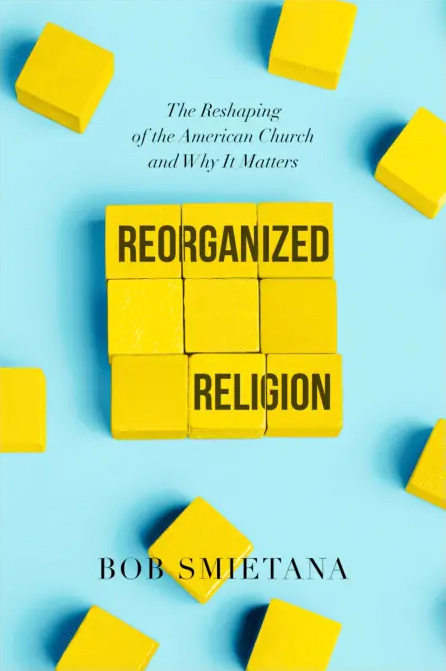

Bob Smietana has a message for Christian leaders: Don’t mess things up. It’s too important.

Smietana, who is a national reporter for Religion News Service, is the author of “Reorganized Religion: The Reshaping of the American Church and Why It Matters.” In the book, Smietana makes an argument for why churches are vital — not just for churchgoers but for society as a whole.

In a world where polarization and fear often dominate conversations and relationships, Smietana says, people need what the church has. Sometimes that means skills such as asking forgiveness, admitting that you need help and understanding that you can dislike someone yet still see them as a person of worth and a neighbor.

Churches also have the capacity and expertise to offer food to the hungry, shelter to the unhoused and large-scale relief efforts.

But as the number and the size of churches decline and fewer and fewer people are members of congregations, that is slowly disappearing. And it won’t be replaced, Smietana said.

“It’s like religious climate change,” he said. “What churches do right now will really make a difference long term. Because if you let it go, it isn’t coming back.”

Smietana spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Sally Hicks about the book and the trends he has observed in more than two decades of reporting on religion. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: I think this idea about what the decline of the church means is something that’s underappreciated. Aside from the way it matters for Christians, what impact does this have on the rest of society?

Bob Smietana: A lot of it has to do with social capital and charitable work. Eboo Patel, the head of Interfaith America, when he goes to a college, he says, “OK, what if all the religious groups in your community disappeared? Who does the food pantry? Where does the AA meet? Where do you hold the weddings, the funerals? When there’s an emergency and you need a shelter, where do they set up? Where does the voting go on?”

Right now, Florida’s crazy [recovering from Hurricane Ian]. Thousands and thousands of trained, prepared, dedicated disaster relief volunteers are down there. They’ve got training; they’re cooking food, they’re cleaning out all the debris, they are taking trees off people’s houses — they’re doing all this work for which they have all volunteered time.

They spend a lot of energy preparing: “This terrible thing’s going to happen in the world. How do we help?”

You don’t notice until they’re gone, right? But then they’re gone. So even, say, a food pantry — most churches have some kind of food ministries, and the food bank distribution system relies on that.

Right behind me [on screen] is a congregation in Chicago that we used to attend. They just closed down. They’re selling the building. They housed a really extensive food ministry, which will be gone. So people, when they come to that neighborhood, where are they going to go to get that food? Well, someone else has to do that, but we have to think about that, and nobody has.

Even from a city zoning perspective, do you want to have a church building there? Do you want to have condos? Do you want to have schools? What’s going to be in the place of that? So it’s a lot of unseen but essential work.

F&L: And there’s a sense that quietly, one by one, as they disappear invisibly to others, there won’t be a replacement.

BS: There won’t be a replacement. We know things are going to disappear, and there’s no plan to replace that. There’s no plan to deal with the leftover things, the buildings, the schools.

There’s no place to think about, “What’s going to replace those schools? What’s going to replace those food pantries or counseling programs or homeless services?”

Almost every community has some kind of overnight shelter plan. What do you need for an overnight shelter plan? You need space. You need a place to cook warm food. You need access to volunteers. And what does a church have? All those things.

It’s the human capacity. Lots of people want help when there are disasters, and social media can be great for doing that. But they’re not always organized over the long term. So you can collect money, but if thousands of people show up to save Florida, they don’t know what they’re doing.

They might do more harm than good. They’re in an unsafe zone. They also have a lot of money to collect that no one’s keeping an eye on. They can be harmful by trying to help.

F&L: I was a reporter in Florida when Hurricane Andrew struck. I remember those giant coffee urns set up by the Baptist Men. I thought, “If I were in a hurricane, the first thing I would want was a hot cup of coffee.” I also saw the giant piles of winter coats that well-meaning people had sent there in August.

BS: So [relief organizations] have massive semitrailers with water. They have massive semitrailers with food. They are working with the Red Cross. The Red Cross is delivering all the food, and other groups are doing parts of this.

They’re all working together — the volunteers who come who know what they’re doing and aren’t going to break anything. And they can remove that tree on your house and give you a sense of getting back to normal.

F&L: What about the idea that organized religion has done more harm than good or has done enough harm that it’s not worth saving?

BS: That’s a good question. Those are good arguments. Ryan Burge at Eastern Illinois University has an idea that faith groups make the world less awful. Which is a good way of saying they don’t always make it better, but they often fill that place between where government services end.

But there are harms that people do, and there are continued harms that people do. So religion is only as good as the people in it. But disorganized religion and disorganized and disconnected spirituality are awful also — actually worse. With no boundaries, spirituality can be really awful.

But it causes harm because they’re human. It’s not like if you get rid of religion things will be better or we’ll be more willing to work together. All the incentives right now are to say, “Who do I hate, and how do I hate them?” And the organized religion folks are at least saying, “We should work together, make this world a better place.”

Most of our institutions, even when they fail, are still doing good. The Southern Baptists are an example. The Southern Baptists are [against] Hillary or they’re [engaged in polarized] politics as a voting bloc. And they’re showing up in Florida in large numbers. So they are doing both.

I’m arguing that they should think more about making the world thrive and less about the partisan polarization.

The idea is that the church is supposed to at some point be saying, “Don’t be an awful person.” And they congregate people: “We have a list of people who decided not to be awful, and they gave us a bunch of money, and we’re going to send them, use this money and their energy to go out and make the world less awful.”

That’s not an unsubstantial thing.

F&L: Talk a little about “the mini and the mega” — the fact that most people are in large churches yet most churches are small. You argue that this is a problem.

BS: I started reporting on religion about 1999. Actually, I worked with a denominational publication. But when I started, the median congregation was 137 people.

With 137 people, you can do a lot of things. Pay a pastor, maybe pay two pastors, pay for your building, a choir. You can have an ongoing, sustainable institution.

In 20 years, that number is 65 [pre-pandemic]. That’s the median number. So half of the churches in the country have under 65 people. That’s an enormous change.

Then we have a consolidation of people, the Walmart effect, at the larger and larger churches. So people are going to churches that are bigger and bigger, but the congregations themselves are smaller and smaller.

It’s hard for people to pay attention to this. You might think you’re in a normal-sized church with 200 people. If you’re in a church with 200 people, you are in one of the bigger churches in America. You really are. But you don’t think that, right?

The smaller churches are often in neighborhoods, in communities. Sometimes they’re in places where people used to live but don’t anymore. But most big churches are not in the neighborhood.

Congregational governance means people have to talk to each other, which encourages them to be connected to people, to influence them. But often in the bigger church, it is more staff-driven, and the people are there to participate and give, but they don’t have any say in what they should be doing or how it should operate.

If you teach people that they just give and attend and serve but not comment or not give leadership, then they are not going to give leadership. They’re not connected to the larger institution. So all the power is in the pastor.

F&L: So people in a church who are engaged in governance are learning something about how to engage and influence others?

BS: They’re learning soft skills, right? Where else do you learn how to hold a meeting, disagree, but you find consensus? You’re not going to find that in a school board meeting. School board is, “Who do I yell at the loudest?”

[Churches] can be contentious. But they’re not always contentious. Not every general convention or every quarterly business meeting is contentious. In December, when they’re approving the pastor’s salary and what they’re going to do about how to run the church, it usually goes very easily.

They may ask questions, and they poke at it. It’s not outright rancor, unless there’s a hard issue. But still, they stick with each other, and they walk through it, they vote, and they stay together.

F&L: When you used the phrase “soft skills,” it reminded me of the Black church tradition of Easter speeches. That’s a kind of soft skill that happens at every level of church life.

BS: Yes, and you learn about the people that you’re with. You know, with 137 people, you’re going to have a shared confession, you may have asking pardon for sin and getting forgiveness, absolution. But you’ll also have the prayers of the people. You get an update: “How’s Aunt Suzy’s little baby? How’s Jeff and his cancer? How are the folks doing?” So you learn about the people in your community as people.

But if you’re in a church with 10,000 people, you can’t have a public kind of prayer. You can’t know 10,000 people.

F&L: Another thing that I found interesting was in a section describing the “nones” as falling into two groups: secularists and civic dropouts.

BS: This is around the work of David Campbell and John Green, their book “Secular Surge,” which is really helpful. Big, big difference between intentionally secular people saying, “We’re going to organize together.” They often are very civically active. Most of the civic action is in politics.

Then there are people who are just dropouts. They’re unaffiliated everywhere, not just church. They’re unaffiliated with their community. They may have very little family. So they’re disconnected in a lot of ways from everyone. So that’s a big difference.

There are about as many nones as there are evangelicals. Which one is more effective politically? The evangelicals, because the nones are not organized. If you don’t want to be affiliated with people, then you’re not affiliated. You don’t want to work together, not because you’re a bad person, but because you don’t organize well as a bloc.

So what is the word “congregation”? It comes from the word “congregate,” which means be together, do things, do work together. Actually, some secular groups do that, but they don’t always do that, because there’s not a common value of joining.

Projections for the future essentially put nones and Christians at about 40% of the population [each]. So they’ll be the two largest groups, but they’ll be almost the same size. So how do they cooperate? How do they get along? And how do the religious people whose political philosophy is at odds with the political philosophy of the nones reach them with a religious message?

F&L: What you’re really making an argument for is not just religion but religious institutions. You write at the end of the book about what happens next, and you don’t offer any prescriptions, but what do you think should happen next?

BS: As a reporter, I’m not a theologian. I’m not a pastor. I’m not a church leader. So part of this is to explain, “Here’s where you are.”

I think a church leader will come along and say, “Why is my church falling apart? I have failed.” They might think, “If we had hipper music ...” or, “If we had different theology, or [were] more progressive …” or, “If you were more conservative, you’d succeed.”

It’s all about realizing you’re in a different universe, and that all these institutions people serve are not going to be around much longer.

I was at this meeting with Eileen Lindner, and she said, “Why don’t people go to church? Because they’re dead.”

We all laughed, but that’s part of the truth, right? It sounds morbid, but the church-going population is disappearing. They’re all dying off. That math doesn’t work. But people don’t see that. It’s not the world we grew up in.

It’s not the church’s fault that it’s in the shape it’s in. All these changes were coming to the church no matter what. I do think that people are going to have to be like, “All right, it’s going to be different. How do we live out our values for the whole community and not just our community?”

You’re going to have to adapt to it, and it’s going to mean loss. Often, I think, church leaders and congregations have ideas about how they’re going to change the world. Which is important. But sometimes building a congregation that can work together to change the world gets lost.

The work that churches do now will have long-term effects. People are still interested in spirituality. They’re interested in community. People like Jesus; they like Christian values. And they’d like it more if they saw it more.

Churches and pastors have enormous wealth of resources on how to adapt to new places, new countries, new circumstances. So they can draw on that. You know how to reconcile people. You know how to bring people together. What the world doesn’t need is more people united in fear.

Everyone is depending on you — and they don’t even know it. Society is depending on you.