As an old man, the poet T.S. Eliot said of his craft:

Words strain,

Crack and sometimes break, under the burden,

Under the tension, slip, slide, perish,

Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place,

Will not stay still. Shrieking voices

Scolding, mocking, or merely chattering,

Always assail them.

These lines from Eliot’s “Four Quartets” come to mind when I reflect on the connection between the creation of The Saint John’s Bible and the kind of imagination needed for ministry -- the kind of imagination that trades in words and images and stories, that moves from world to text and back again, that looks to the past, speaks to the present and hopes for the future.

For some veteran pastors, the opposite of Eliot’s sentiment may feel more like the truth. The words of Scripture comfort, like an old friend known over a lifetime’s worth of pattern and habit and love. But with familiarity may also come a loss of luster; the words move, but with predictability. They saunter instead of dance, soothe more than surprise. The lack of strangeness to their sound stirs a fear: “Is there anything new to say that I haven’t preached already?”

Or, for some young ministers -- fresh out of seminary, full of exegetical technique, dizzied by hermeneutical perspectives and bloated with historical considerations -- another danger awaits. Interpretive friends can turn into homiletical enemies, “shrieking voices” that shout over the text: “How can this be a word for this time and place? A word for this congregation?”

Imaginations, either by time or by technique, can narrow. What opens them up, oddly, is more imagination.

Art has a dialectic relationship to imagination. It is both a product of imagination and what sparks it. Every morning Karl Barth put on Mozart before he wrote. I’ve heard of pastors writing sermons in art galleries. A friend plays John Coltrane and has what he calls “writing jam sessions.” How many books are written because others were first read? Imagination creates art, but art sparks imagination.

Andy Crouch puts this in a different, more compelling way: cultural goods (or artifacts) not only cradle and carry cultural traditions over time but also generate them. Cultural goods produce more culture.

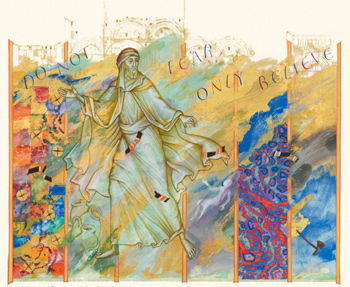

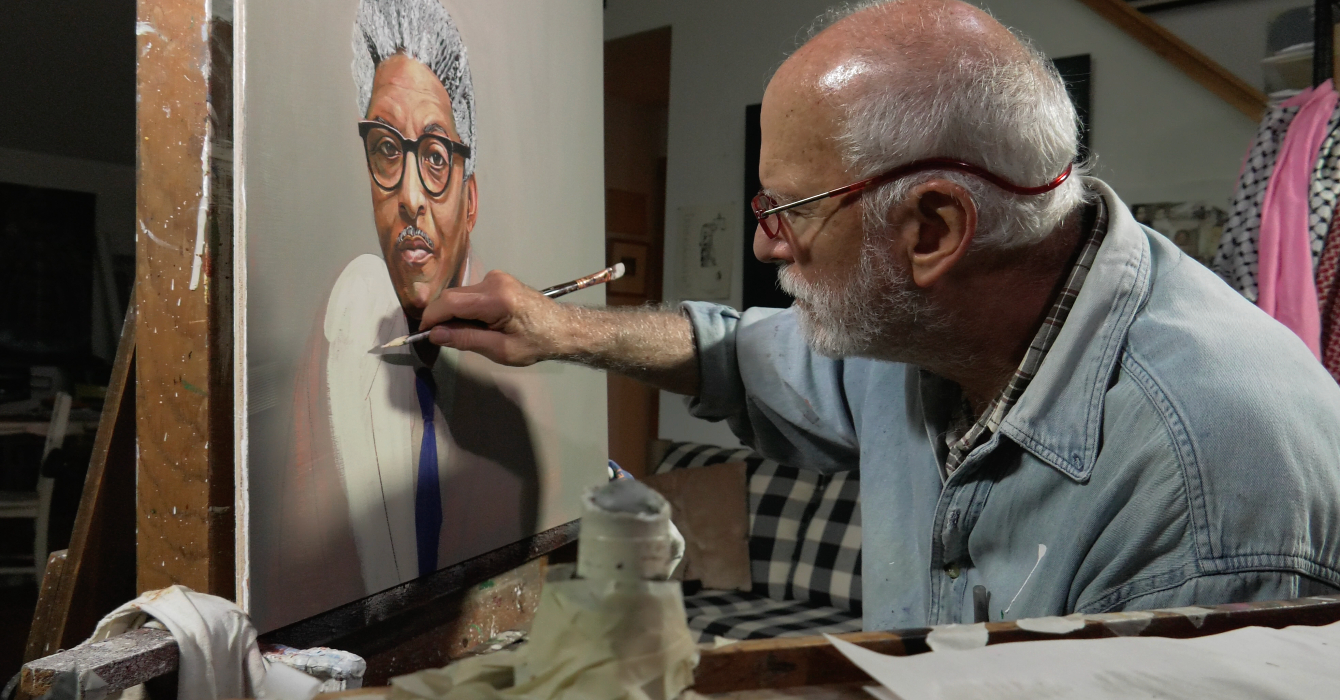

This is what makes The Saint John’s Bible captivating. As a work of manuscript illumination -- book painting that uses radiant colors and precious metals -- it is the product of a medieval tradition practiced by the Benedictines for centuries and combines historical craftsmanship with new artistic sensibilities. It is both the product of a cultural tradition and a cultural product that creates more culture.

How? How does it create more culture or spark more imagination?

As a work of art, the illuminated Bible bears a doxological end. Its creation is an act of worship, a meditation in and through Scripture. But it also generates more imagination for ministry in the way the school uses the illuminations.

Saint John’s School of Theology-Seminary designs programs for lifelong learning and ministry around the illuminated texts. They host “Praying with Imagination” retreats for pastors and offer Seeing the Word, a program that guides reflection on Scripture by using the Bible’s illuminations.

They’ve adapted the practice of lectio divina -- meditation on Scripture -- to visio divina, a similar practice that incorporates both word and art. Pastors reflect on the illuminations and make their own books as an act of spiritual and theological reflection. Catholic school students have done the same.

If in some sense ministry is an art form, then the illuminated Bible is a work of art that creates more art, a product of imagination that fuels more of itself.

These programs and their use of the illuminated Bible connect with Saint John’s Sustaining Pastoral Excellence project and reflect what 10 years of the Sustaining Pastoral Excellence program has taught about supporting clergy: Christian ministry is beautiful, but pastors need space in their lives to remember this, to seek spiritual renewal and to refresh their imaginations for ministry.

The act of meditating on Scripture through art beckons pastors to consider anew the beauty of the Christian life and ministry, to marvel at the wondrous calling placed on their lives. The Saint John’s Bible provides an imaginative space into which pastors can gaze, once again, at the mystery of the story of God’s life among us, and sense that the world can, as Marilynne Robinson writes, “shine like transfiguration.”