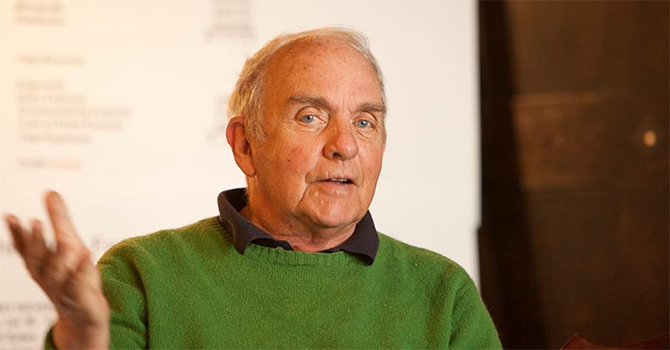

Frederick Buechner is a theologian, ordained Presbyterian minister and writer. He’s also an unlikely social media sensation, with more than 1.5 million followers.

On July 11, 2016, he turned 90, an occasion marked by the publication of “Buechner 101: Essays and Sermons by Frederick Buechner.”

Edited by writer Anne Lamott, the volume features a selection of Buechner’s essays and sermons, as well as excerpts from his memoirs and novels. It also offers tributes by others, including Barbara Brown Taylor and Brian McLaren.

In the introduction, Lamott says that Buechner “writes of the truth, both of the Gospel, and of his own damaged family, and of our truth, sight unseen, … in a way that is so precise, revelatory and profound, that it makes me experience an awakening to spiritual reality all over again, each time.”

The following excerpt is Buechner’s commencement address at the Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, Virginia, originally published in “A Room Called Remember.”

JOHN 14:6

Jesus said to him, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life.”

Here I am, and there you are. That is the crux of it. Here I am, the stranger in your midst. There you are, who are the midst, who are the graduating class, who are friends and classmates and sweethearts of each other, who have brought your friends and families with you and yet who are -- all of you, even those of you who have known each other for years and whose hearts are sweetest -- as much strangers to each other in many ways as I am a stranger to you all. Because how can we be other than strangers when at those rare moments of our lives when we stop hiding from each other and try instead passionately and profoundly to make ourselves known to each other, we find this is precisely what we cannot do?

As ministers, preachers, prophets, pastors, teachers, administrators and who knows what-all else of churches, you will be leaving this lovely place for places as lovely or lovelier yet or not lovely at all where you will take your turn at doing essentially what I am here to do now, which is one way or another to be, however inadequately, a servant of Christ.

And yet in another sense we are none of us strangers. Not even I. Not even you. Because how can we be strangers when, for all these years, we have ridden on the back of this same rogue planet, when we have awakened to the same sun and dreamed the same dreams under the same moon? How can we be strangers when we are all of us in the same interior war and do battle with the same interior enemy, which is most of the time ourselves? How can we be strangers when we laugh and cry at the same things and have the same bad habits and occasionally astonish ourselves and everybody else by performing the same uncharacteristic deeds of disinterested kindness and love?

We are strangers and we are not strangers. The question is: Can anything that really matters humanly pass between us? The question is: Can God in his grace and power speak anything that matters ultimately through the likes of me to the likes of you? And I am saying all these things not just to point up the difficulties of delivering a commencement address like this. Who cares about that? I am saying them because in the place where I am standing now, or places just as improbable, you will be standing soon enough as your turn comes. And much of what this day means is that your turn has come at last.

As ministers, preachers, prophets, pastors, teachers, administrators and who knows what-all else of churches, you will be leaving this lovely place for places as lovely or lovelier yet or not lovely at all where you will take your turn at doing essentially what I am here to do now, which is one way or another to be, however inadequately, a servant of Christ. I wouldn’t have dreamed of packing my bag and driving a thousand miles except for Christ. I wouldn’t have the brass to stand here before you now if the only words I had to speak were the ones I had cooked up for the occasion. I am here, Heaven help me, because I believe that from time to time we are given something of Christ’s word to speak if we can only get it out through the clutter and cleverness of our own speaking. And I believe that in the last analysis, whatever other reasons you have for being here yourselves, Christ is at the bottom of why you are here too. We are all here because of him. This is his day as much as, if not more than, it is ours. If it weren’t for him, we would be somewhere else.

Our business is to be the hands and feet and mouths of one who has no other hands or feet or mouth except our own. It gives you pause. Our business is to work for Christ as surely as men and women in other trades work for presidents of banks or managers of stores or principals of high schools. Whatever salaries you draw, whatever fringe benefits you receive, your recompense will be ultimately from Christ, and a strange and unforeseeable and wondrous recompense I suspect it will be, and with many a string attached to it too. Whatever real success you have will be measured finally in terms of how well you please not anyone else in all this world -- including your presbyteries, your bishops, your congregations -- but only Christ, and I suspect that the successes that please him best are very often the ones that we don’t even notice. Christ is the one who will be hurt, finally, by your failures. If you are to be healed, comforted, sustained during the dark times that will come to you as surely as they have come to everyone else who has ever gone into this strange trade, Christ will be the one to sustain you because there is no one else in all this world with love enough and power enough to do so. It is worth thinking about.

Christ is our employer as surely as the general contractor is the carpenter’s employer, only the chances are that this side of Paradise we will never see his face except mirrored darkly in dreams and shadows, if we’re lucky, and in each other’s faces. He is our general, but the chances are that this side of Paradise we will never hear his voice except in the depth of our own inner silence and in each other’s voices. He is our shepherd, but the chances are we will never feel his touch except as we are touched by the joy and pain and holiness of our own life and each other’s lives. He is our pilot, our guide, our true, fast, final friend and judge, but often when we need him most, he seems farthest away because he will always have gone on ahead, leaving only the faint print of his feet on the path to follow. And the world blows leaves across the path. And branches fall. And darkness falls. We are, all of us, Mary Magdalene, who reached out to him at the end only to embrace the empty air. We are the ones who stopped for a bite to eat that evening at Emmaus and, as soon as they saw who it was that was sitting there at the table with them, found him vanished from their sight. Abraham, Moses, Gideon, Rahab, Sarah are our brothers and sisters because, like them, we all must live in faith, as the great chapter puts it with a staggering honesty that should be a lesson to us all, “not having received what was promised, but having seen it and greeted it from afar,” and only from afar. And yet the country we seek and do not truly find, at least not here, not now, the heavenly country and homeland, is there somewhere as surely as our yearning for it is there; and I think that our yearning for it is itself as much a part of the truth of it as our yearning for love or beauty or peace is a part of those truths. And Christ is there with us on our way as surely as the way itself is there that has brought us to this place. It has brought us. We are here. He is with us -- that is our faith -- but only in unseen ways, as subtle and pervasive as air. As for what it remains for you and me to do, maybe T. S. Eliot says it as poignantly as anybody.

... wait without hope

For hope would be hope of the wrong thing; wait without love

For love would be love of the wrong thing; there is yet faith

But the faith and the love and the hope are all in the waiting.

Wait without thought, for you are not ready for thought:

So the darkness shall be light, and the stillness the dancing.

It’s a queer business that you have chosen or that has chosen you. It’s a business that breaks the heart for the sake of the heart. It’s a hard and chancy business whose risks are as great even as its rewards. Above all else, perhaps, it is a crazy business. It is a foolish business. It is a crazy and foolish business to work for Christ in a world where most people most of the time don’t give a hoot in hell whether you work for him or not. It is crazy and foolish to offer a service that most people most of the time think they need like a hole in the head. As long as there are bones to set and drains to unclog and children to tame and boredom to survive, we need doctors and plumbers and teachers and people who play the musical saw; but when it comes to the business of Christ and his church, how unreal and irrelevant a service that seems even, and at times especially, to the ones who are called to work at it.

“We are fools for Christ’s sake,” Paul says. You can’t put it much more plainly than that. God is foolish too, he says -- “the foolishness of God” -- just as plainly. God is foolish to choose for his holy work in the world the kind of lamebrains and misfits and nitpickers and holier-than-thous and stuffed shirts and odd ducks and egomaniacs and milquetoasts and closet sensualists as are vividly represented here by you and me this spring evening. God is foolish to send us out to speak hope to a world that slogs along heart-deep in the conviction that from here on out things can only get worse. To speak of realities we cannot see when the realities we see all too well are already more than we can handle. To speak of loving our enemies when we have a hard enough time of it just loving our friends.

To be all things to all people when it’s usually all we can do to be anything that matters much to anybody. To proclaim eternal life in a world that is as obsessed with death as a quick browse through TV Guide or the newspapers or the drugstore paperbacks make plain enough. God is foolish to send us out on a journey for which there are no sure maps. Such is the foolishness of God.

And yet. The “and yet” of it is our faith, of course. And yet, Paul says, “the foolishness of God is wiser than men,” which is to say that in some unsearchable way he may even know what he is doing. Praise him.

If I were braver than I am, I would sing you a song at this point. If you were braver than you are, you might even encourage me to. But let me at least say you a song. It is from The Lord of the Rings, and Bilbo Baggins sings it. It goes like this.

The road goes ever on and on

Down from the door where it began.

Now far ahead the road has gone,

And I must follow if I can,

Pursuing it with weary feet,

Until it joins some larger way,

Where many paths and errands meet.

And whither then?

I cannot say.

“I am the way,” Jesus said. I am the road. And in some foolish fashion, we are all on the road that is his, that is he, or such at least is our hope and prayer. That is why we are here at this turning of the road. There is not a single shoe in this place that does not contain a foot of clay, a foot that drags, a foot that stumbles; but on just such feet we all seek to follow that road through a world where there are many other roads to follow, and hardly a one of them that is not more clearly marked and easier to tramp and toward an end more known, more assured, more realizable. But we have picked this road, or been picked by it. “I am the way,” he said, “the truth and the life.” We have come this far along the way. From time to time, when we have our wits about us, when our hearts are in the right place, when nothing more enticing or immediate shows up to distract us, we have glimpsed that truth. From time to time when the complex and wearisome and seductive business of living doesn’t get in our way, our pulses have quickened and gladdened to the pulse of that life. Who knows what the mysteries of our faith mean? Who knows what the Holy Spirit means? Who knows what the Resurrection means? Who knows what he means when he tells us that whenever two or three are gathered together in his name, he will be with them? But what at the very least they seem to mean is that there winds through all we think of as real life a way of life, a way to life, that is so vastly realer still that we cannot think of him, whose way it is, as anything less than vastly alive.

It’s a business that breaks the heart for the sake of the heart. It’s a hard and chancy business whose risks are as great even as its rewards. Above all else, perhaps, it is a crazy business. It is a foolish business. It is a crazy and foolish business to work for Christ in a world where most people most of the time don’t give a hoot in hell whether you work for him or not.

By grace we are on that way. By grace there come unbidden moments when we feel in our bones what it is like to be on that way. Our clay feet drag us to the bedroom of the garrulous old woman, to the alcoholic who for the tenth time has phoned to threaten suicide just as we are sitting down to supper, to the laying of the cornerstone of the new gym to deliver ourselves of a prayer that nobody much listens to, to the Bible study group where nobody has done any studying, to the Xerox machine. We don’t want to go. We go in fear of the terrible needs of the ones we go to. We go in fear of our own emptiness from which it is hard to believe that any word or deed of help or hope or healing can come. But we go because it is where his way leads us; and again and again we are blessed by our going in ways we can never anticipate, and our going becomes a blessing to the ones we go to because when we follow his way, we never go entirely alone, and it is always something more than just ourselves and our own emptiness that we bring. Is that true? Is it true in the sense that it is true that there are seven days in a week and that light travels faster than sound? Maybe the final answer that faith can give to that awesome and final question occurs in a letter that Dostoevski wrote to a friend in 1854. “If anyone proved to me that Christ was outside the truth,” he wrote, “and it really was so that the truth was outside Christ, then I would prefer to remain with Christ than with the truth.”

“The road goes ever on and on,” the song says, “down from the door where it began,” and for each of us there was a different door, and we all have different tales to tell of where and when and how our journeys began. Perhaps there was no single moment but rather a series of moments that together started us off. For me, there was hearing a drunken blasphemy in a bar. There was a dream where I found myself writing down a name which, though I couldn’t remember it when I woke up, I knew was the true and secret name of everything that matters or could ever matter. As I lay on the grass one afternoon thinking that if ever I was going to know the truth in all its fullness, it was going to be then, there was a stirring in the air that made two apple branches strike against each other with a wooden clack, and I suspect that any more of the truth than that would have been the end of me instead of, as it turned out, part of the beginning.

Such moments as those, and others no less foolish, were, together, the door from which the road began for me, and who knows where it began for each of you. But this much at least, I think, would be true for us all: that one way or another the road starts off from passion -- a passion for what is holy and hidden, a passion for Christ. It is a little like falling in love, or, to put it more accurately, I suppose, falling in love is a little like it. The breath quickens. Scales fall from the eyes. A world within the world flames up. If you are Simeon Stylites, you spend the rest of your days perched on a flagpole. If you are Saint Francis, you go out and preach to the red-winged blackbirds. If you are Albert Schweitzer, you give up theology and Bach and go to medical school. And if that sort of thing is too rich for your blood, you go to a seminary. You did. I did. And for some of us, it’s not all that crazy a thing to do.

It’s not such a crazy thing to do because if seminaries don’t as a rule turn out saints and heroes, they at least teach you a thing or two. “God has made foolish the wisdom of the world,” Paul says, but not until wisdom has served its purpose. Passion is all very well. It is all very well to fall in love. But passion must be grounded, or like lightning without a lightning rod it can blow fuses and burn the house down. Passion must be related not just to the world inside your skin where it is born but to the world outside your skin where it has to learn to walk and talk and act in terms of social justice and human need and politics and nuclear power and God knows what-all else or otherwise become as shadowy and irrelevant as all the other good intentions that the way to hell is paved with. Passion must be harnessed and put to work, and the power that first stirs the heart must become the power that also stirs the hands and feet because it is the places your feet take you to and the work you find for your hands that finally proclaim who you are and who Christ is. Passion without wisdom to give it shape and direction is as empty as wisdom without passion to give it power and purpose. So you sit at the feet of the wise and learn what they have to teach, and our debts to them are so great that, if your experience is like mine, even twenty-five years later you will draw on the depth and breadth of their insights, and their voices will speak in you still, and again and again you will find yourself speaking in their voices. You learn as much as you can from the wise until finally, if you do it right and things break your way, you are wise enough to be yourself, and brave enough to speak with your own voice, and foolish enough, for Christ’s sake, to live and serve out of the uniqueness of your own vision of him and out of your own passion.

“And whither then?” the song asks. The world of The Lord of the Rings is an enchanted world. It is a shadowy world where life and death are at stake and where things are seldom what they seem. It is a dangerous and beautiful world in which great evil and great good are engaged in a battle where more often than not the odds are heavily in favor of great evil. It is a world where enormous burdens are loaded on small shoulders and where the most fateful issues hang on what are apparently the most homely and insignificant decisions. And thus it is through a world in many ways much like our own that the road winds.

Strange things happen. Again and again Christ is present not where, as priests, you would be apt to look for him but precisely where you wouldn’t have thought to look for him in a thousand years.

You will be ordained, many of you, or have been already, and if again your experience is anything like mine, you will find, or have found, that something more even than an outlandish new title and an outlandish new set of responsibilities is conferred in that outlandish ceremony. Without wanting to sound unduly fanciful, I think it is fair to say that an extraordinary new adventure begins with ordination, a new stretch of the road, that is unlike any other that you have either experienced or imagined. Your life is no longer your own in the same sense. You are not any more virtuous than you ever were -- certainly no new sanctity or wisdom or power suddenly descends -- but you are nonetheless “on call” in a new way. You start moving through the world as the declared representative of what people variously see as either the world’s oldest and most persistent and superannuated superstition, or the world’s wildest and most improbable dream, or the holy, living truth itself. In unexpected ways and at unexpected times people of all sorts, believers and unbelievers alike, make their way to you looking for something that often they themselves can’t name any more than you can well name it to them. Often their lives touch yours at the moments when they are most vulnerable, when some great grief or gladness or perplexity has swept away all the usual barriers we erect between each other so that you see them for a little as who they really are, and you yourself are stripped naked by their nakedness.

Strange things happen. Again and again Christ is present not where, as priests, you would be apt to look for him but precisely where you wouldn’t have thought to look for him in a thousand years. The great preacher, the sunset, the Mozart Requiem can leave you cold, but the child in the doorway, the rain on the roof, the half-remembered dream, can speak of him and for him with an eloquence that turns your knees to water. The decisions you think are most important turn out not to matter so much after all, but whether or not you mail the letter, the way you say goodbye or decide not to say it, the afternoon you cancel everything and drive out to the beach to watch the tide come in -- these are apt to be the moments when souls are won or lost, including quite possibly your own.

You come to places where many paths and errands meet, as the song says, as all our paths meet for a moment here, we friends who are strangers, we strangers who are friends. Great possibilities for good or for ill may come of the meeting, and often it is the leaden casket rather than the golden casket that contains the treasure, and the one who seems to have least to offer turns out to be the one who has most.

“And whither then?” Whither now? “I cannot say,” the singer says, nor yet can I. But far ahead the road goes on anyway, and we must follow if we can because it is our road, it is his road, it is the only road that matters when you come right down to it. Let me finally say only this one thing more.

I was sitting by the side of the road one day last fall. It was a dark time in my life. I was full of anxiety, full of fear and uncertainty. The world within seemed as shadowy as the world without. And then, as I sat there, I spotted a car coming down the road toward me with one of those license plates that you can get by paying a little extra with a word on it instead of just numbers and a letter or two. And of all the words the license plate might have had on it, the word that it did have was the word T-R-U-S-T: TRUST. And as it came close enough for me to read, it became suddenly for me a word from on high, and I give it to you here as a word from on high also for you, a kind of graduation present.

The world is full of dark shadows to be sure, both the world without and the world within, and the road we’ve all set off on is long and hard and often hard to find, but the word is trust. Trust the deepest intuitions of your own heart. Trust the source of your own truest gladness. Trust the road. Above all else, trust him. Trust him. Amen.

“The Road Goes On” from “A Room Called Remember: Uncollected Pieces” by Frederick Buechner, copyright © 1984 by Frederick Buechner. Courtesy of HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Featured in Buechner 101: Essays and Sermons by Frederick Buechner (Frederick Buechner Center, 2016), available in paperback or Kindle edition from Amazon.com.