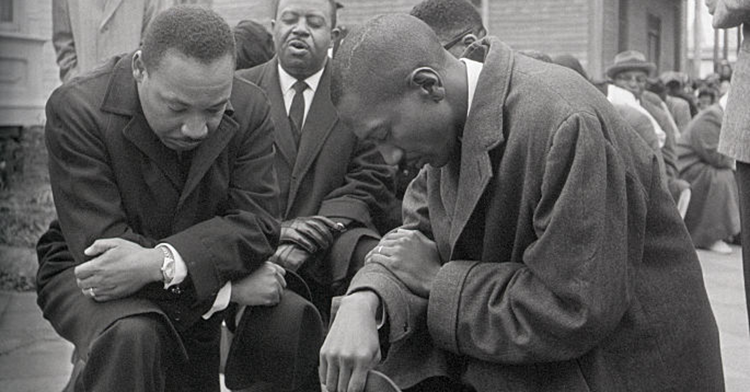

On May 10, 2016, the Rev. Laura Jaquith Bartlett stood before the delegates, bishops, staff and audience of General Conference -- the quadrennial gathering of the global United Methodist Church.

It had just begun, and almost 3,000 people from around the world filled the exhibit hall of the Oregon Convention Center, prepared for 10 long days of difficult work.

But first on the agenda was opening worship. Bartlett, worship leader for General Conference, stood at the podium and offered the delegates, bishops, and others a gift: a set of prayer beads.

“We will use them in our worship throughout these days together,” she said, before the congregation was invited to pray. This was the first of many times the congregation would be invited to pray with beads during the twice-daily worship services.

A number of people picked up the beads with interest; others hesitated. Some moved their fingers from bead to bead; others just held the strands in their fists.

Bartlett’s invitation was the moment I had been waiting for. Twenty-six years ago, my mother returned from a mission trip with a gift: a hand-carved wooden rosary.

It was an odd gift, since we were Presbyterian. Still, I was captivated, and from then on, I was a collector of Catholic rosaries from around the world. I was fascinated by the fact that people used these common, ordinary beads to connect with God. But I did not pray with them. The rosaries merely hung on my wall.

That changed in 2009 when I learned about the Anglican rosary, a new format of prayer beads for Protestants. Suddenly, I was more than just a collector; I began researching the history and use of prayer beads, writing and teaching about them, making and selling them.

Most importantly, I began using them, discovering a spiritual life that was deeper than I had ever thought possible.

Two weeks before Christmas in 2015, I received a call from Tom Albin, co-chair of the prayer ministry team of the General Conference 2016 and the dean of The Upper Room Chapel.

The UMC Council of Bishops had decided to distribute prayer beads at General Conference, he told me. Would I be willing to help coordinate the making of more than 2,000 sets of prayer beads?

Absolutely, I thought. As far as I could tell, this would be the first time a large, representative gathering of Protestants would be taking up beads in prayer. It would be historic.

The bishops had decided to distribute prayer beads at the gathering as a way to promote unity. It was no secret that the conference was going to be contentious.

Like most other denominations, the United Methodist Church was confronting the issue of human sexuality. In the months and years preceding the gathering, people on all sides of the issue had been organizing support, building caucuses and preparing for a monumental debate. It was clear that this conference would be difficult, even painful. There were rumors of an impending split.

Recognizing this, the bishops declared the need to infuse the event with prayer for unity and discernment like never before. In partnership with The Upper Room, the council decided to offer, among a variety of initiatives, a prayer strand to each attendee.

Though they understood that the practice of praying with beads would be new -- even questionable -- for some participants, they believed that the beads would signify the participants’ connection to God and to each other.

As Bishop Debra Wallace-Padgett and Bishop Al Gwinn wrote in “Prayer Resources for the Bishop’s Prayer Initiative: 131 Days,” the council offered the prayer beads “as a physical reminder” that people around the world would be praying for and with each person at the conference.

Pat Luna, a delegate from Florida, said the days of the conference were some of the hardest of her life. Luna was not new to praying with beads, but she said she discovered new significance for the practice during the proceedings.

“Time after time, when I felt discouraged and alone and wanted to give up, I would reach for the prayer beads and pray,” she said.

“This tactile reminder kept me focused and reminded me that I was not alone; God was with me, and I was part of the great cloud of witnesses seeking to fulfill God’s will. It was then that I thanked God for this ancient tool that enabled me -- and others -- to draw closer to God,” she said.

Praying with beads or other objects is hardly a new phenomenon; for Christians, the practice dates back to the early church when the first monastics used pebbles or knotted rope to stay focused as they prayed the Psalter each day.

Later, strings of beads were used to help laypeople -- most of whom were illiterate -- count 150 recitations of the Lord’s Prayer, a practice developed in place of reading or memorizing the Psalms. (As a result, the rosary was often known as “the poor man’s Psalter.”)

Beads, then, have a rich history as an aid for people of faith -- a tool to help them focus their minds in prayer, engage in worship, experience a tangible reminder of God’s presence, and quiet their minds so they can listen to God’s still, small voice in their lives.

Yet for too long, Protestants have missed out on these benefits, relegating prayer beads -- as I did -- to Catholics, Buddhists or people of other faiths.

We thought they were taboo. We hadn’t been raised to use beads in prayer, and neither had our parents or grandparents, or the generations before them. We didn’t know why, but surely there was a good reason. And so we kept our distance.

But in the 1980s, a small group of Episcopalians spent time learning about ancient prayer practices, and by the end of their study, they had created a new prayer bead format -- the one I first learned about in 2009.

Unlike the traditional rosary, the “Anglican rosary,” as they called it, was made up of four sets of seven beads. And unlike the original rosary’s set formula of prayers to be used with each bead, the new rosary was free-form in its use.

Still, given the religious climate of the 1980s and, perhaps more to the point, the lack of a vehicle like the internet to spread the word, a version of prayer beads for Protestants was an idea before its time.

Today, however, our seminaries offer courses on spiritual formation and teach centering and breath prayers. Churches have labyrinths and yoga classes. These and other practices, many of which are discussed on websites such as Dorothy Bass’ Practicing Our Faith, and in podcasts such as Krista Tippett’s On Being, are finding more and more adherents.

People are open to -- and even seeking -- ways to incorporate longtime Christian rituals into contemporary spirituality.

And so they are taking up prayer beads. Moving their fingers over the beads one by one, they pray for various family members or list things for which they are thankful. They hold the strands as they go in for chemotherapy or sit in divorce court, remembering that God is as close to them as the beads in their hands.

Bead by bead, they take deep breaths or repeat short prayers as a way of emptying their minds, calming their anxieties and connecting with the God who is constantly whispering words of deep love into their ears. They are praying.

This is not to say the use of Protestant prayer beads is widespread. That’s why I think the decision to distribute beads at General Conference was so significant.

Did the prayer beads solve every problem at General Conference? Certainly not.

Still, many delegates, bishops and other attendees took those prayer strands back home. They showed the beads and told stories of how they had used them in worship. They demonstrated how to pray with the beads. They shared some of the history they had learned. And they began their own dialogues about prayer.

It was a start, and that’s what counts. Because introducing new (ancient) prayer practices takes time. You have to take it step by step, bead by bead.