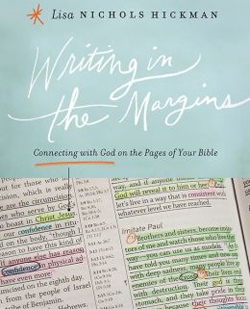

I think that few spiritual practices are as immediate and engaged with Scripture as writing in the margins of the Bible -- an act of connecting with and responding to God.

Just an inch, on either side of the pages, is all that separates word from world. That margin acts as bridge from the text of God’s word in Scripture to the context of this world. It is sacred space.

I discovered the practice through Rich Gordon, a gentleman from our congregation in New Wilmington who served on the Mission Committee and was a leader in our local business community. Although I’ve always been a margin writer, my scribbling did not compare to Rich’s.

After his death from a brain tumor, his family asked me to take a look through his Bible to prepare the funeral service. I discovered a visual record of his days, and of his life with God. Turning those pages was one of my most humbling moments of ministry, and it inspired me to write a book encouraging others to explore this practice.

The practice of margin writing provides a training ground, a learning forum and a prayer garden. I’d like to share some stories of margin writers and the lessons they can teach us.

For Rich, marginalia served as compass, conscience and channel. It was his way of accepting the invitation of 1 Thessalonians 5:17 to “pray without ceasing.” As he grew more ill, his marginalia included prayers for healing, as well as prayers of release and acceptance. On one page, barely visible, is written “True surrender.”

I keep a page of Rich’s Bible at hand -- a reminder to me to pray without ceasing.

Not all marginalia consist of words, however. By opening his Bible and setting a large canvas next to it, artist Makoto Fujimura has made the canvas an extension of the margin.

Using ancient Japanese painting techniques, Fujimura has created abstract images to illuminate portions of the King James Bible. In this video, one can see the delicate Japanese brush sweeping across the text and into the white space beyond it.

Fujimura kindles a habit that is larger than art. I wonder what it would look like for me to place the margin of the Bible alongside the “canvas” of my daily work and play.

This practice has a long history. Bach, Barth -- even Elvis -- along with ordinary saints have all recorded their thoughts directly in their Bibles.

Abraham Lincoln’s Bible has just one bit of marginalia: a thumbprint. This curious testament to marginalia speaks much of the courage and perseverance required by an exceptional leader.

Next to Psalm 34:4 -- “I sought the LORD and he answered me. He delivered me from all my fears” (CEB) --there is an indentation clearly showing that Lincoln firmly grasped this text on more than one occasion to let it sink into his bones. That thumbprint was made by pressure, and by faith.

I wonder whether this return, over and over again, to Psalm 34:4 shaped Lincoln’s character over time and provided a fearlessness that allowed him to become one of the nation’s greatest leaders.

And in this digital age, of course, the silky vellum of the page is becoming a thing of the past. One day after a sermon, I saw a college student in our congregation scrolling on her cellphone.

She quickly whispered, “I’m not texting!” Then she showed me the Bible360 app that allows her to take margin notes next to the biblical text. She had been “writing in the margins” all through worship.

The research of Catherine C. Marshall, an expert in the annotation of texts in a digital age, has helped me look at this practice in a new way. Whether on page or screen, reading and annotating shapes us, marks us, molds us, and motivates us to learn and live, looking for the guidance of Scripture.

The desired goal of these scriptural disciplines is transformation; our time working in Scripture to read the text and then reflect in the margins is directed ultimately toward transformative work in the context of this broken world.

Rich Gordon shared this sacred space as well. He prayed there: What do you want me to learn, God? I want to learn something new every day about you, Lord. And his margin notes continue to lead. He asked himself in the margin, What do you want me to do, Lord? and then answered, Make others great.

Fujimura kindles the sacred imagination. Lincoln fought for emancipation. Digital seekers consult and mark virtual texts. These are all people who have found their ground not just in Scripture but in the reflection that emerges in the margins.

I’m grateful to Rich Gordon, and these other margin writers, for leading me in that transformative activity that has now deeply shaped my character and strengthened my ministry. I hope this practice of scriptural discipline will continue to “make others great” in their Christian service as well.