Darren Walker is not interested in just giving money away. As president of the $13 billion Ford Foundation, there is plenty to give, but Walker wants to be sure the money his organization grants does more than serve an immediate need.

As he explains in his book “From Generosity to Justice: A New Gospel of Wealth,” Walker is advocating a different vision of philanthropy. He wants to address the systemic, root causes of needs, to acknowledge that charity alone does not solve the problem, and to encourage leaders to bravely call out injustice and the institutions that perpetuate it.

Walker also calls for humility from those with the power to give, encouraging them to recognize that they may not be the experts every situation requires.

Walker also calls for humility from those with the power to give, encouraging them to recognize that they may not be the experts every situation requires.

He writes: “Going forward, we can shift our mindset and turn our impulse toward charity into a more intentional pursuit of justice. To do this, we must shift our attention to the voices of those most affected by injustice, because they are the ones who understand the problems best. They are not objects of charity, but drivers of change. Because justice is inclusive, we must never forget that the project of creating a more just world belongs to us all.”

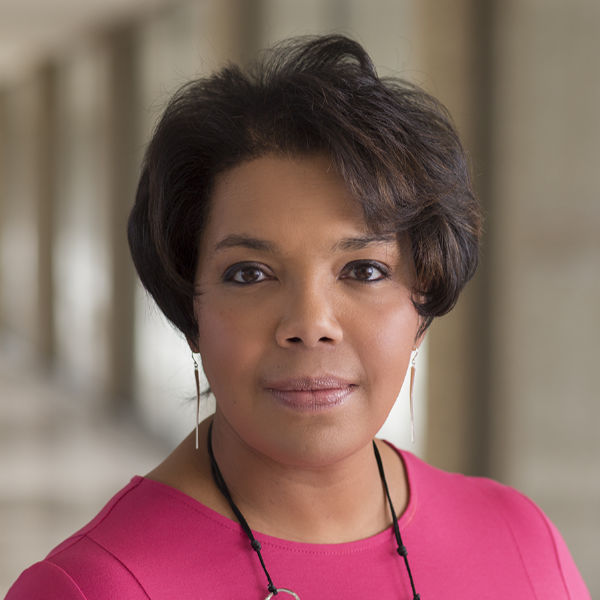

Walker spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne while at Duke University to deliver the Terry Sanford Distinguished Lecture. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Professionally, you’ve gone from corporate to nonprofits to philanthropy. What was your call? What has put you on that particular path?

Darren Walker: I started on Wall Street in part because when you grow up poor and working-class, you actually never want to be that again. I felt the call of Wall Street, to be totally candid, to be able to, for the first time in my life, have some semblance of financial and economic security, because I also knew that given the circumstances in my family, I had responsibilities for younger siblings, and ultimately for my mother.

I’m really happy that I took that route initially, but I knew Wall Street was not a calling for me or a career; it was a path to making a good financial living. It was not a path to a good life.

The path to a good life I found in Harlem, where I met the Rev. Calvin Butts at the Abyssinian Baptist Church, one of New York’s oldest African American congregations. He is an extraordinary leader and had created a very exciting new initiative called the Abyssinian Development Corporation, which was one of the first faith-based community development corporations in New York.

His vision and the vision of Karen Phillips, who was his co-founder, was that Harlem in the early 1990s -- which was considered a place of deficit, a place of deprivation and deficit people -- that that narrative needed to be turned on its head.

In fact, Harlem was a place of assets that needed to be invested in, whether those were human capital or physical capital or institutional capital. All of those simply needed to be invested in, and the return on those investments would yield a community that was thriving and more vibrant, with its residents being more economically secure.

That vision excited me, and it was also a way for me to transition from Wall Street and to take the skills and capacities I’d developed -- project management, an understanding of the capital markets, real estate finance -- and apply them to ideas and initiatives that I hadn’t thought about working on.

Those same skills I could use to finance low-income housing or to figure out the financing for a Head Start program or taking a tract of vacant land and turning it into a commercial center with the first commercial supermarket built in Harlem in literally [30] years.

Philanthropy happened very serendipitously, because I received a phone call one day from someone who said, “I’ve given your name to the president of the Rockefeller Foundation,” who had asked if she knew of anyone who worked on community development. Rockefeller had a major program on community development.

I was hired as director of the U.S. program, and it was a really exciting opportunity to transition to philanthropy -- not something that I thought I would ever do. I thought my work would be for some national organization working on urban redevelopment, for example. So to go to Rockefeller was an opportunity I could not let pass. I am so happy that I didn’t, because it turned out to be a transition to a completely different world.

I’d never want a career in philanthropy in the way in which sometimes people think about philanthropy -- as a sector with power and money you get to give away and decide who gets it. I’m interested in philanthropy because it potentially can be a pathway, or it potentially can be a platform, for investing in more justice and fairness in our society.

I’m really only interested in philanthropy because it can be an accelerator of social change, [because of] the way in which philanthropy can influence influencers and can help inform policy and public policy, and hopefully invest in the voices of people who are often left out or left behind -- to validate, valorize and hopefully institutionalize, in an organizational way, their priorities, their aspirations.

F&L: You mentioned in another interview the contradictions that are sometimes present in the room, where you can be at a black-tie event and at the same time very much aware of those in your world who are in more humble circumstances. How is that perspective reflected in your leadership? There's a lot of pressure in that.

DW: When Du Bois talked about or wrote about the duality of the Negro in America, I think all of us carry that experience. I certainly do, because I’ve lived with privilege and without privilege. Living with privilege can be intoxicating for some and can allow one to lose touch with the things that matter most, and certainly lose touch with the life and experience that some of us are encouraged to get away from.

For those of us black folks who have succeeded, sometimes the narrative was one of escapism -- you’ve got to get out. There are these narratives that to better yourself, you must leave behind your community, your people and those with whom you had proximity when you had less privilege.

My view is that proximity matters, and we experience that proximity in different ways. For some of us, we’re proximate because of our family circumstances. We’re proximate because in spite of the fact that you may be getting dressed for that black-tie event, your phone rings and your mother is telling you that cousin Buster died and his wife doesn’t have the money for the funeral, and so she’s going to kick in half the cost.

The reality is that there are people who live on a precipice, and they are one event away from a financial crisis, for example. Most of us who lead foundations aren’t proximate to that kind of reality. We are proximate in our work, because every day we come to work and hear stories of poverty, of destitution, of deprivation. But for most of us, when we go home, we’re not on the phone with some family member we’ve got to make sure we’re helping because they’re in a crisis or just getting through the day.

I do think there is more diversity than ever in philanthropy, but we have a long way to go. I think we will be a better sector when there are more people of diverse backgrounds, lived experiences, race and gender.

F&L: I’m wondering whether your personal faith has informed your work in any way.

DW: The idea of social justice, for me, is rooted in theology. It’s rooted in the Scriptures and transcends denomination. Whatever your faith, there is a tradition of justice, and it’s why today in philanthropy I am sometimes discouraged by the response of some to the idea of social justice philanthropy.

I’ve had more than one foundation president say to me, “My board isn’t comfortable with all of that ‘justice’ language you use. Just talk about opportunity, or talk about leveling the playing field, but don’t talk about social justice.”

When did, in a nation with so many people who identify as religious -- how did “social justice” become such a contested term? For me, getting at social justice requires of you a belief that things can get better and that there is goodness in the world, that righteous anger is allowed through that lens.

I think that faith is often put in the context of peace and grace and hope -- and those are our ideals. But anger, rage, deep disappointment are also rooted in faith, because Jesus was outraged by some of the injustice he saw.

F&L: That dovetails with your book. In it, you write about the soul of the country and being in a time when the only acceptable response is courage. How can faith leaders lead in that? What do you see is their role in moving from charity to justice? There are a lot of wonderful churches with soup kitchens and tutoring programs, but they are not seeing their role beyond that.

DW: The things that our faith institutions do are essential to the success of our democracy and our civic life in this country. And so we need our soup kitchens. We need them to provide after-school programs for young people and homelessness services.

We also need our faith leaders to address the structural issues, the systems that produce so much deprivation, and to look at not just the symptoms but to address the causes, because most of the ills of our society are produced by systems and structures that are often designed to get us the outcomes we’ve got.

Your church should be commended for helping formerly incarcerated men and women return into society. Those same churches should ask why do we have such a system of mass incarceration in the first place, where we are the most incarcerated nation in the world on a per-capita basis, and why is it that most of the people in that system are black and brown and poor white people?

I believe that justice requires that we do both -- that we address the symptoms, but that we also address the root causes. Courage is the willingness to speak up and speak out, putting your own social capital at risk, and that is hard to do these days, because courage is often discouraged.

Courageous leadership is often discouraged because most leaders today think first about managing risk. There’s an entire risk management industry that surrounds us and that discourages us from taking courageous positions on important issues and that encourages statements that say nothing.

Speeches, platitudes and words are rendered meaningless because they lack context and they lack boldness, or the willingness to call out the things that are actually wrong in our society.

I also think the soul of this country is like every soul. It needs work. It needs healing. It needs nourishment. And it needs to be kept from its natural failings and weaknesses and temptations, the ways in which we as people make the wrong choices or are led down paths that we then find ourselves regretting. I think about my nation in the same way, because I think the soul of America today is restless and weary and in need of healing.

F&L: You’ve said that you post reminder notes of personal mottos for yourself, and you’ve suggested one for the rest of us that says “Justice is calling.” What words of encouragement would you offer to those who find that both inspiring and overwhelming?

DW: Justice is calling in this country, and if you believe in the potential of this nation to deliver on its promise, you must be engaged in the political processes, the political and civic processes, that make it possible for America to exist.

This is no time to be on the sidelines. Whatever your political interest, your political persuasion, religious affiliation, now is not the time to sit on the bench. You’ve got to be on the field. You’ve got to play to win, and to play for the long term.