I sat in my bedroom, which offered the quiet and privacy needed to speak on the phone with an elderly bereaved widow whose only son had just died. Her voice cracked as she tried to keep her composure while narrating how he would send her flowers “just because” — no occasion necessary.

She recounted how he had demonstrated his love for her through so many kind deeds, and how he had filled the void of loneliness left by her late husband’s death. When she broke down and sobbed, I practiced deep listening techniques I had learned during my training as a “death doula.”

I was focused, and I rehearsed bringing my attention back to the conversation whenever my mind wandered. I was distracted by “How do I fix this?” Yet I knew from my training that this was not my role, so I redirected my attention to just being present.

The intent of death doulas is not to fix anything. Instead, their purpose is to listen and accompany.

While the word “doula” (Greek for “one who serves”) is usually associated with birth, assistance with the transition to death has been in increased demand over the past few years, especially as more and more people express a desire to die at home. The death doula approach is based on the birth doula model.

Some death doulas — also called end-of-life doulas, death midwives, death coaches and end-of-life coaches — are hospital chaplains; others are nurses or hospice volunteers. Many of them are people like me, who feel called to serve individuals in the transition to death, as well as the loved ones left behind in the process of grief.

Doulas provide emotional support for the dying person and physical assistance to caregivers, and they advocate for the dying person’s wishes.

Months before the world went into lockdown, I decided to invest in training as a death doula with the International End-of-Life Doula Association. It was a way to deepen my skills as a trained volunteer spiritual caregiver with Somerville-Cambridge Elder Services in Somerville, Massachusetts.

It took on new meaning in March 2020. I felt unprepared to serve families during the pandemic — I’d assumed I would be physically present with those who were dying. Whether volunteering as a spiritual caregiver or as a doula, I prefer being in person. Suddenly, I had to care for those transitioning and grieving during quarantine restrictions.

Within my Black church tradition, I found resources that helped get me through being a doula in the less-than-ideal circumstances dictated by the pandemic.

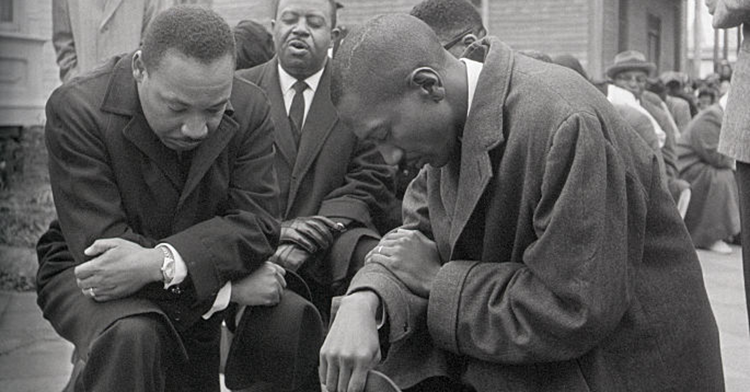

In my tradition, we refer to deep compassionate accompaniment as “tarrying.” To tarry, in this sense, means to linger — to be still and give full attention to God in anticipation of the move of the Spirit. In this tradition, it is simply part of life to “sit with folks” who are dying and grieving.

The expectation of the move of the Spirit is not always one of ecstatic jubilation, which is commonly the culmination of worship. Rather, the Spirit comes during calmer moments of communal lament, and even moments of sitting with one another and God in reverent stillness. What is most essential in tarrying is listening.

For example, during my childhood, a beloved church member was dying from AIDS. My father, who was a deacon, would go with other church members to sit with him as he was dying. One lady would sometimes rub his feet while they tarried with him. He died knowing that he was loved and cared for because of a few folks who took the time to tarry.

As a death doula during the pandemic, I found myself having to learn what it could look like to sit with folks, not in person, but over the phone.

A middle-aged woman who lost her brother and mother within the same year said to me, “Those of us who are grieving during the pandemic can’t get what we need — the hugs, the care.”

Though I was not able to hug, I could listen.

Speaking with her during the lockdown was difficult. I felt powerless hearing her weep and sensing the pain and loneliness in her voice. She had stopped working, attending church and doing other things that had once brought her joy and fulfillment.

After walking with her through this dark time, I was gratified later to listen to her talk about getting back to work and attending church again as she slowly came out of the initial phase of grief.

The pandemic helped me see how listening — even on the phone — can be a clear expression of love and a generative space for hope to flourish. Through this sitting with others, one not only performs the ministry of presence but also connects with others as a witness to their suffering.

This experience has forever changed me. I understand differently my role as one who accompanies others on their life/death journey. The pandemic has changed and continues to change all of us, especially Christian leaders, who are called to compassionate accompaniment within a faith community.

How are Christian leaders to manage overwhelming grief — their own and that of others?

As faith leaders, we provide healing for others, but we must also replenish our own spirits. Prayer, lament and fellowship are traditional Christian practices that can support our efforts to accompany pandemic-stricken individuals while on our own quest for healing and wholeness. We also need rest, care and Sabbath.

And I believe that faith leaders ourselves can benefit from tarrying, from someone sitting and listening to us and our challenges of ministering to a grieving world, from someone listening to our stories.

I have a few women ministers who accompany me; they have tarried with me through grief and disappointments. Their compassionate listening and ministry of presence are generative and model what it means to be faithful ministers during this difficult time.

As we accompany others while managing the overwhelming grief that characterizes this moment in history, faith leaders can draw on practical forms of healing. Both giving and receiving deep listening and tarrying can feed our spirits enough to enable us to continue the work that so many people need right now.

Through this sitting with others, one not only performs the ministry of presence but also connects with others as a witness to their suffering.