I had never given much thought to Charlottesville’s monuments to Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson — they were not my heroes, so I paid them little attention. But the leadership of a teenager changed my perspective on the statues. In the spring of 2016, Zyahna Bryant, then a Charlottesville High School student, petitioned the Charlottesville City Council to remove the Lee statue and rename Lee Park, both of which served as daily reminders of the Confederacy.

I agreed with her when she said that we should not honor those who fought to keep African Americans enslaved. My eyes were opened by her words, and I came to realize that if such statues offended her, then they were offensive to others.

Her stance was prophetic, and the conversation she started led to the City Council’s decision to remove the Lee statue and expand community conversations on racism.

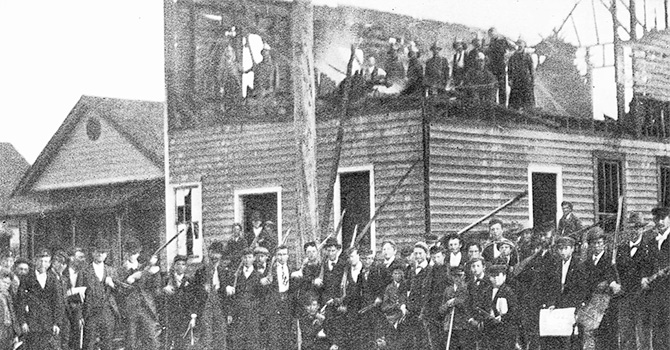

What I witnessed in the aftermath of that decision was also eye-opening — a reminder, to those who needed one, that racism and hatred are not frozen in statues but are alive within our communities. On Aug. 12, 2017, the Unite the Right rally turned deadly; Heather Heyer was killed and 35 others were injured when a white supremacist drove his car into a crowd of counterprotesters.

White nationalists were rallying against the removal of Confederate statues. On that Saturday five years ago, I witnessed people in militia uniforms carrying assault rifles, a protester firing his gun in the crowd, and others assaulting counterprotesters with pepper spray, batons, and vulgar and racist language.

This event was a reminder that something is amiss not just in Charlottesville but all over this country, extending to the highest levels of government. I was disgusted and disturbed to hear then-President Donald Trump say how he really felt — “There is blame on both sides” — and then later try to change his tune when faced with mounting criticism of his words. What a horrific example from a leader of our country.

That was then. Five years later, how have things changed? Here are some of the ways the events of that August weekend have affected me and my community.

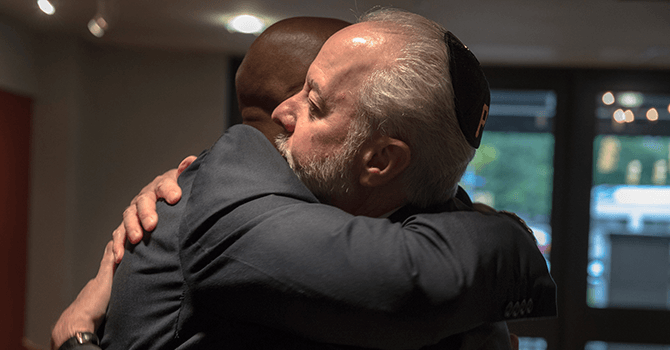

Relationships and trust have deepened among members of the Charlottesville Clergy Collective, which had brought people together from all religious walks of life to oppose injustice and prejudices. After the tragic 2015 shooting at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, a colleague and I had gathered a group of white and Black faith leaders to discuss that horrible event and to talk about racial justice in our community. These meetings had evolved into the group we came to call the CCC.

In 2017, in preparation for the events we knew had been planned for Aug. 11 and 12, the CCC had encouraged leaders of various faith traditions to organize prayer vigils — worship services to provide hope and strength to the community and to encourage resistance against white supremacy. Our collaboration called for a level of trust and multifaceted strategies among diverse populations, institutions and communities that span and bridge many divides, including racial, ethnic, political, socioeconomic and religious. On that Saturday, we were among the counterprotesters who marched.

As a result of Unite the Right, the CCC became a more cohesive group, and more action oriented. We now focus on attitudes and inequities. We have reading groups that challenge our thoughts and ways. We hold dinners for members of our churches and other religious groups, because food, like prayer, brings people together. We have had as many as 200 people at tables discussing racial issues. The CCC was not just a flash in the pan in 2017; we continue to meet and work toward a “beloved community” as envisioned by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Beyond our religious communities, the events of Aug. 11 and 12 have had an impact on our arts, culture and educational institutions. The Jefferson School African American Heritage Center, in our restored African American school, has expanded its arts, culture and local Black history offerings.

The local schools have rewritten their social studies curricula to make sure we are telling the full story of our history. Live Arts, our local volunteer theater, has consciously included more women and Black playwrights in their offerings and has added a diversity officer to their staff.

The main difference now is that we are a more proactive community regarding racial equity, and that includes changes at the University of Virginia, the flagship state university that calls Charlottesville home. The school has expanded programs dealing with equity and diversity. A monument recently built and prominently placed honors the enslaved workers who built the university. It has elevated their and other Black voices and revealed their contributions to this community.

Changes in our community are very much a work in progress, and I am sure there are many I have not mentioned, with others still needed. But I believe the changes I have highlighted have had a positive impact on the city of Charlottesville and those of us who live here. We are in a better place than we were five years ago.