At a moment last spring when it looked as if negotiations between the United States and Iran might fail, the two nations’ top energy officials had a breakthrough. Ernest J. Moniz, the U.S. Secretary of Energy and a former chair of the physics department at MIT, and Ali Akbar Salehi, the head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran and an MIT alumnus, began sharing memories from their days on the MIT campus.

Moniz presented Salehi with baby gifts bearing the MIT logo for his newborn grandchild. The sweet springs of cooperation began to flow, and progress in the negotiations resumed.

The physicists had discovered an intersection in their lives’ stories, dwelt in it for a graceful moment, then allowed that shared space to nourish possibilities for peace. They recalled having been in the same place, and how that place had shaped both of them. Days later, the framework of an agreement between the United States and Iran was announced.

Remembering a shared story just may tip the balance from hostility to cooperation, perhaps from war to peace.

The recent conflict over the Confederate battle flag betrays the bitter consequences of privileging tribal memory over the comity of the larger community. When I insist upon my people’s memory as the only truthful recounting of the human story, I exclude from my narrative the lives of others whose journeys have been just as authentic as mine, though along different paths. I preclude the possibility of our recalling a shared intersection along the way, and foreclose conversation that could be nurturing, even redemptive.

The Old Testament, in Deuteronomy, anticipates the sad consequences of this isolationism. In its pages, God commands kindness to strangers, to the poor and to slaves, repeating the refrain, “Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out from there” (Deuteronomy 5:15 NRSV; see also 15:15; 24:18, 22).

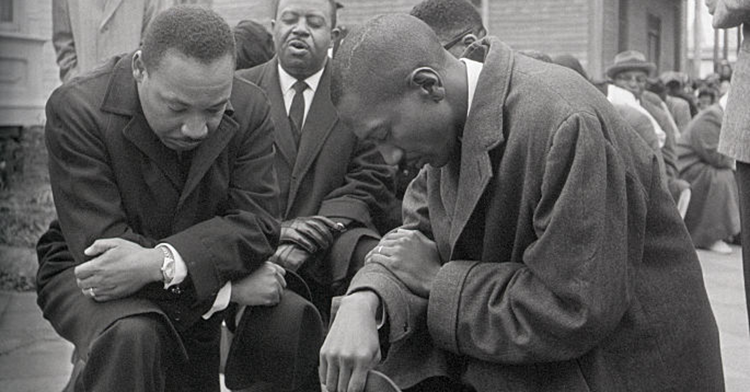

There can be no godly community, suggests the Deuteronomist, without honest remembering. If I recall my own time in slavery, then my life can intersect with the lives of others whose scars from the shackles are fresher than my own. If, just for a moment, I can stand with the more recently enslaved in the sacred space of common, graceful memory, then I can emerge from that place a peacemaker.

I can set aside my battle flag and let the cross suffice as the emblem of our common journey.

In the United Methodist tradition, liturgies for both sacraments encourage deep remembering. “When nothing existed but chaos,” the Thanksgiving in the Baptismal Covenant begins, “you [Lord] swept across the dark waters and brought forth light. In the days of Noah you saved those on the ark through water. … In the fullness of time you sent Jesus, nurtured in the water of a womb.”

When the Eucharist is celebrated, the bread and cup are offered after the creative and redemptive work of God is recounted, from humanity’s being formed in God’s image through the finished work of Christ on the cross. The bread and wine, the congregation recalls, is in sacred continuity with the loaf and chalice on the table at the Last Supper. The church cannot be sacred community, these liturgies affirm, apart from cherished, nurtured remembering.

Perhaps the sin of forgetfulness lies at the root of much of our strife, anger and belligerence. If I forget whence I came, the intersections with my imagined enemies’ narratives are lost, and I live in a landscape of illusion, convinced of the righteousness of my own politics and the sanctity of my own flag.

Cultivating deep remembering as a spiritual practice -- as our sacramental liturgies and the author of Deuteronomy encourage -- may enable “the healing of the nations,” as the writer of Revelation envisioned (Revelation 22:2), as well as the mending of hometown bitterness. “Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt.” Amen.