we needed to be aware of -- what if something like Charleston did happen?

We talked about that, and we decided to keep talking. We talk more and more. We spend more time with each other. We get together. We talk about some of the issues we’ve been going through.

Q: The collective’s website says that in this process, you and the other pastors realized there wasn’t a lot of trust among themselves, which would be necessary if the group ever had to respond quickly to a crisis. Why the lack of trust among the pastors?

Well, in order to trust one another, you have to have a relationship. But there were no relationships, because everybody was in their own little fiefdoms. They kind of just do what they do. It was not about what can we do together to make a difference; it was about what we’re doing individually.

Q: How did you and the other pastors go about changing that? How did you build trust?

Conversations. We didn’t come together for that purpose, but it helped bring us closer together.

As we talked and learned more about each other, that helped to build trust and to draw us closer together. Our goal was for each of us to try once a month to get together with someone in the clergy collective and go to lunch or breakfast or have a cup of coffee, to get to know each other, to learn about each person, who we are, what we do, what makes us tick.

The only way you’re going to learn to trust each other and to believe in each other is to talk. You’ve got to spend time with each other, and it has to be time where you really get to know each other, where you open up and can vent and have a safe place to talk to someone. But more than that, it’s about the example you want to set for members of your congregations.

Q: So tell us about last summer, when word spread that white nationalists and other white supremacists would be coming to Charlottesville to protest plans to remove statues of Robert E. Lee and others.

When we found out about that, we talked about what we wanted to do and came up with a three-pronged approach.

One was to completely ignore them. Another was to meet at a church and gather for prayers, and a third was to confront them.

With the plan to completely ignore, we had an event at the downtown pavilion where we had a couple of groups come down and sing and a number of prayers by different religious traditions, and then I made a challenging statement.

The people who wanted to be close to the church met at First United Methodist Church and had prayers and songs.

And some of us marched down the mall. Others marched down the street where the Ku Klux Klan was going to be.

So we tried to hit it at all three different angles, because there was no agreement on doing it the same way. We had to take different approaches to address it, and we did.

Q: How did it play out? Many press accounts noted the very visible presence of clergy.

It was challenging, dealing with the death of Heather Heyer and a number of hurt feelings. There was just a lot of grief that went with all that. It was not a piece of cake. It was very trying.

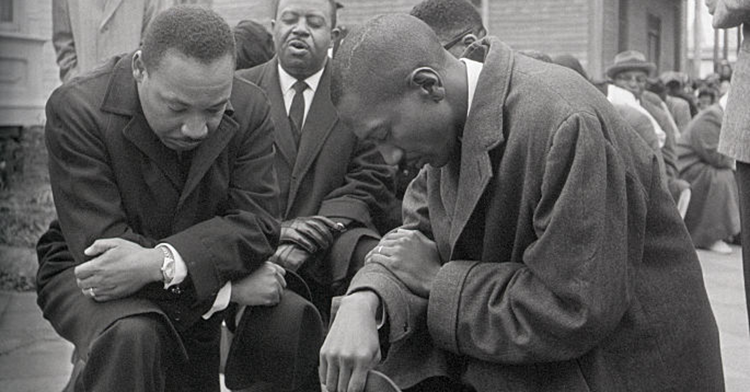

The clergy that showed up came in their robes to make sure that people knew clergy were present, that they were present. There was nothing that they wanted to demonstrate any fear for. They wanted people to know they were for real.

Q: Did the collective go through any preparation or training in the preceding weeks?

There was a training by a group called Congregate Charlottesville. It’s a separate entity from the clergy collective. They are a younger group and wanted a different approach. Their approach was direct action against the Ku Klux Klan and the neo-Nazis and white supremacists. Some people didn’t want to go that route, but some did. So everybody had to do it the way they felt the most comfortable with.

Q: What difference did the collective make that week?

The biggest difference is that it demonstrated to the city that the clergy were concerned about this group coming into Charlottesville trying to label us as a bad place. It let the community and the citizens know that we are here and that we are involved and that we’re going to stand up for what we believe is right as clergy.

We’ve been very focused on trying to make a difference in our community and showing unity and respect among different faith traditions.

Had the clergy collective not been there, I’m not sure what message would have been sent or what people would have heard. It probably would have continued to be that “those preachers are only interested in what they call ‘spiritual things’ rather than social things.”

For me -- I should say, for us -- it was about more than that. It was about letting people know that we care genuinely about them and that we’re interested in their well-being.

I believe we had some effect. I don’t know how to measure it or to even ascertain what it was completely.

But one thing for sure, we were there to comfort people and to let people know that we care and that we were there to assist them to make an impact, and that we also were not going to stand for hatred and injustice to continue to perpetuate itself, and that we wanted those things that represent injustice, hatred, slavery, etc., not to be around either.

Q: You’ve been long active in political and civic life in Charlottesville. You’ve served on the school board and on the city council. You were mayor from 1990 to 1992. What’s the proper role for a pastor in the public square today? How does a pastor navigate that space, particularly in today’s political climate?

African-American pastors have always been involved in political life. I was raised like that. My late father-in-law was a pastor who was very involved in the civil rights movement and justice and making sure that there wasn’t discrimination in hiring.

He always fought for that, so I guess I was kind of a chip off the old block. I was taught that way, and it’s what I believe.

For me, wherever there is a need [to speak out], I believe preachers, pastors, need to do it. Some Caucasian pastors would have a hard time doing that because of their congregation. But my church has been, for the most part, very free and supportive about letting me do those things I feel led to do.

My preparation came from years ago. My standing up for that which is right came as a result of learning from my late father-in-law/pastor in Joliet, Illinois.

Most churches are going to have their challenges. Mine are minor, to be honest with you. I’ve been here 36 years, and it’s been a pretty good run.

I have no regrets. Virginia was not on my radar screen when I first started looking for a church. But I believe I’m where God wants me to be, and as long as I’m where he wants me to be, I do have a strong sense of peace of mind about what I do and my involvement in the community.

God has just given me so much favor with so many people in Charlottesville. I’m thankful for the opportunity that God has brought my way, but I think any pastor, if you care about your community, you’re going to do things.

For example, I have a real issue with how we keep looking past children who cannot read on grade level. It bothers me. Even when I had to do the funeral service for Heather Heyer, one thing that I challenged them with was, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if all of us took a child and made sure they were on grade reading level?”

I said, “If we did that, think about the impact it would have on our educational system, just to teach one child how to read or to make sure that they are on grade reading level.”

That would just make a significant difference.

Q: What lessons does the collective offer for other churches in other cities?

One, if the religious community is going to make an impact, they need to do it together. The Christian community can’t do it by themselves, because of the number of faith traditions that are out there.

But together, we could make a greater impact on the lives of people.

The other lesson is that we’re not in this for ourselves. We need to make sure that people know that we care about our community and that we want the best for our community.

Q: Is there a lesson as well just about getting ready and being prepared? Did you ever dream that something like this would ever happen in Charlottesville?

I never dreamed it, but it happened. And just like the tragedy that happened the other day in Sutherland Springs, Texas, who would have ever thought that somebody would walk up in the church [and start shooting]?

We live in a day and age where anything goes, and we have to be prepared. When things like that happen, we have to be ready to assist as believers. You can’t get hung up on the fact that you belong to this church and others don’t.

You’ve got to do what you believe the Lord would lead you to do, and that is to help people as you live.

My motto is, “If I can help somebody as I pass along, if I can cheer somebody with a word or song, if I can show somebody they’re traveling wrong, then my living shall not be in vain.”

That is, my goal is to help people. No matter where you are or what your walk is with God or anybody else, my goal is to help people and to make a difference in their life.