I will never forget the final day of the 9/11 recovery of the World Trade Center site. We at St. Paul’s Chapel were saying goodbye to each other with tears and love in an unscathed church on the precipice of Ground Zero, where 5,000 of us had given our lives for nearly a year to serve 15,000 recovery workers.

Out of that welter of emotion, my colleague Ulla said:

We’ve all been training here, and we’ve had a very powerful training. It’s as if we’ve been given a torch. Now we have to go out to the world ... and take it from here to where it needs to go. ... Let’s not forget the lessons we learned from this. Let’s not go back to where we were. There is no going back anyway.

A decade later that torch burns brightly. The powerful leadership paradigm we came by intuitively during that daunting year is making its way into the wider church. This paradigm can be clearly recognized in a movement that goes by several names. Some, like Juanita Brown of the World Café Community, call it social process activism; others call it transformational social leadership. The focus of this emerging approach to ministry -- the goal of universal human thriving -- will help church leaders align how we are church with why we are church.

Our collective experience of death-and-resurrection on 9/11 shaped our approach to ministry.

Running from the black cloud of toxic, burning debris and facing almost-certain death, we encountered people who were paralyzed with fear. We pulled them along with us and witnessed others reaching out to help those who were injured or numb. This “school of death” spontaneously opened us to see ourselves as part of one another. Suddenly we saw each other as part of one human life whose existence is forever incomplete without your life.

Days after being nearly buried alive in the collapse of the North Tower, I wrote:

We want to be the opposite of the horrendous destruction staring at us across the street, and move farther and farther away from the possibility of participating in any way with terror’s repetition.

The ad hoc leadership team formed at St. Paul’s quickly decided to steward the operations of our newly born religious community in the spirit of the first responders. Their care was our mission.

During life-changing days as chaplains inside the pile, we observed up close the whatever-it-takes commitment to human life lived by the firefighters. This commitment -- unleashed in us all -- became the antidote to the artifacts of violence, chaos and suffering we continued to see and smell. With every choice we made in our ministry, we aimed to embody this commitment to life.

Resources for the social process paradigm:

According to the somatic branch of the social process school of leadership, the four essentials for human thriving are safety, dignity, relationship and resilience. Although we were not aware of these at the time, 200 hours of recorded interviews I conducted during and after the recovery confirm this is exactly what participants in the ministry experienced in the chapel.

To create these conditions we did exactly what social process leaders say to do: we practiced. We developed practices that helped us to continue to see each other the way we saw ourselves on 9/11, consistently repeating behaviors every day that generated and regenerated in our 20,000-person congregation the conditions of safety, dignity, relationship and resilience that we yearned to offer to all.

The architecture of the community we fostered became one of mutual storytelling, testimony and holy listening. When you came to serve at St. Paul’s, a central part of what you did was to listen to the stories of workers who came in to thaw after shifts digging through rubble by hand for human remains. We listened to one another talk about why we love what we love, why we care about what we care about, why we do what we do.

At St. Paul’s we listened 24/7. If you entered the chapel at 3 a.m., you would see thousands of people sitting in the pews in pairs whispering to each other in hushed voices in the candlelight. We listened as if nothing else in the world mattered but this person, this life, this sacred text from life being shared. Just this one practice regenerated daily all four of the nutrients needed for human thriving: safety, dignity, relationship and resilience.

But this was just one of hundreds of practices happening simultaneously in the little chapel that stood.

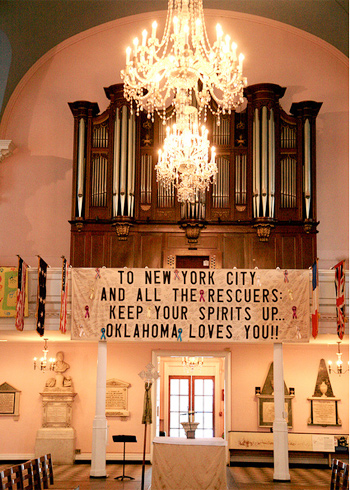

We also devoted daily energy to the practice of creating space, utilizing thousands of visible signifiers of appreciation for those who were caring for life.

Stations of compassion surrounded the sanctuary: George Washington’s box pew in front housed a podiatry clinic; on the north side massage tables stood in the side aisles; three meals a day were served on the west-side portico; clothing and pharmaceuticals were stacked on the south side where musicians also performed soothing music around the clock.

At the altar on the east side, the Eucharist was celebrated every day at noon.

And every interior surface, floor to ceiling, was covered with letters and drawings from children from around the world. These were constantly replenished, with thousands more arriving weekly.

Social process practitioners claim that practices like these generate the conditions for human thriving, that sufficient focused energy is gathered and sustained by teams to achieve deep goals. This rings true to our experience in ministry. We had sufficient energy to work in shifts around the clock for nine months -- to support those who were reclaiming a million and a half tons of debris and the remains of thousands of people who had perished.

Despite the enormity of pain and suffering, everyone described themselves as flourishing in the process. Now that’s a powerful leadership model.