For the Rev. Dr. Velda Love, serving as the UCC’s minister for racial justice grows out of being “passionately in love with serving God.”

Love provides resources and training, including the new restorative justice curriculum, Sacred Conversations to End Racism, for the 5,000 congregations in the denomination. She also is the co-host of the podcast “Podcast for a Just World: Sacred Conversations to End Racism.”

“My work is to deconstruct [the] institutional ideology so that it is less colonial in its approach and more open,” she said.

“So that people feel like, ‘I can make space; my voice will be heard; my body will be respected; my dignity will be recognized. I will be seen in this institution, and I don’t have to apologize for being here.’”

Before joining the national UCC staff in 2017, Love served for 16 years as the director of intercultural justice and learning at North Park University in Chicago. She spent nine years at North Park Theological Seminary in Chicago as an adjunct professor and conference speaker.

Love has a master’s degree from North Park Theological Seminary and a doctor of ministry degree from Chicago Theological Seminary.

She spoke with Faith & Leadership while teaching at the Summer Institute for Reconciliation of the Center for Reconciliation at Duke Divinity School.

Q: What are the biggest challenges in working for racial justice in an institutional setting?

I spent 16 years in higher education, and the challenge is that it moves really slowly as an institution.

And I am a nontraditionalist, so I work against a lot of the ideology of an institution, because of the lack of inclusivity of people of color or traditions around cultural context and cultural education.

And the way in which we talk about justice in an institution is really an injustice. Because [the institution] hasn’t quite figured out how to navigate broader spaces -- to not only have the student body be diverse but to be inclusive of decision makers who are sitting at the table, and to be willing to hear how those decision makers can create a more open space of an institution.

And that brings a level of discomfort for those who are donors and/or traditionalists or thought makers; they’ve always done it this way.

And so my work is to deconstruct that institutional ideology so that it is less colonial in its approach and more open. So that people feel like, “I can make space; my voice will be heard; my body will be respected; my dignity will be recognized. I will be seen in this institution, and I don’t have to apologize for being here.”

Q: How did you come to do this work?

I was born during the civil rights movement. I was aware of King’s presence as part of the leadership for the civil rights movement. I was raised in the black church during a time of civil unrest and oppression and marginalization and all of the “isms” that go along with being born with black skin.

I had this great awakening, if you want to call it that, when I joined Trinity United Church of Christ in the ’80s and my pastor was the Rev. Dr. Jeremiah A. Wright Jr.

And that was an African-centered spirituality, pedagogy, Bible understanding -- a theology that included women, womanist and black liberation theology -- which was for me very liberating.

Because I’m a person of African descent, and why should my education be limited to a white, Western, colonial understanding of history and church and methodology?

I came to it because it was important to make sure that liberation was always a part of, not only just the message that should be shared in the nation, but -- the church was holding that hostage. The Western sense of the white church dominates space.

And so I came to the work so that I could be part of the liberation. The African is the original human, in the creation, so how do we honor that as part of the world’s civilization? How do we honor those who were part of that Mediterranean, that African context, that Afro-Asiatic experience?

Jesus died for liberating people, not marginalizing, and so [my task is] making sure that people understand that there is no dominant culture, making sure that people understand that there is no dominant race of people.

And so I come to it out of this centeredness of being a descendent of those who were enslaved but were free, born free And so that’s how I came to it, and wanting to make sure that students and people I worked with in institutions that I was part of knew that that was my mission. That’s what God had called me to.

Q: You didn’t grow up in the UCC?

I was baptized Baptist, and I grew up in the UCC as a young adult; I was part of that church for about 20 years.

But you have to understand, Trinity United Church of Christ, even though it is a United Church of Christ church, was the largest black church in the denomination. And so I wasn’t as interested in the denomination as I was the church that I was attending.

Now I’m part of the denomination. Which is ironic, because I’m in a space now where the church is 5,000 churches, and 80, 85 percent of those churches are white. And, wow, that blew my mind, but here we are.

Q: How do you implement the ideas you’ve expressed? What does that mean day to day?

My day to day means that I’m paying attention to what the nation is doing to people of color. My day to day is reading, listening to what’s happening around xenophobia and racism around the globe.

My day to day really allows me to write and to think about how to create opportunities for churches to be engaged in the deep work of deconstructing whiteness. Because white skin, white privilege, whiteness is a construction.

And so my day to day is making sure that I am staying true to the anti-racism that the United Church of Christ is committed to as part of our bylaws and our resolutions. Making sure that the churches have resources that assist them in understanding who they are, not just as a denomination, but as a faith community.

Q: Do you ever find yourself in tension with your institution -- in a position of calling it to account?

No, because I’m really clear about what I’m there to do. I was hired to do this work. The search committee was looking for this new, innovative, creative bridging of both intellectual and heart with the church.

How does that happen if you don’t have someone in that space? How do you talk about indigenous peoples? And how do you talk about the immigrant, and how do you bring awareness and consciousness to the churches if you’re not fully present?

I have support from my colleagues, and I have a team leader and an executive minister who’s doing the work, and she models the work on the national stage while I do it within the space of creating those resources at the national level as well.

I approach it from a cultural-centered understanding or an African-centered understanding, but I’m also aware that that needs education, and it needs awareness and critical thinking.

And so I just released a curriculum, “Sacred Conversations to End Racism,” and we presented it to the national staff last week.

Another colleague and I, the Rev. Tracy Wispelwey, developed a podcast during the Lenten season, “Podcast for a Just World: Sacred Conversations to End Racism.” We were intentional about doing anti-racism work, and it was received well.

People want to be engaged in the conversation. They want to be part of activism. They just sometimes don’t know where and when to start, or how to, and so our job is to assist them with their journey.

Q: If congregations or individuals within your denomination come to you with those questions -- “How do we get started? What do we do?” -- what other resources do you give them?

I believe in doing this work because “race is not real, but racism is.” That comes from the Rev. Traci Blackmon.

It is to point them in the direction of being immersed in someone else’s culture. It is having them read text, Scripture, the Bible, out of the cultural context. It is them doing the work of understanding what it means to be white.

It is them doing the hard work of sitting, struggling, wrestling with not only what that means but what it means to give up that whiteness. Because God did not create race or racism. And so what does that really mean? I have to sit with that.

And if it’s a painful place, then the work that we do is to say, “Yes, feel that. Because you’re living in 600 years, 400 to 600 years of people living in pain, living on the margins, living and feeling the brunt of not being seen as human, and being invisible, being incarcerated, being murdered for being black or being indigenous or being an immigrant.

“And so read, listen, learn from and then do the work of educating people within your congregation, your conference, so that you can be part of this work of dismantling racism and not a colonizer.”

I think it’s easier to stay in a colonial mindset than it is to be part of disrupting and dismantling.

But there are also some great colleagues who are part of the sanctuary movement, who are providing shelter for those who are being deported.

There’s a great understanding of what it means to be on the front lines and to be marching in D.C. or to be part of the Poor People’s Campaign or to be connecting with organizations and faith-rooted organizations that are doing civil disobedience work.

So we’ve got all of that within our denomination, and we’ve got people committed to it.

But perhaps [for] those who are not there yet, that’s why I’m there -- to help them get started and to help them stay on the journey. It’s not just, “I’ve done a march; I’ve read a book; I’ve talked to my neighbor who’s different.”

But that difference means that that’s another beautiful human creation of God, and [that means] not othering them or exoticizing them or treating them as if they are deficient because they’re different -- because they are equally human.

And so that journey is lifelong, and I want to be able to create those kinds of resources where people are constantly watching movies and documentaries and reading and learning another language.

Q: Can you explain what you mean by a colonizer?

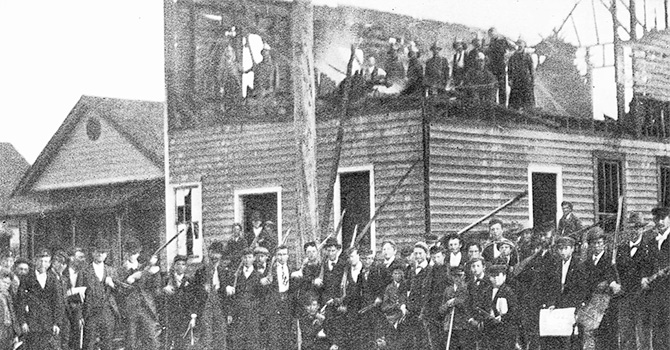

A colonizer is someone who thinks that people need to fit into their culture and their systems and their structures to belong. The nation was colonized by Europeans. And so when you conquer the land, you create and control the narrative. You create and control the laws. You write into policy how people live and earn their economic status.

When you colonize, you create education that teaches a perspective about a people group and you leave out others, or you mythologize your own history in order to create this superiority.

A colonizer takes land, gentrifies, names people, decides to build walls, keeps people out of the church because they’re uncomfortable. That’s a colonizer.

Q: Thank you. Where do you see the most important direction of your work? The last few years have brought these issues to the fore.

The issues aren’t new, but it’s the approach that I am trying to create -- I’m building on other people’s approaches, this liberation that we call theology and ideology and so forth.

And so I see it being a space and a place that grows into changing the narrative of our history, changing the way that we educate our children, so that people are getting cultural education, as opposed to a colonized or Western education.

I see my work being part of changing this narrative, this landscape, this idea that there is not a dominant [culture], so that people can then speak into it, live their lives freely.

How do we change our economic system?

I see this being an opportunity for people to understand where money came from and who controls it so we can talk about equity. Our prison industrial system is being propped up by those who own stock in making sure that those buildings go up and that prisoners stay prisoners. It’s another form of enslavement. And so I want people to be aware of that and hold people responsible.

I see this being a national effort to change how we educate, how we preach, how we teach, maybe developing an institution where thought leaders come together and they do what Starbucks did -- they close down. Not just for a day, but close down for maybe a day a month. Or every week there’s a day where they commit to this process of looking at what it means to have an equitable society.

Q: Is there anything that you would add that I did not ask you about?

I don’t do this because it’s just work, because I’ve been hired by the United Church of Christ. I do this because I am passionately in love with serving God.

I’m deeply committed to doing this work because I know that people are being hurt by the way that this country demonizes and ostracizes and murders. And how do you separate a child from its mother just because they cross the border? Whose border?

I do this work because people need to feel as if they can live and breathe and move without being threatened and detained.

I am passionate about this work, and I love that people want to be engaged in this and ask the questions and commit to saying, “I’m willing to give this up to do this.”