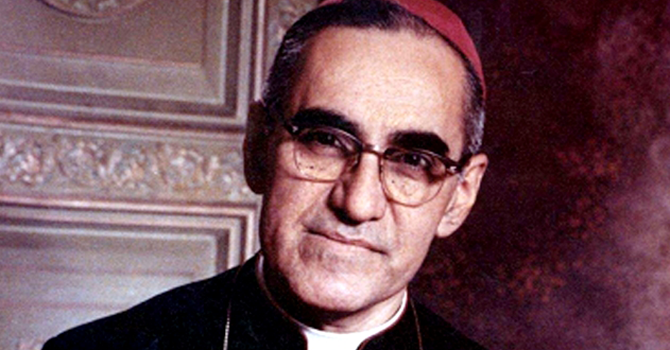

On March 24, 1980, Archbishop Óscar Romero was assassinated at the altar of the chapel of the Hospital of Divine Providence in San Salvador. The text he had just finished preaching on was John 12:24: “Unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit” (NRSV).

That afternoon, he became the grain of wheat. He fell; he died; he bore much fruit. Romero is remembered in many ways: as a shepherd, a martyr, a father of the Latin American church, a saint.

He is also remembered as a theologian -- something that has not been sufficiently appreciated -- which I discuss in my book “Óscar Romero’s Theological Vision: Liberation and the Transfiguration of the Poor.”

But he is perhaps best remembered as a preacher.

Romero’s preaching was an unprecedented social phenomenon in El Salvador. The vast majority of the population tuned in to listen to his homilies, which were carried on the country’s Catholic radio station. It is said that on Sunday mornings, you could walk the streets of any town in El Salvador without missing a word of his sermons, because every home radio was tuned in to the live broadcast.

Soon after Romero became archbishop of San Salvador in 1977, his friend the Rev. Rutilio Grande was killed. In the homily Romero preached for the funeral, he spoke of the love that moved Grande to serve and defend the poor people of his parish.

Aware that the perpetrators of the crime might be listening to the radio broadcast, Romero addressed them directly: “Brother criminals, we love you, and we ask God to pour forth repentance into your hearts.”

Romero’s phrase “brother criminals” beautifully holds in tension the preacher’s desire to both speak prophetic words and offer a pastoral response. The killers are brothers because they are, in all likelihood, baptized. They are criminals because they have shed innocent blood. Romero speaks truth to power in love, in hopes that the perpetrators might be moved by the same love.

To me, the one word that sums up the content of Romero’s preaching is truth. It is because he preached the truth that people flocked to the cathedral in unheard-of numbers and enthusiastically listened to sermons pushing the two-hour mark. In one homily, Romero told his listeners that two days earlier, while claiming his briefcase in the customs area of the airport, he’d heard someone say of him, “There goes the truth!” The words filled him with optimism for his bold message, he said, for indeed he did not carry “contraband or lies”; rather, “I carried the truth.”

It is because his yes was yes and his no was no that the government forces considered his voice a threat. They jammed the radio broadcasts of his homilies and blew up transmission towers. And when all of that failed, they killed him.

Romero used his voice to speak the truth and defend the most basic and beautiful of God’s gifts: life. A sample of titles from his homilies reveals his strategy: “Christ, Life and Treasure for All”; “The Divine Savior, Bread of Life”; “The Divine Savior, Life of the World”; “The Divine Savior, Word of Eternal Life.”

The pattern is clear. The true answer to the great social questions in El Salvador is found in Christ. Jesus is the savior of the world because Jesus is the author of life.

Romero affirms that the glory of God is a poor person fully alive -- Gloria Dei, vivens pauper. Thus, the greatness of a nation is measured by the life of its poor.

Romero has been called the voice of the voiceless. Certainly, he spoke in behalf of the outcast in his archdiocese. In a typical Sunday homily, Romero would devote about half his time to a detailed description of the atrocities taking place in El Salvador during the week.

Particularly striking is how he called the victims by name. In Romero’s preaching, those who had been rendered voiceless through intimidation or death found a voice. As long as their names were remembered, they would not be erased from history.

Even so, Romero himself never claimed to be the voice of the voiceless. Romero believed that the whole church is called to be the voice of the voiceless, because, as he told his listeners, the church is “God’s best microphone.”

This is an unbelievable claim, contradicted by the history of how the church has often served to amplify the voices of the powerful.

And yet Romero insisted that the church is God’s best microphone, because it is the body of Christ in history. In carrying out its mission, the church listens to the voice of Christ in Scripture and in the cries of the marginalized people longing for liberation. The church is God’s best microphone when kept close to the lips and lives of the poor.

As I think of the 40 years since Romero was killed, I think of what has been happening in El Salvador. It has been a Lenten journey for Romero’s people. Peace accords have been signed; monuments have been built; but not much has changed.

For the past 10 years, I have been traveling to El Salvador regularly. Just recently, I was there on a pilgrimage with Duke Divinity School students. We visited the sites of mass graves, met an ecumenical group of women working for peace, spoke with pastors and heard from human rights lawyers.

The signs are bleak: vast income inequality, a culture of impunity, the criminalization of youth, the erosion of family life, massive migration. Yet I find El Salvador to be a fundamentally hopeful place, because God’s best microphone is still broadcasting.

Rutilio Grande is gone. Óscar Romero is gone. But as Romero said in an Advent homily, “The Word remains and this is a great comfort to all preachers -- their voice will disappear but their words which are a proclamation of Christ, will remain in the hearts of those who desire to accept them.”

The Word remains, and it is still being carried by God’s best microphone, the people of God, the church, Christ’s body in history.