Preachers do not step into the pulpit just because another Sunday morning has rolled around. We don’t preach just for the sake of preaching. For some of us, especially black pastors in the United States, preaching is an opportunity every week to invite human beings to participate in the in-breaking reign of God.

The idea that such in-breaking is even possible is not a feel-good, idealistic notion. It is the ground upon which black preachers have built and sustained their abiding belief that God’s justice, freedom and peace can exist on earth. As a result of this commitment -- idealism, some might call it -- black preachers have long worked to repair the dilapidated structures at the intersection of American theology and politics.

In the wake of the recent presidential election, the deterioration and decay at that intersection is more visible than ever before. What now is the role of black preaching in this new age, in this new America of soon-to-be President Donald Trump?

Certainly, black pastors from the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to the Rev. Dr. Jeremiah Wright have warned for generations that America’s house is on fire with injustice and oppression. Do we follow King’s call and be America’s firefighters, helping to extinguish the fire and save the house? Or, given the election results, is it time to abandon the house -- both America and its Christianity -- and condemn it as unsalvageable?

Most black pastors and their congregations live with these tensions in one way or another. They know that Christianity -- even American Christianity -- is neither inherently white nor incompatible with black life in America. But as they work to see and to bring about the in-breaking reign of God, many -- if not most -- fall somewhere in the middle. They are not willing to live in a house aflame with oppression and injustice, but neither are they willing to abandon the American project and the Christianity that underwrites it.

But how fertile is that middle ground? Is it even safe? In the current context of Christianity in America, how can one possibly preach in such a way that a congregation can not only envision the reign of God but also find it irresistible? Can the preached word really help dismantle and ultimately defeat the powers arrayed against that reign? How can pastors even talk of political and theological freedom in a time of such racial strife and tension?

For some insight, we would do well to consider the theology of Richard Allen, the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. For Allen, who lived for years in slavery before buying his own freedom, Christian conversion was not an end in itself. After becoming a Christian, he studied theology and began thinking and reflecting theologically, eventually asking himself the following question:

What does being Christian and my understanding of that theology mean for the condition of my body and the bodies of my fellows?

As he pondered that question, Allen, I believe, worked in the best tradition of Trinitarian theology. God, he realized, is radically free and sovereign within God’s Triune life. The Father does not control or subvert the Son. The Son does not control or subvert the Spirit. The Triune God exists in self-disclosing, other-affirming love. And if all that is so, then human communities are to model the life of God. They are not to be controlled or subverted by other human communities. People must be free to live in community with one another even as God lives in community with Godself -- absent coercion, control and subversion.

Allen’s theological reflection led him to preach and to act squarely within the American narrative, while at the same time pushing that racialized narrative to something new, something that could not be called “American” at all. In his preaching and advocacy, he promoted something both unlawful and unimaginable to the powers that ruled America: that Africans in America, both enslaved and free, were not mere observers or bystanders but “citizens” with the power to make things happen in the land where they found themselves.

Allen clearly used American language and symbolism in his preaching and public rhetoric. But he also used African-American language and symbolism to demand liberation for his fellows and to insist on the reign of God in this life, not another. Working with God as co-creator, he moved beyond speech to acts, beyond rhetoric to building.

With God and his peers, both female and male, Bishop Allen founded the Free African Society in 1787, the forerunner of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Later, in September 1830, Allen’s theological reflection again gave way to liberative action when he brought together black leaders from seven states for the first National Negro Convention, a gathering to address various issues weighing upon the black masses.

But what does this have to do with America and black preaching in this time of Advent 2016?

What Allen teaches us is the power of holy speech born of theological reflection made flesh by and within a community committed to a new world -- a world endowed with freedom. Allen helps us understand the ways theological reflection brings about visioning; the ways the preaching moment, as speech act informed by theological reflection, can challenge current discourse and imagine a new world; and the ways co-creation can be institutionalized to sustain the vision and speech acts.

Yes, preaching is a textual enterprise. The words of preachers are shaped by texts that particular communities of faith have chosen to elevate theologically. But that does not mean we are to accept texts uncritically or with narrow interpretations. We cannot be in love with texts for the sake of the texts; rather, we must be in love with freedom and the liberative possibilities that lie dormant in texts until speaking -- preaching -- rightly animates them.

This is nothing new for African-Americans. Black writers and their readers have long woven the biblical text into their ancestral theological and philosophical understandings. The Bible has never been uncritically holy; it is holy only where and when it affirms the liberating character of God and the freedom of human existence.

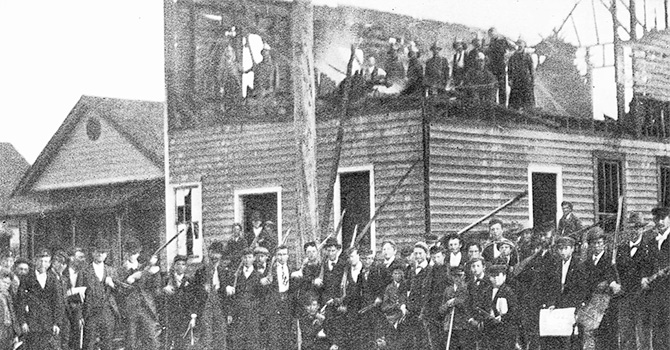

So yes, just like Allen, black preachers today must continue to mount pulpits in the face of black struggle and discrimination. Remembering him and his times helps us understand that racism and the disdain for black life by many in America today is not an anomaly. Neither is the result of our most recent presidential election. They are both American.

We cannot hide from historical truth in America -- not if we are serious about finding a new way forward. That history is painful, but for whom? As James Baldwin has told us, “The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.”

History lays bare our complicity in making a nation and a world that unfairly advantages some and disenfranchises others. We can no longer afford to indulge in the national rhetoric of freedom, justice and equality. Neither can we simply hope for it. Hope rests in the fighting. So we must fight for the real thing.

Not long ago, most of our leaders and scholars -- whether Democrat or Republican, liberal or conservative, of African or European descent, Christian or Muslim -- could easily assent to the orthodoxy that America is a good and moral nation, one ordained by God for a special purpose. Any violence in America’s history -- at least, where we were not the perpetrators -- was the work of isolated individuals not to be woven into the tapestry of national memory. But that is no longer the case. A new understanding, a new orthodoxy, is possible, but not until our theology and our politics deal with the complexities of American history.

Can there be a new day in the American body politic and in the American church? If preaching, especially black preaching, retains its memory, theological visioning, speech acts and co-creative possibilities, we have hope.

This Advent, as we await the coming of God, God is waiting for us to envision and create something new for this moment. Will we do God’s will and usher in God’s reign here on earth? Or will we posture in adoration bereft of hope as we watch a national and global house aflame?