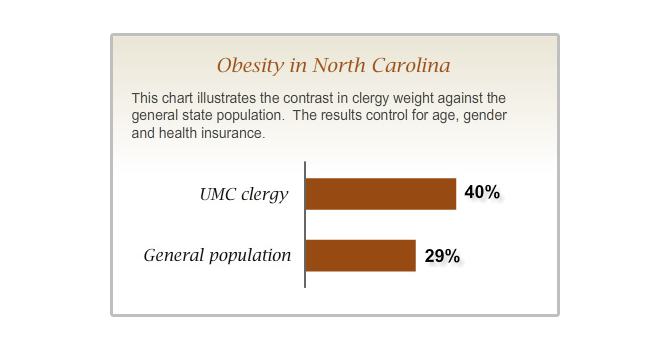

Eleven years ago, researchers with the Duke Clergy Health Initiative set out to assess -- and hopefully to improve -- clergy health.

The multiyear program, funded by The Duke Endowment, sought to assess and improve the health and well-being of United Methodist clergy in North Carolina.

It compared the health of North Carolina UMC clergy with that of people with similar demographic characteristics by means of a longitudinal survey, biometric data, focus groups and interviews, as well as a wellness intervention and behavioral health study called Spirited Life.

The study sounded an alarm about the state of clergy health -- it found that UMC clergy had higher rates of diabetes, arthritis, high blood pressure, angina and asthma than comparable people in the state. It also pointed to higher rates of clergy depression and stress.

But the news wasn’t all discouraging. The Spirited Life intervention helped with some physical problems, and researcher Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell finds hope in it for improving mental health as well.

“The Duke Clergy Health Initiative has been going on for 11 years now, and we spent a lot of the beginning trying to figure out what was going wrong,” Proeschold-Bell said. “We did. But then we really turned, in the last four years, to what’s going right.”

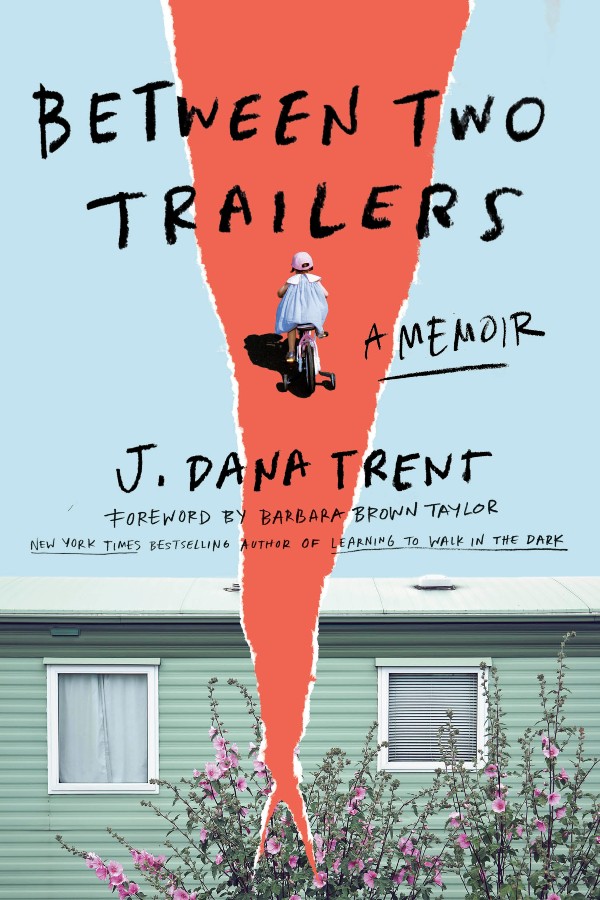

In their book “Faithful and Fractured: Responding to the Clergy Health Crisis,” Proeschold-Bell and co-author Jason Byassee present a summary of the research and intervention for practitioners and offer practical solutions based on the initiative’s findings.

In their book “Faithful and Fractured: Responding to the Clergy Health Crisis,” Proeschold-Bell and co-author Jason Byassee present a summary of the research and intervention for practitioners and offer practical solutions based on the initiative’s findings.

Proeschold-Bell and Byassee spoke to Faith & Leadership about the book and its implications. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: In your book, you write about clergy struggles with depression and stress, but you also say that positive emotions can prevent depression and even some physical illnesses. Can you explain why positive mental health is so helpful -- and how we can achieve this state of mind?

RP: Positive mental health is one of the best-kept secrets [of studies] from maybe the past 15 years, and I think it is now about ready to really come into its own.

RP: Positive mental health is one of the best-kept secrets [of studies] from maybe the past 15 years, and I think it is now about ready to really come into its own.

Positive mental health is feeling positive emotions, having meaning in life, and having social connection and contribution.

So when we think about clergy, for example, we know that they have great meaning in life. They also have great social connection to other people. They feel like they’re making social contributions. Many pastors have this hopefulness that the world can become better -- even if it’s made worse first -- or that individuals can become better.

And all of those are strong aspects of positive mental health.

We’re used to thinking about what’s going wrong, and about symptoms of anxiety and symptoms of depression. But that’s not all of life, you know? What’s also really important are signals when something is going well.

Q: And as you say in the book, these are almost two separate tracks. So both things can be true at the same time, right?

RP: Yes. In a single day, you can feel sad because you found out that, say, a friend lost their job, and you can also feel happy because your child did really well in school.

Q: And Jason, do you find that this segment of “Faithful and Fractured” tracks with what you see and experience as a pastor?

JB: I use in the book the language that was used at John Hope Franklin’s funeral -- that he was a “happy angry man” and an “angry happy man.” Because I think, at best, we pastors can feel both more sorrow and more joy than some of our colleagues in [other fields].

JB: I use in the book the language that was used at John Hope Franklin’s funeral -- that he was a “happy angry man” and an “angry happy man.” Because I think, at best, we pastors can feel both more sorrow and more joy than some of our colleagues in [other fields].

RP: In terms of pastors’ positive emotions and negative emotions over the course of a week, they have a lot of both. They truly are living on both of those continua of lots of positive and lots of negative.

The Duke Clergy Health Initiative has been going on for 11 years now, and we spent a lot of the beginning trying to figure out what was going wrong. We did.

But then we really turned, in the last four years, to what’s going right.

And it’s a part of the picture that you can easily miss, because if you’re looking just at negative emotions, well, they are there. The thing is, you also have to look for the positive emotions, because it turns out that they’re there, too.

Q: And you note that when you looked at the Clergy Health study and intervention overall, you were able to help people make improvements in their physical health, but not so much with depression and stress symptoms. How does that fit in with positive mental health?

RP: Sixty-four percent of all pastors who are United Methodists in North Carolina participated in our two-year intervention called Spirited Life. We were really great with the physical health outcomes, but not with the mental health outcomes.

After much discernment, we realized that what was going wrong was we were trying to figure out which pastors were already depressed and then trying to make them better.

And that might’ve worked for some, but it doesn’t change the overall percentage of pastors who are struggling with depression symptoms or burnout or anything else.

What you have to do, I’ve come to see, is you have to get ahead of it. You have to prevent the depression in the first place. So how do you prevent depression in the first place? Positive mental health is really the perfect way to do that.

If people are having more positive emotions in their lives, good social connections and social functioning, and good individual relationships and psychological functioning in the way of having personal meaning and feeling like they’re growing, that is really the recipe to prevent all kinds of mental health problems.

Q: Jason, as a pastor and knowing a lot of pastors, how do you put into practice the things that Rae Jean is talking about?

JB: Learning from my “greatest generation” parishioners, a lot of them had fought in World War II; a lot of them had been through horrifying things. They spoke about those moments as the most powerful times in their lives.

And so it strikes me that it’s not the case that going through something awful is necessarily negative; in fact, it can be extraordinarily positive if the reason you’re doing it is for the blessing of the world. I mean, these folks fought in World War II to free the world from fascism, and so it’s worth enduring nearly any horror.

It strikes me that in the church, we’ve often forgotten that we’re part of blessing the world and loving all people. So there’s a practice of framing the gospel for the sake of blessing that reframes whatever it is we’re experiencing in ways that dovetail with the positive mental health that Rae Jean is describing.

Q: Do you have recommendations, as a researcher and as a practitioner?

Those who flourish in ministry are intentional about their well-being

Challenges are part of any ministry, yet some clergy thrive despite the inevitable setbacks. New research shows that their keys to success can be boiled down to a few simple strategies available to anyone.

RP: When we compared the diary data of flourishing pastors with that of pastors who were experiencing burnout but weren’t depressed or anxious, four things really stood out, and each has practical implications.

Flourishing pastors focus on working in alignment with God; are proactive and flexible in taking care of their physical and mental health; are intentional about setting boundaries around their work and personal lives; and nourish friendships and mutual relationships.

One thing that stood out is that pastors who are doing well are very intentional about their days. And so if there’s something that’s important to them, say a spiritual devotion or exercise or time with a family member -- all these things that can keep you flourishing -- they have plan A, B and C, because a pastor’s day is unpredictable, and heaven knows that plan A gets disrupted all the time.

JB: I tell a story in the book of my friend Wade showing up at my house early in the morning to go running. I didn’t have a choice to go running, because he was there, right?

That became a way of growing in our friendship and also getting healthier. And then we would also pray for one another, and then it became a ministry at the church; we ran a half-marathon together to raise money for people in poverty in our county, and it was several dozen of us, not just me and Wade.

So I’m struck by places where friendship and ministry and health can come together so that they’re not fractured into separate things that you may or may not get done; it’s all just kind of being alive.

I’m struck by how often pastors meet with people over meals, and that’s no bad thing -- we should do that -- but why don’t we meet with people and take a long walk? Or go running?

RP: And for those who don’t want to walk or run, being in nature. You can go sit in a park, and it will be far better for you than sitting in the office.

Q: Is “positive mental health” just positive thinking?

RP: This is not a tale of, “Oh, just think positive and it will all be OK.” Here’s the science of how it works; it’s the “broaden and build” theory developed by Barbara Fredrickson at [the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill].

When you experience a positive emotion, it literally does something to your brain so you are able to see more. If you’re looking at a computer screen, you see more things on the computer. If you’re given a problem to solve, you generate more ideas, and more creative ideas.

You’re more likely to be social with someone; you’re more likely to hang out and talk to someone you didn’t know, regardless of whether you’re an extrovert or an introvert. You’re more likely to donate money, to donate blood, to sign a petition. And you’re also more likely to consider people who are a little bit different from you as being part of your in-group.

So you are broadened out, and a little bit of extra broadening regularly over time leads to your building up resources.

Talking to more people means you’ve built up more social support. Being a more creative problem solver means you have surpassed more problems successfully. Being a little more open to new ideas means you’ve gone on to learn new things and try new skills.

You have broadened and you have built up a life that makes you more resilient against the hard times.

The confusing but wonderful thing is that you can have both high positive mental health and true mental health struggles at the same time.

Q: Alternatively, do you worry that this could be perceived as a glorification of suffering?

RP: No, you should still try not to suffer.

JB: And yet -- it’s also not a glorification of avoiding suffering, right? In the sense that the point of faith is not to dodge all pain. It’s to, as Rae Jean’s saying, be open, whether suffering or not, whether you’re happy about what you’re facing or not.

The “good news” that I hear in our culture is kind of, “Hey, here’s a way to not suffer.” And that’s good, but it’s not always going to work. So what do you do when it doesn’t work?

Q: Jason, you write about “blue note preaching.” What’s the connection?

JB: People don’t usually come to church because they want to feel worse when they leave, right? And often, churches that attract a lot of people have a reputation for being places that you leave happier than you came in.

But the problem is it can end up meaning we avoid hard realities in our life -- in the gathered people’s life and in the life of the world.

At the heart of the Christian faith is a man who’s tortured to death. And so often, churches that are designed to help you feel better about things don’t spend a lot of time on the cross. Yet if we have anything to say to the world, it’s going to have the cross in it.

“Blue note preaching” -- it’s language from Otis Moss III, at Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago. And it’s his way of talking about the African-American church in particular and its musical genius for taking what’s sorrowful and noticing the way it can be caught up into a joy that it didn’t expect.

The African-American church has never had the luxury of avoiding suffering, and so they have always seen that God enters into suffering and then brings resurrection to birth through it. The good news of the gospel is not avoiding pain; it’s God meeting us in pain and bringing resurrection through it, not despite it.

Q: Could these findings or these ideas affect formation?

JB: There’s been enormous effort in seminaries to talk about spiritual formation over the last two decades or so.

So if you take the great stories of Scripture -- God calling Abraham and Sarah from their home to a new land where they can only depend on God and God’s promise; God raising Jesus from the dead and granting resurrection life to everyone through him -- I think preaching and seminaries are really good at trying to get those stories right in a kind of “let’s study the Scriptures, let’s study the tradition, let’s be clear about how to interpret them” way.

But we’re not as good at helping people see how their own lives are intertwined with those great stories or helping people replay those dramas in their own experience of the world. Genuinely great preaching and spiritual formation does precisely that.

It starts with Abraham and Sarah and eventually folds in even us. And I know why we hesitate to do that, because we’re afraid we’re going to take this big, cosmic story in the Bible and boil it down to “how I can get along with my mother-in-law better,” but that’s not what I’m describing.

I’m describing what faith has always done. It’s inscribed countless unlikely people into a story that’s bigger than they are and redemptive and good news for the world.