The church in the United States has had a long and troubled history with race and racism. And though most people today agree that racism is bad, many Christians still operate out of deeply held social intuitions -- basically, gut feelings -- about race, shaped by the broader culture and even Christian culture, says Drew G.I. Hart.

“We all have to take responsibility as a society,” Hart said. “Maybe we’re not overt about it, but we’re all participating in a racialized society in which none of us have our hands clean.”

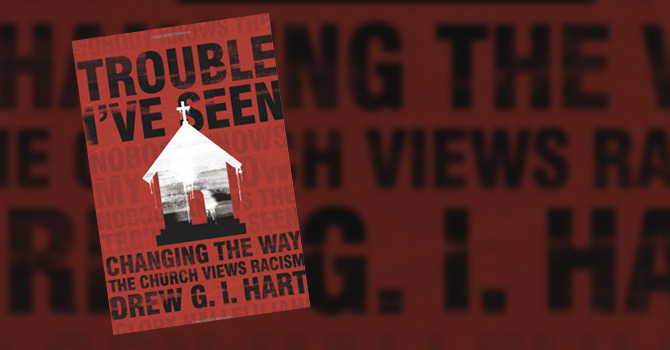

An assistant professor of theology at Messiah College, Hart is the author of “Trouble I’ve Seen: Changing the Way the Church Views Racism,” published in January by Herald Press. In the book, Hart urges the church to move from a “thin” account of race and racism to a “thicker,” more complex understanding that acknowledges how race shapes our lives and communities.

“We’re all navigating race and racism every day,” he said. “The question is, are we doing it faithfully? Are we aware of this long narrative of history that shapes our lives, and are we resisting it in a way that honors Jesus Christ?”

Though it may sound simple and pious, one of the most important ways Christians can resist racism is to “recover” Jesus, taking Jesus and Scripture seriously, he said.

“If we begin to take seriously this story of Israel, fulfilled in the story of Jesus, it really disrupts the white supremacist narrative,” Hart said. “You can’t live into that and follow Jesus faithfully.”

Hart has a B.A. in biblical studies from Messiah College, an M.Div. from Biblical Seminary, and a Ph.D. in theology and ethics from Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia. This fall, he will begin teaching full time as an assistant professor of theology at Messiah College.

Hart was at Duke Divinity School recently to teach a seminar at the Summer Institute for Reconciliation and spoke with Faith & Leadership. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: To start, tell us about your book, “Trouble I’ve Seen: Changing the Way the Church Views Racism.”

I wrote it after I finished my Ph.D. comprehensive exams. Instead of starting my dissertation, I wrote that book.

It was after Michael Brown’s killing in Ferguson, Missouri, and the protests that arose. I wanted to speak to the church about what was going on and to give both a social and a theological framework for entering into these conversations.

The book tries to move the church from having a thin definition of racism to a thicker definition that understands racial hierarchy and what that actually means every day -- how our society is racialized, and how that shapes our lives and our communities.

I wanted to give the church a theological way of thinking about this. How do we reflect on the story of Jesus and maybe respond a little bit more faithfully as a church than we have in the past?

Q: How has the church viewed racism historically?

It’s complicated. Today, everyone agrees that racism is bad, but how we even define racism is often so slim. We’re usually talking about the “bad” people, people “out there” -- the KKK and people who are engaging in overt racism.

What I’m trying to do is not to see racism as a problem that’s “out there.” We all live in a society that has shaped us unconsciously in ways that we can’t even begin to imagine until we take the time to do some deep self-examination and serious reflection on America’s past and present.

A few years ago, for example, Paula Deen said some really ugly stuff. Well, it was interesting watching how people responded. Almost everybody wagged their finger -- “Bad Paula Deen!” But they did it in such a way that she’s this isolated problem, rather than realizing that Paula Deen was socialized by communities.

She didn’t create this stuff; she didn’t invent this. She was shaped by communities that socialized her way of thinking and acting and speaking.

We all have to take responsibility as a society. Maybe we’re not overt about it, but we’re all participating in a racialized society in which none of us have our hands clean.

We’re all navigating race and racism every day. The question is, are we doing it faithfully? Are we aware of this long narrative of history that shapes our lives, and are we resisting it in a way that honors Jesus Christ?

Q: So what’s been the relationship between church and race in the United States?

On one hand, very early, some deep theological work was done to help foster and justify race and racism and the system of slavery.

At the same time, African Christians were reinterpreting the life of Jesus and the significance of Jesus in a very different way. They knew that Jesus was not endorsing slavery but was a liberator and a friend of those who suffer, someone who came alongside them in the midst of hard times.

So there have always been these differences. There are these ebbs and flows and challenges and contradictions deeply embedded in American Christian faith as it relates to race and racism.

But overall, the dominant narrative of race and racism and the church is a very ugly one. Very few traditions have been able to sustain an ongoing community generation after generation that doesn’t just go with their gut about race. And by that I mean the socialized intuitions around race and racism.

Most people can agree that from 1619, when the first Africans were brought over, up until the mid-20th century, most white Americans had been socialized in such a way that they did not recognize racial injustice and oppression. But today we look back and we’re like, “Oh yeah, they were missing it, right?”

That’s not really controversial.

But today we are still in the same situation. Many Christians still operate out of their social intuitions around race and racism, shaped by the broader culture, or sometimes by Christian cultures. They still just go with their gut.

That is an opportunity for us to think about the life of Jesus. It’s a different way of engaging the world and seeing the issues when we explore the world from the vantage point of the crucified Christ. And it’s a very different posture entering into these conversations as the church.

Too often in America, the church is caught in these patterns rather than being the one breaking out of the patterns and bearing witness to the kingdom of God on earth.

Q: You said you want the church to move from a thin to a thicker account of race. What’s the thin account and what’s the thick?

The thin account is the very individualistic framework of race and racism. It’s, I don’t like somebody because they’re black, or whatever their skin color is.

We have in our minds, again, the KKK and cross burnings and stuff. We think that’s what racism is, this very static understanding of racism. It’s very individualistic; it’s about personal prejudice or hatred from one person to another.

A thicker definition, for me, would be to take seriously the development of race over time in history.

Why was it constructed? What was it doing? What were the sociopolitical ramifications, the economic ramifications? How did it classify people into hierarchies? How is it a widespread phenomenon?

That’s a much thicker definition that engages and is in conversation with the sociology department -- not just thinking individualistically, but trying to stretch our minds to think about the social ramifications of race and racism.

It’s also, really, at the end of the day, taking seriously people’s experiences and listening to those stories and stepping back and making sense of the realities that people confront every day as it relates to even simple things like housing, education, jobs and opportunities.

It’s broadening our understanding that racism isn’t always mean people doing things; it’s not always overt racial prejudice. There are all these other forces at work in our society and in our lives that we’re sometimes unconscious of.

Q: Is it possible to talk about racism in the United States and the church without talking about white supremacy? Aren’t racism and white supremacy two sides of the same coin?

Once we get that thicker understanding of race and racism, it forces us to talk about racial hierarchy -- which is to say that race was never a neutral term.

Race was something that was constructed, a humanly constructed idea. It’s not the same thing as talking about ethnicity; it’s not a natural, biological category.

In Europe, especially during modernity, people tried to classify humanity as they observed it from their vantage point. They thought they were being objective, and they tried to classify it just like they classified everything else. It was a pseudoscientific imagination being played out as they encountered for the first time what they thought were new worlds.

But this racial hierarchy is not neutral; it was always about white supremacy.

It’s imagining white as everything good and right and beautiful in the world; the most central component of the racial hierarchy has often been anti-blackness.

And the hierarchy is not static but dynamic. It plays out in different ways in different regions.

So yes, we have to be able to talk about white supremacy. The goal of race was always either to give white people social dominance or, at the very least, to give a psychological edge to poor white people who are being crushed by some of these same systems.

Not everyone is really participating in the dominance. But certainly, everybody’s being shaped by how it’s informing their identity in the world and how they see other human beings -- the kind of belonging that they’re able to have with other people, and who they can’t imagine belonging with.

Q: And as you said, the hierarchy, with its categories, is dynamic and changing. Different ethnic groups come to America, and the definition of “white” changes.

Yes. At the center, in its origins in America, are Anglo-Saxon Protestants. So if you were Italian or Irish, you were not white. Read Thomas Jefferson and Ben Franklin; they’re making fun of even Germans.

We don’t realize how arbitrary and malleable and dynamic these categories are. They’re changing over time and according to the whims of the majority.

Race actually changes and expands and thins out. Who’s in and who’s out changes. These are not as fixed as we imagine them to be as categories.

On one hand, they’re socially constructed; on the other hand, they’re lived realities that we have to embody.

So sometimes we can’t make sense of the two at the same time. Either we only think about it as our lived reality or we only think of it as a social construct. But they’re actually both simultaneously.

Race is very real, like this table is real. But race is also constructed; it’s a lie, in terms of the biological claims and differences in humanity. It’s a lie, but it does shape our lives.

So we have to account for those realities and figure out, where do we go as Christians moving forward?

Q: So what’s the role of the church in this? How do you change the way the church views racism?

One is creating communities where we have space to have open, honest, truthful dialogue. Often, churches are very monological. There’s no space for that kind of engagement -- to be truthful and work through stuff in community.

Absent that, it’s very hard to change, unless the person who’s controlling the monologue is open to engaging in these conversations.

Having a dialogical community is important. But more important is to recover Jesus.

That sounds kind of simple and kind of pious. But I really believe we’ve so domesticated and distorted Jesus to the point that this man that was a Jew living in first-century Palestine eventually becomes the possession of the West.

He becomes a figure that is possessed and controlled by the West itself, and loses his relationship both to what it meant to be a part of the covenants of Israel and to what Willie James Jennings talks about in “The Christian Imagination” as [our forgotten] Gentile identity and how we enter in the story.

It is very important for us to recover our own sense of Gentile-ness, so to speak, as we approach Jesus and Scripture and Israel’s story. Communities that have seen themselves as the new Israel and the saviors to the world -- all of a sudden, we’re displaced and instead are Gentiles being engrafted into somebody else’s story.

And that requires us to take somebody else’s story seriously and see that in entering somebody else’s story, there’s grace, rather than feeling like everyone’s got to come through us and become like us to meet Jesus.

So that’s one aspect.

Another is to read our Scriptures a little more seriously and maybe a little bit more subversively. There’s something subversive about what happens when you read the narrative as a whole, particularly when you read it through the lens of Jesus Christ.

It’s interesting. How is Jesus reading Scripture as he sees the prophets playing a particular role in interpreting the meaning of Israel’s story and what God intended? You have a very radical understanding of this God who has always sided with the poor and the oppressed, the widow and the orphan, the marginalized, and who calls even Israel to remember when they were once enslaved.

And this prophetic tradition is fulfilled in the story of Jesus as he comes alongside the poor masses, vulnerable women, the Samaritans. Those are the folks he clings to, those who are sick and have no access to the rest of society. He says the least, the last and the lost are the folks who are going to have a privileged space around God’s kingdom.

So if we begin to take seriously this story of Israel, fulfilled in the story of Jesus, it really disrupts the white supremacist narrative. You can’t live into that and follow Jesus faithfully.

It disrupts even our sense of American exceptionalism and how we engage around the world. All these things, these narratives that we live by, get disrupted by the story of Jesus when that becomes our own story.

Certainly, we like to call ourselves a Christian nation, and people are quick to name Jesus -- “Yeah, I love Jesus.”

That’s great, but we don’t necessarily want to follow Jesus and take Jesus seriously. We’ll skirt Jesus at every opportunity when it disrupts our own narratives.

Q: Where do you see that most vividly in Scripture in Jesus -- the subversiveness that you’re talking about?

I love the four Gospels. I feel like they get so neglected.

Each of them presents this Messiah that really flips the world upside down. All four together give us a vivid portrait of who Jesus is that really brings him to life in a way that the domesticated version of him can no longer remain.

It’s really about embodying and making the story of Jesus visible, both in our individual lives and then fleshing that out in community.