John Burwell gets plenty of reminders that the volunteer work he does has become a matter of life and death. All the Homestead, Pennsylvania, man has to do is glance at his phone to see the importance of his efforts to educate the Black residents of local neighborhoods about the value of being vaccinated against COVID-19.

“I opened up my phone yesterday and [saw that] four people I knew died from it,” Burwell said in late December. “That was in one day -- one day!”

Painful moments like that keep him vigilant as an unpaid health deputy with the Neighborhood Resilience Project, a faith-based Pittsburgh nonprofit with a mission to strengthen communities affected by trauma. His University of Pittsburgh training on vaccines and his employment as a community program specialist at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh make him well qualified for the role.

But Burwell’s health science knowledge isn’t what gives him credibility on the street. That comes from his reputation as a trusted man of faith. He’s one of seven ministers in his prominent local family, so when he warns community members about a dire threat and the value of vaccination, he finds that people are willing to hear him out.

“They’re thinking that clergy and ministers would give them the truth and not lie to them,” said Burwell, who leads music programs at Second Baptist Church in Homestead, a community 7 miles from downtown Pittsburgh. “I let them know that I’m coming at this with a heart of concern about humanity. It’s not just a concern about an individual but about our existence on this planet.”

How have you built trust with your neighbors?

Pittsburgh’s faith-based outreach adds to what’s being described as an all-hands-on-deck push to educate Black residents about COVID-19 vaccines and the crucial role they can play, especially if most opt for vaccination this year.

That, however, is a big “if.” Many are wary of being vaccinated even though COVID-19 has disproportionately ravaged racially marginalized communities for reasons ranging from higher rates of chronic disease to crowded housing conditions that can make social distancing difficult.

No demographic group has been more disinclined to get vaccinated than Black Americans, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted late last year. Only 42% of Black survey respondents said they would definitely or probably take the vaccine if it were available then. Across the survey overall, 60% of respondents said they’d definitely or probably get vaccinated.

Reasons for mistrust

This leeriness among Black Americans is rooted in the past and in the present. Burwell notes that many in his community know about the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, a 40-year U.S. Public Health Service study (1932-1972) that deceitfully withheld treatment from 399 Black men with syphilis in order to study the disease’s progression.

Black skeptics worry that they might be similarly abused in the name of science with emerging COVID-19 vaccines.

“It’s not just about Tuskegee,” said the Rev. Paul Abernathy, the executive director of the Neighborhood Resilience Project. “A lot of people had a history of clinical abuse in their social networks or even have personally experienced this in the current health care systems. This history of clinical abuse, I think, heavily informed perspectives on the vaccine.”

Many have felt mistreated by health care providers who haven’t taken their concerns or symptoms seriously, according to Shondell Davis, community trauma healing specialist at the Social Impact Center, a nonprofit housed at Boston’s Roxbury Presbyterian Church. Or they’ve been victims of racism in other settings and fear that vaccines might be used to harm them.

“It’s all about what you’ve experienced,” said Davis, who’s involved in the church’s multipronged campaign to inform Boston’s Black communities about COVID-19 vaccines. “Say you went to a white doctor and he didn’t tell you something or you felt you weren’t treated right or you weren’t diagnosed correctly. Why would you trust a white doctor telling you to take this vaccination?”

But vaccine leeriness could prove deadly. Experts warn that resistance to vaccination programs in racially marginalized communities could endanger far more than the unvaccinated individuals. It could also truncate virus-fighting efforts across the board.

A population that gets vaccinated at half the rate of another could, just one year later, have a 6 times higher infection rate, and a higher death rate as well, according to Dr. Barney Graham, deputy director of the Vaccine Research Center at the National Institutes of Health and the chief architect of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine.

“One of my greatest fears right now is that one year from now, if African Americans avoid this vaccine, … the disparity [in infections] is going to be 6 times,” said Graham at a January online panel hosted by Roxbury Presbyterian. “I really don’t want to see that happen.”

Local church leaders, including pastors and respected lay leaders, are stepping into this wary atmosphere. They’re wielding hard-earned moral authority to vouch for unfamiliar experts. The hope: if faith leaders can open pathways for reliable vaccine information to reach everyone, countless lives may be saved.

Who are the ambassadors for your church or organization in the larger community?

“For most people, the more information they have, the more likely they are to trust, particularly if that information comes from somebody that they trust -- and I think that’s where the clergy come in,” said Sharon Knight, interim executive director at Stop the Spread, a nonprofit that mobilizes the private sector to help vulnerable communities build defenses against COVID-19. “They’re trusted community leaders who people look to for advice and for counsel, not just as individuals but as a community.”

Building on experience

In Pittsburgh and Boston, the approaches aim to build upon what’s worked in the past. For the Neighborhood Resilience Project and Roxbury Presbyterian, the goal of faith-based outreach is to equip neighbors to voice their questions, consider experts’ opinions and make informed decisions for themselves and their families.

What’s more, the faithful in both cities are drawing on systems that have proved effective for distributing information to traumatized communities in the past. Now they’re re-imagining and repurposing those systems for a public health crisis paired with daunting logistical challenges.

Roxbury Presbyterian, a predominantly Black congregation, is leveraging its pastor’s background in broadcasting to reach across Boston. The Rev. Liz Walker is a local celebrity, best known for her prior career as a popular Boston TV news anchor.

For years, her 150-member church has hosted open mic events that give victims of trauma a rare platform to tell an audience how they’ve suffered.

Participants have recounted trauma’s effects on their lives, whether from an abusive home, wartime deployment or mental illness. Eliciting stories to find solutions has become a trademark of Walker’s ministry style.

How do your leaders provide reassurance in times of confusion or anxiety? How might that look different in matters that are not strictly theological?

Now she is gathering up her neighbors’ questions about COVID-19 vaccines and putting them to experts. Her first in a series of vaccine education webinars drew 2,800 viewers to question Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

In early January, she teamed up with the Rev. Dr. Gloria White-Hammond, a Black pastor and medical doctor in Boston, to interview Graham, the vaccine architect, who is white, and two local Black physicians who specialize in infectious disease.

“People are asking questions that I think are very valid,” said Walker, who has also published editorials and recorded a public service announcement as part of Roxbury Presbyterian’s vaccine information outreach.

“The problem isn’t that there’s not enough information. It’s that there’s too much information,” Walker said. “So we say, ‘Let us help you get the information -- we’ll have these ongoing sessions -- and then make your own decision. But here’s what we know: this risk [of vaccination] is not as great as having the disease.’”

The webinar gave experts a stage to deliver crucial information. Graham, for example, explained that the vaccines weren’t made from scratch at breakneck pace. Rather, they are built on more than a decade of related research that was repositioned to battle the novel coronavirus.

A matter of equity

Some of the questions drove at why those involved in vaccine distribution should be trusted.

“Why do you trust that the common good is being served by pharmaceutical firms that we already know overcharge and have historically overcharged for necessary drugs like insulin?” Walker asked, reading a viewer’s question.

The query was directed to Graham, whose work is linked to Moderna. Rather than defending the pharmaceutical company, he responded by sharing a personal story.

“Maybe the best way to express it is that my African American daughter, who lives in Los Angeles and is an architect -- she enrolled in one of the vaccine trials,” Graham said. “This is somebody I really care about. She trusted her daddy, and I trusted the vaccine enough that I thought it was safe enough for her to test.”

That panelists and their clergy interviewers were hoping to change minds was no secret. A poll taken at the webinar’s start found that 74% of viewers said they were planning to get vaccinated. By the end, that number had climbed to 89%. Panelists smiled and clapped upon seeing the results, which were framed as a sign of progress to save lives.

“We need everybody to get this vaccine, and I would say that I am feeling encouraged,” White-Hammond said.

She said she’d resolved not to let the last breaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and now Susan Moore, the Black physician who called out her own racially biased treatment for COVID-19, be in vain. Using vaccines to defend against the COVID-19 threat is one way, in her view, that Black communities can work toward equity.

Learning from other epidemics

In Pittsburgh, vaccine-conscious faith leaders have built on a methodology that took shape in response to another epidemic: gun violence. The Neighborhood Resilience Project’s Abernathy, a Black Pittsburgher himself, launched the NRP 10 years ago as a faith-based nonprofit to pursue “trauma-informed community development.”

What they learned about confronting gun violence, among other health risks, gave them a blueprint for tackling a crisis no one expected.

What relationships do you have in your community that you might build upon in a crisis?

“What we learned is to approach gun violence just like any other disease,” Abernathy said. “There were three big elements of this epidemiological framework. One was to interrupt the transmission of the disease. Second was to prevent the future spread of the disease. And third was to change community norms. …We took that and we adapted it to COVID-19.”

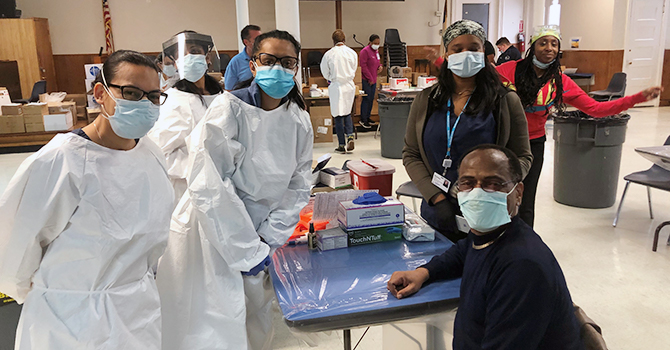

When the pandemic hit, the NRP trained 118 volunteer health deputies in cooperation with the University of Pittsburgh and other partners. Those deputies fanned out into 15 predominantly Black communities in the Pittsburgh metro area, where they discussed virus safety protocols. They also successfully recruited Black participation in the University of Pittsburgh’s trials last summer for the Moderna vaccine.

An infrastructure of relationships

That infrastructure has now been retooled for vaccine education. Many of those same deputies, motivated by faith, are now going back to individuals they’d already contacted to share the good news of coming vaccines and how getting vaccinated can be beneficial.

The vaccine education effort has drawn the likes of Rhonda Lockett, an ordained elder in the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Before the pandemic, she would venture out into the Hill District, where abandoned houses are a perennial sign of hard times, wearing a bright yellow health deputy vest that told the world, she says with a laugh, “Here comes sunshine!”

She’d hand out feminine hygiene products or share information on getting health insurance and lining up other types of support.

What new partnerships have you developed during the pandemic? What other opportunities might you pursue?

Now staying home, she leverages banked trust by calling those neighborhood contacts, getting referrals and answering questions about COVID-19 vaccination.

She spends up to six hours a week making calls that typically last 10 or 15 minutes each. She often shares that she’s motivated by her faith.

“I do bring up God, and that’s accountability for me,” Lockett said. “A couple of calls have included prayer. A 95-year-old lady said, ‘I am extremely afraid of COVID. Would you pray with me?’ And I was delighted to do that.”

Lockett feels that her efforts are making inroads. Many of those she calls assure her they’ll get the shot, she said. But patterns of resistance pose ongoing challenges. Lockett says she finds the most skepticism among young adults, who present as overconfident about their health prospects and distrustful of government.

“In the community I’m working, there are so many young African American men who are angry and have distrust,” Lockett said. “What works to reach them is to be kind and to be soft in your speaking. … Towards the end, I say: ‘You know what? God loves you, and so do I.’ That gives them something to think about.”

As faith leaders bring their moral clout to bear, they’ll have more opportunities to get creative as vaccine operations ramp up, according to Stop the Spread’s Knight. Pastors might turn their own vaccinations into role model moments, for instance, by being photographed getting the shot, sharing the photo on social media and publicly saying why they did it. They can also offer their trusted church facilities as convenient sites for getting vaccinated.

“Clergy can reach out to [pharmacy or health clinic] partners and say, ‘Hey, I’d like to have a vaccination day in the parking lot of my church,” Knight said. “Helping remove barriers to access by creating alternative destinations where people can access the vaccine is another important role the churches can play.”

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- How have you built trust with your neighbors?

- Who are the ambassadors for your church or organization in the larger community?

- How do your leaders provide reassurance in times of confusion or anxiety? How might that look different in matters that are not strictly theological?

- What relationships do you have in your community that you might build upon in a crisis?

- What new partnerships have you developed during the pandemic? What other opportunities might you pursue?