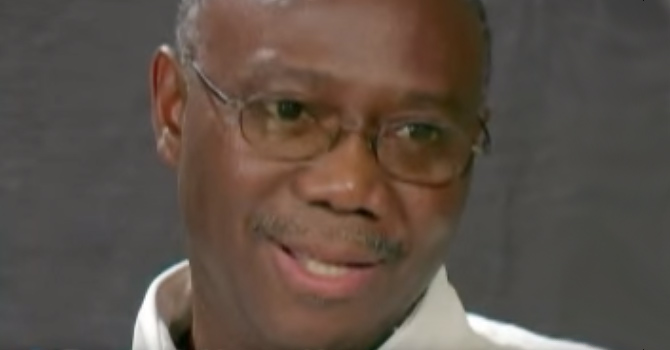

The Rev. David Kasali educates Christian leaders in war-devastated Congo to help people living in suffering and lament discover the good news. In Congo, he said, it is as if you’ve been having 9/11 every day for more than five years. “Over there, it’s not classroom theology. It’s the theology of the street, it’s the theology of the village,” he said.

Kasali is rector of the Bilingual Christian University of the Congo. He founded the non-denominational university in 2007 after serving for nearly a decade as president of Nairobi Evangelical Graduate School of Theology (NEGST). Kasali earned a master’s degree at NEGST and a doctorate at Trinity International University in Chicago. He is ordained in the Africa Inland Church, and serves as president of the Congo Initiative, which he co-founded with his wife, Kaswera Kasali.

While at Duke Divinity School’s Summer Institute, Kasali spoke with Faith & Leadership about the role of his university in helping Congo recover from years of war. The video clip is an excerpt of the following edited transcript.

Q: How did you decide to build a university in North Kivu Province of the DRC?

That is where my people are. For many years that area suffered with war as its eight neighboring countries invaded Congo. And during that time my big brother died, my younger sister died.

During the war I felt, “Why am I outside of the country? I need to go and be with my people.”

My wife said, “But there’s war there!” I said, “Of course there’s war, but our people are there, too.” She said, “But people are dying there!” I said, “Of course they are dying. So why should they do the dying for us? We need to be there and be with our people.”

I remembered at that time the Bible verse that I memorized as a child with missionaries who taught me: By faith, Moses, when he was growing up in the house of Pharaoh, he refused to enjoy the pleasures of that house. He decided to go, and lament with his people, and give them hope.

So, for me, it was not a matter of choice. It was a matter of necessity. It’s my people. What do I gain staying away from my people while my people are suffering? Better to be with them.

Who knows whether it is for a time like this that God prepared me to be who I am, to study, to be able to be a voice of my people, but also train them to confront what is happening to them.

Q: What’s difficult about starting a university from scratch in North Kivu?

Oh, my goodness! Starting a university in the DRC, it’s a challenge, it’s a matter of faith because almost all the infrastructure, the services, and civil services in Congo are completely destroyed. So the challenge is enormous. You don’t have books. You don’t have libraries. You don’t have teachers. The teachers there have that traditional, educational model where professors are almost like priests who lord it over the students and make students memorize their courses.

But, at the same time, that’s where it is good to start because that is where it is most needed, because that is where the impact of anything small that is good is felt so quickly.

So, building the university from ground up was tough. We had to buy a piece of land big enough so that we can also do agriculture on the land. We had to have the first building that was not even complete but we are using the classrooms there.

And we take the younger Congolese who finish their master’s [degrees], and then we retrain them to be teachers and teach in an interactive way, and not the way they used to teach. And then we take some teachers from outside the country, especially from America, to go and mentor the teachers there, and co-teach with these teachers, and also develop our programs.

And the good side about it is that you don’t have a history behind you to tie you down. You’re free to start new things. And actually it has helped us to have favor before the government because the government in Congo is starting a new system of education and the universities are reluctant. All the universities are reluctant to move toward that because it is shaking the status quo and so they are asking us to be the first to start this new educational system in the fall which is closer to the system of education in America.

So it’s opening the country wide open to us to influence the nation with a new type of education that is solid as an education but also based and grounded on the ethics of Jesus Christ.

Q: What do you say to claims that in a devastated country like the DRC there are greater needs than a university?

That’s true. Maybe two things I would say about that. Relief work is needed and it is often preferred, because you can count and you can see an immediate impact: “We fed 2,000 families, we relocated them, and it is good.” But it will not work in the long run.

Certain problems will repeat themselves. You have to go to the roots. The root for me is leadership. Our suffering in Congo is dependent on the type of leaders that we have. If we can prepare a new generation of leaders who are critical in their thinking, who are grounded in ethics of love your enemies and love your neighbors, and who say, “Enough is enough,” then in the long run we will change to a sustained development that will do away with the relief work.

It is very important to do it at a university, because it will give us leadership who will be able to analyze what the questions are. Often we go there and we want to help people, and we help them; and sometimes at the end of our help the people say, “Well, thank you for giving us the answers -- but what was the question?”

We need local people to know local questions, analyze local questions and be in dialogue with people who are coming to help. It’s very important to develop the new generation of leaders who are not only able to analyze the issues but to sit around the table of conversation with people from around the world and bring, not only their ideas, but the voices of Africa.

Q: What is it about the church in Africa that makes it possible to found institutions like the Bilingual Christian University of Congo?

Africans don’t dichotomize between secular and religious. It is all part of us. If it’s not Christianity, it’s another thing. That gives us a platform, a connecting place to say, “Well, wait a minute. Let’s try Jesus.” Our faith is very much integrated to our daily life. That makes it easier for us to integrate faith in learning.

Q: How would you answer someone who said, “Why would you start a university in a place where war could break out at any minute?”

Well, we cannot be controlled by fear. Of course we have to be wise, but often the people of God are not bold enough. Congo is full of natural resources, and there are many people inside and outside the country who are working at stabilizing the country so that they can exploit the country.

Why should Christians run away where they are most needed? The church of Jesus Christ can’t run away from lament. That is where we have to be, and so we have started a Christian university there.

Q: What’s particularly important to teach in a Congolese context?

The country is really destroyed. First it has to be on a biblical, theological foundation of the dignity of human beings. Then we have to develop all the other spectrum of learning.

We need documentaries teaching people to deal with issues of HIV/AIDS, rape, tribal conflict and economics. How can we do business in a Christian way so that we’re investing in the country? We are paying people well.

Why should we let politics be in the hands of people who don’t know God, who do not have love for their country? We need to teach people how to do politics so that policies are in favor of people.

For many years the country has been outside of globalization, but now technology just came in, and we don’t have people who can handle this technology. We have to provide them. It’s not about “me.” It’s about a new “us” that you want to build between tribes, and races, and people who are educated [and those] who are not educated, and this new generation who are saying, “We need to create a new place where we share our way together.”

Q: Your vision goes on and on.

It goes on and on because the need is so vast. We try to start small, we try to do well in what we are doing and we try to do it soon. Then we don’t do anything unless we find champions: people who love it, people who have the skill to do it and people who can sustain it in the long run. In everything we do, we want to make sure that local people are saying, “Yes, this is ours. We like it and identify with it, and we see that it will really have an impact in the community.”

Q: You trained as a New Testament scholar in the United States. How is it different to teach New Testament in the context of the DRC?

I did my Ph.D. in New Testament in America, and I was not in Congo when war was going on, and I had all these beautiful textbooks with biblical theology and New Testament theology.

Over here, you have 9/11. In Congo, it is as if you’ve been having 9/11 every day for over five years. Over there, it’s not classroom theology. It’s the theology of the street, it’s the theology of the village: “God, where are you when we are suffering?”

The many women who have been raped, gun raped … There is a hospital there in Goma; I am a board member. There are women who have been operated on, but some of them cannot be helped and they have been rejected by their families; they have a camp where they live on their own. We see all of that.

I ask myself, “What is good news? What is the gospel?” If you come to such a woman in Congo, [or] a man who lost his children, [and] you say, “God loves you. Jesus died for you. You’ll go to heaven” -- what is good news for my people? It must be more than a definition in a classroom. If it stops there, my people will say, “Well, I’ll think about that tomorrow.”

We had a consultation with women who had been raped and with prostitutes; they said we don’t want to be in this situation. We couldn’t say, “Go and warm up and eat well.” We started a center for women where we give them skill training, skills that they can use for livelihood.

We are teaching them on sewing machines. We have only three sewing machines, but we’re teaching them. We teach them soap making. We teach them how to make beads. We have 20 of them. That’s the gospel. The gospel is more than sending us to heaven. The gospel is teaching us how to live on earth the way Jesus wants us to do that. And you cannot get that from the classroom.

The classroom cannot teach you to weep. Jesus wept. And being in Congo brings tears to your eyes, and you identify with the oppressed. Theoretical learning gives me the critical tool to go beyond what I learned to find how the gospel of Jesus Christ is relevant to my suffering people.

Q: Are you saying universities aren’t enough by themselves?

Universities should give us tools on how to do, and then our lives should be lifelong universities on using these tools to bring answers to the questions that people are asking. In our university we say that we are being transformed to transform. We cannot finish university studies without being transformed.

Q: There has been a surge of interest in Africa among Western Christians. Why do you think that is?

I like that interest of America to Africa, but I hope it will not be an interest of tourists. I hope it will not be a helicopter visit -- jump in and out. I hope it will be catching the fire, catching the passion. I hope it will be identification and incarnation. I hope it will be walking our walk, walking the long run.

It is not easy. This is taking on pain. But if we are the church, we have to do what Jesus did. This past year we had 10 young Americans in Congo at the university with us. We were together. We have to come together to form a community, and this is what we are doing now, forming the community.

When you come, I want you to live with me, eat with me, play with me, suffer with me and cry with me. That’s what we want. I think in the years to come we will not need missionaries. We’ll need brothers. We’ll need sisters. We need to have an identification with the people.

Q: What is it like as founding president of a university as opposed to leading a larger, established institution?

I’m happy, because something small can go a long way, but equally, something small can be a big challenge, so it keeps me under the cross of Jesus Christ, and keeps my faith going, and keeps John Chapter 15 very real: “Remain in me and me in you; without me, you cannot do it.”

Being there, I have to depend completely on God, and that without him we can do nothing.