Edgar Luis Gallegos Campos hunched over one of the many colorful postcards on his table. His brow furrowed in concentration, he focused on writing a message to someone in an immigrant detention center.

Campos didn’t know the person he was writing to, but the act of reaching out to someone in detention is close to his heart. He has a brother in Mexico who’s incarcerated.

“I’m telling him to have faith in God, patience and hope,” Campos said. “At the end of the day, God is the only judge, and he can help us if we let him.”

Around him, a couple of hundred strangers began to fill the tables inside the event space of First Presbyterian Church in Greensboro, North Carolina. At this early-November gathering, they would share a Thanksgiving meal of homemade dishes contributed by community members from all over the world.

The event is hosted annually by FaithAction International House, a faith-based nonprofit that supports and advocates for immigrants and refugees.

FaithAction has many partners and many projects, but at the core of its work is the four-step Stranger to Neighbor model, a program designed to challenge the stereotypes of immigrants and foster trust between a community’s longtime citizens and its newcomers.

FaithAction also serves institutions like congregations and local governments, with trainings on immigration trends and how to build trust with the newest members of a community. The trainings reach as far as Florida and Oregon, and with a recent grant, FaithAction plans to expand its programs to other countries.

In the Stranger to Neighbor model, two communities are invited to risk opening up their lives to change and shared action. How are both groups challenged to grow through this process?

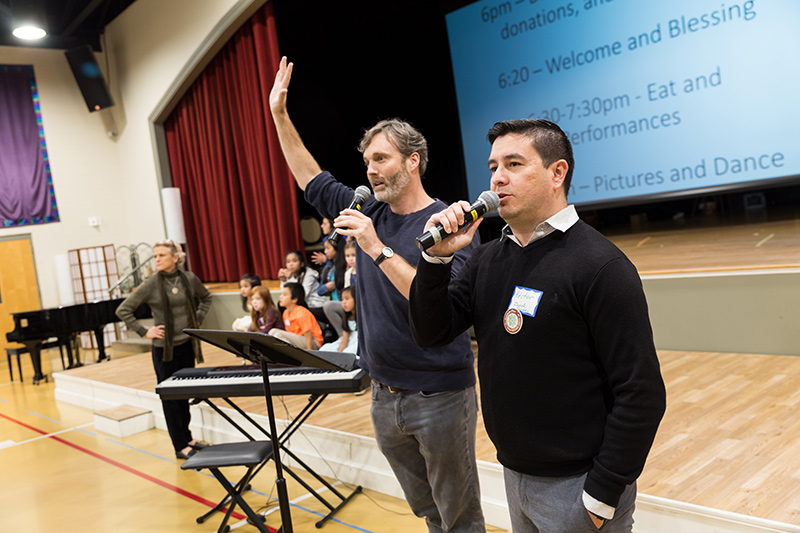

“Every day, there are people who ring our doorbell who are facing significant challenges,” said the Rev. David Fraccaro, the nonprofit’s executive director.

“It’s a storm outside. [At FaithAction] they can be received by immigrants themselves, who know how to empathize, who have been in their shoes, who see them as people, not as a problem, and who treat them with tremendous dignity.”

The multicultural Thanksgiving meal and the postcard-writing project are embodied examples of the Stranger to Neighbor approach.

Campos, who is originally from Mexico, came to the event with FaithAction board member Hector Gomez, who was his teacher in a free English-instruction program for adult learners sponsored by the University of North Carolina Greensboro.

The postcards were delivered to people in immigration detention centers during the winter holidays -- a gesture organized by a local interfaith council, one of FaithAction’s partners.

The power of unlikely friendships

Fraccaro developed the Stranger to Neighbor program out of his own life experience, in a small, conservative, predominantly white town in Indiana, where he grew up, and later in Queens, New York, one of the most diverse urban areas in the world, where he worked as an actor.

In Queens, as he gradually became comfortable with -- and then appreciative of -- the rich diversity of his neighbors, his path and vocation began to shift.

After witnessing the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and seeing their profound effect on the community’s perception of “strangers,” Fraccaro decided to leave acting behind and enroll in Union Theological Seminary for a master of divinity degree and then Columbia University for a degree in human rights.

And for eight years, he visited noncriminal immigrants held in nearby detention centers as The Riverside Church’s coordinator for the Sojourners Immigration Detention Center Visitor Program, one of the country’s first volunteer programs of its kind.

Where have you encountered suffering? What new vocation directions are calling out to you from those experiences?

There, as he made friendships with people from all over the world, he began to consider how trust and cooperation could develop between native-born citizens and newcomers who arrive from different cultures, faiths and countries.

Learning about immigrants’ lives -- about the challenges embedded in the nation’s complex immigration system and the courage required of those stuck in a prolonged in-between existence -- Fraccaro recognized that he was needed in a place similar to his hometown: a small city that was experiencing rapid demographic changes. In 2011, he began his work with FaithAction in Greensboro.

“I happen to be an ordained Christian minister today because of my Tibetan Buddhist, West African Muslim and Catholic Colombian friends inside of the detention center who helped change my life. A lot of what I do today is in tribute to them,” he said.

Moving from ‘stranger’ to ‘neighbor’

FaithAction began operating in the mid-1990s in response to North Carolina’s rapid growth of refugee and immigrant populations. Between 1990 and 2000, the state’s immigrant population grew by more than 250%. Immigrants now make up about 10% of the population in Guilford County, where Greensboro is located.

How are you paying attention to changes in your community? Who are potential partners with whom you could explore the Stranger to Neighbor model?

Today, FaithAction operates out of a white two-story house across the street from First Presbyterian Church and serves more than 3,000 immigrants and refugees from 60 countries each year with subsidized legal assistance, food drives, housing assistance, and education and employment readiness opportunities.

With a three-person staff and a group of volunteers, the nonprofit has recently operated with a $350,000 budget. Its main source of funding is donations from individuals and congregations, but it also relies on local, national and international grants. It most recently received a grant from OpenIDEO that increased its budget by more than 50%.

FaithAction advocates for and serves people from all over the world. About 75% of its clients are of Latino heritage, and the remaining 25% are from West and Central Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and Europe.

Faith Action among 2019 winners

Leadership Education at Duke Divinity recognizes institutions that act creatively in the face of challenges while remaining faithful to their mission and convictions. Winners receive $10,000 to continue their work.

The organization is not affiliated with any particular religion; rather, it encourages the shared values of many faiths and the dignity of all human beings -- and that is the basis of Stranger to Neighbor. FaithAction is not just about helping those in need but also about bringing together separate and sometimes polarized worlds.

Stranger to Neighbor grew out of a faith-based community, but it’s a social model that has been used in higher education and, indirectly, by law enforcement, health agencies and local governments through FaithAction’s various programs and trainings, Fraccaro said.

Each year, FaithAction does more than 70 Stranger to Neighbor trainings, which began in 2011. The model features four steps:

- Education: Participants learn about their neighbors and are challenged to deepen their perspectives and question prejudices about both immigrants and Americans.

- Exchange: Participants spend time together building relationships and learning how to trust each other. They identify shared values and concerns and think of ways to solve community issues.

- Community action: Participants commit to and implement an action that addresses or solves a community issue.

- Storytelling: Participants share with the community the story of what they learned and experienced together so that the narrative of cooperation rather than conflict takes root in the community culture.

Fraccaro sees FaithAction taking the “exchange” step in the multicultural Thanksgiving, where hundreds of Greensboro residents, U.S.-born and immigrant, come together to enjoy a few hours getting to know one another.

“It makes the slogan real. It’s not just an intention; it’s a model for change. It helps us fulfill our mission,” Fraccaro said.

Another example of the model is the program for which the organization is best known, the FaithAction ID.

This program provides a verifiable form of identification to anyone, including immigrants, refugees and homeless individuals, who does not have access to government-issued identification. The community ID program has spread beyond Greensboro to 24 other communities in North Carolina and six other states.

The program took shape after six months of meetings, facilitated by FaithAction, between the police and the immigrant community in Greensboro.

The process of getting and retaining the ID, which must be renewed each year, involves ongoing dialogue with law enforcement officers, with whom immigrants might not otherwise willingly interact.

“We may call it the FaithAction ID program, but it’s all the Stranger to Neighbor model,” Fraccaro said.

‘Oh, yes. That is our experience.’

In 2014, Guilford College Spanish professor Karen Spira was new to Greensboro when a colleague recommended that she work with Fraccaro and FaithAction to develop a project with her students and a predominantly Hispanic immigrant community located on the outskirts of the city.

For four years, Spira employed the Stranger to Neighbor training and variations of it in her intermediate Spanish classes. Each time, it yielded a threefold success: the students and immigrants got to practice their language skills, listen to each other’s concerns and build meaningful relationships.

Each semester, Fraccaro did a presentation to help the students think critically about immigration in the public discourse and how immigrants’ narratives are framed -- the education step.

The first semester Spira used the model, the group considered the lack of access to driver’s licenses for immigrants in North Carolina through a series of potlucks and conversations in the Hispanic neighborhood’s meeting space.

The immigrants spoke about the difficulty of living in a rural area without a driver’s license, Spira said, and the students shared their experiences of life in an American college. This was the exchange step.

What in the steps of education, exchange, action and storytelling is most inviting or urgent for you in your context?

“I remember a student one night was talking with this very outspoken woman who was always really engaged in conversation when I was doing this project in the community,” Spira said.

“And I remember that the student wrote in her reflection -- the students had to do written reflections after each visit -- that this woman talked to her as if she was her daughter, like, she looked her straight in the eye and [gave] her life advice, and that that was a really special moment where she felt the relationship shifted.”

When it was time for the action step, the group came to a unanimous decision that the students should write opinion pieces about the lack of access to licenses for undocumented immigrants.

Spira challenged the students to a writing contest. She chose the three best pieces and had the writers present them to the group for a final selection.

The group decided that the piece by student Chloe Williams got to the heart of what they felt.

This is how Williams ended it:

Besides the risk to others, when an undocumented immigrant decides to drive without a license, he or she is also taking a very large personal risk.

If a police officer stops him or her, he or she can receive a ticket, or possibly be sent to court and therefore be in danger of deportation. People can be deported just because they need to drive. Is it fair for someone to risk this just to go to the store or to work? What if you had to be afraid every time you left your house? How would your life be, if you could not drive?

Spira attempted to publish Williams’ editorial in the local newspaper -- the storytelling step -- but that didn’t pan out. Regardless, the potlucks brought together the moms and children of the neighborhood with her students, and that was powerful, Spira said.

“Everybody was cooking all of this beautiful food from different cultures. My students, who barely have access to kitchens -- a lot of them live in dorms -- were finding ways to cook. I was cooking. It was a big effort. It enabled us to have these wonderful dinners where we sat down together,” she said.

How does the storytelling step relate to Christian mission work today? What are some benefits of telling stories in your context?

“I remember that the response was -- when Chloe read hers -- was, ‘Oh, yes. That is our experience.’ I think they thought that she got at what was most challenging about not having a driver’s license. At that point, it was all women. These were all moms who were dealing with all of the things they were trying to do for their children,” Spira said.

Building multifaith and multicultural bonds

Spira saw so much success with Stranger to Neighbor in her classroom that when her Jewish congregation at Temple Emanuel in Greensboro began to ask how they could advocate for and be in solidarity with immigrants, she decided to introduce it to them.

These questions emerged right after January 2017, when President Donald Trump had issued multiple executive orders that affected thousands of immigrants and refugees.

Spira calls it her most ambitious Stranger to Neighbor project to date, because it involves a long-term commitment from congregants of two separate religious institutions.

Temple Emanuel searched for about a year for another religious institution with which to commit to doing the work. They found Daystar Church, a church with a large Spanish-speaking congregation.

For more than a year now, each congregation has hosted the other for meals and conversations. For the first gathering, Temple Emanuel hosted Daystar Church during Sukkot, a Jewish festival that emphasizes welcoming the stranger. In a grassy area of the temple’s campus on a fall day, they celebrated together, teaching each other songs in Hebrew and Spanish.

The second time they met, Daystar hosted at the church. It was the same day as the Tree of Life mass shooting in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where a man opened fire during morning services, killing 11 people and wounding six.

“It was very meaningful for us as Jews that this other community really cared about that, to [ask], ‘Is this something that happens in the U.S.?’ [We told them], ‘No, actually, this is something completely unprecedented in the U.S.,’” Spira said.

Gomez, the FaithAction board member, is also a member of Daystar Church. He said the group has written letters to members of the state General Assembly, both requesting that sheriffs’ offices not participate with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and advocating for in-state tuition for DACA students.

“We’ve formed beautiful relationships with people who you would perhaps see in a different church or different congregation [and] you’d say, ‘I’m not going to talk to that person. He is Jewish and I’m Christian,’” Gomez said.

Serving others

At the Thanksgiving dinner, the UNC Greensboro student dance company Corazón Folklórico entertained guests with lively music and swirling skirts.

The company was just one of the evening’s featured performers, which also included the Triad Tapestry Children’s Chorus and an R&B/reggae singer.

Angel Herrera, a dance instructor for the Corazón group, attended the dinner with his parents and wife.

Many of the Corazón students were born in the U.S., he said, and he enjoys teaching them something that he’s proud of.

Herrera has been a regular part of FaithAction events since 2011, he said, because he appreciates the organization’s dedication to serve all people.

“I love to help people,” Herrera said. “And if I’m ever in a situation where I’m stuck and need help, I would like for someone to help me.

“It doesn’t cost you anything to serve. All that time you spend watching TV you could dedicate to helping people.”

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- In the Stranger to Neighbor model, two communities are invited to risk opening up their lives to change and shared action. How are both groups challenged to grow through this process?

- Fraccaro developed the Stranger to Neighbor model after visiting noncriminal immigrant detainees in New York. Where have you encountered suffering? What new vocation directions are calling out to you from those experiences?

- FaithAction leaders paid attention to the growing immigrant population in their community and developed a model for action rooted in hospitality and relationship building. How are you paying attention to changes in your community? Who are potential partners with whom you could explore the Stranger to Neighbor model?

- What in the steps of education, exchange, action and storytelling is most inviting or urgent for you in your context?

- Fraccaro explains that the model’s fourth step -- storytelling -- helps people move from conflict to cooperation. How does this relate to Christian mission work today? What are some benefits of telling stories in your context?