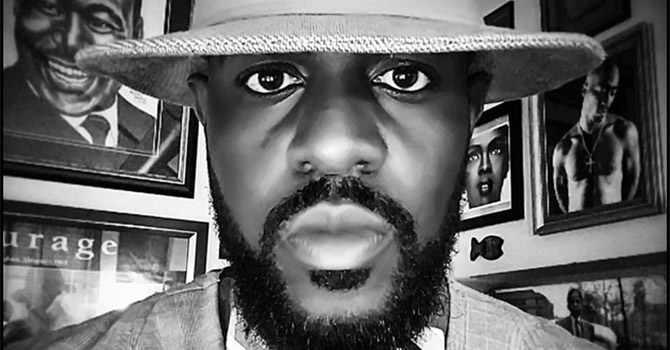

Mark Anthony Neal has a deal with his daughters, ages 17 and 21: whoever drives chooses the music.

He doesn’t always like what they listen to, but he recognizes the value.

The professor of Black popular culture at Duke University is adamant that any contemporary art should be analyzed in its own context rather than expected to sound or look the same as what might be familiar.

“It’s only in its own context that you get any value out of it to understand what the artists were attempting to address and articulate in this moment,” he said.

It’s important to “take off critical blinders,” Neal said, and appreciate what a voice is saying to its own time. Only by suspending the comfort zone of personal preference and judgment can one productively engage with contemporary culture, he said.

The principle of understanding before critiquing is especially pertinent to Christian leaders as the culture leans further away from organized religion. And hip-hop, as a genre that has been produced by a generation with less contact with the Black church than ever before, is a perfect example.

Neal is the chair of Duke University’s Department of African & African American Studies and the author of several books, including “New Black Man.” He teaches courses on pop culture, Black masculinity and the history of hip-hop, among other subjects.

He spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Chris Karnadi about the intersection between the Black church and Black music, the distance between hip-hop and the church, and how to learn productively from pop culture. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Where do you see the intersection between the Black church and Black culture?

Mark Anthony Neal: I think when you talk about Black music, the influence of the Black church, particularly Black church musical culture, is inescapable.

What we think of as early blues music was really nothing more than secular spiritual. When we think of the emergence of gospel music in the 1930s, it was really basically spiritual music with blues chords. And when you think about the emergence of soul music in the 1950s, it was really the coming together of traditional rhythm and blues and gospel music.

And the fact that so many of the iconic figures of soul music all literally came out of the churches -- in some cases, like Sam Cooke, literally came out of gospel groups -- that kind of connection is inescapable.

Even when you think about hip-hop, which doesn’t sound the way that we would typically think of gospel music, hip-hop artists have been raising questions for 40 years about where they are in the world, why they’re here.

You’ve got general questions about the experience and the existential aspects of Black life, and in that context, you see some aspects of spirituality, whether it be Christian faith or Islam or, in some cases, even Buddhism.

You have examples in Kanye West as someone who clearly has aligned himself with Christian practices. Someone like Chance the Rapper, I would argue, the same thing.

But for the more rank-and-file rappers, it’s really more a question of spirituality -- the belief in a higher God, a higher force, and the idea that part of their music is an attempt to connect with some sort of spiritual essence. I think many of their questions, they would argue, transcend formal religion, as more about a question of personal faith.

F&L: What do you think listening to hip-hop can actually teach us about church, or specifically, Black church?

MAN: I’m not sure hip-hop artists would necessarily argue what I’m about to say themselves -- but they are part of a tradition of Black oratory culture.

In that regard, if you think about the performance in hip-hop, it’s not a large stretch to think about audiences at hip-hop performances as a congregation in that sense.

I think if there’s something to be learned about at least the role of the Black church in 2020 via hip-hop, it’s that we’re probably looking at the first generation of Black youth who did not come up explicitly within the context of Black church culture.

Lots of reasons for that, including a general mistrust of religion, but I think when you see this kind of disconnect, you really have the first generation of Black artists who weren’t explicitly raised in the church. I think that’s a commentary in and of itself on the role that the Black church plays or doesn’t play in this moment for Black youth.

And a lot of that comes down to questions around LGBTQ identity and the fact that the Black church has been particularly conservative around issues of gender and sexuality. You have a generation of Black folks, regardless of even their political beliefs, kind of pushing past these very rigid notions of Black identity.

I always thought it was particularly interesting, when Jay-Z very publicly came on board to support then-President Obama’s belief in same-sex marriage, that no one would have ever predicted 20 years earlier that hip-hop would be right on the LGBTQ question before the Black church was.

F&L: What do you think the relationship is between activism, pop culture and religion?

MAN: The activism piece is interesting in this moment because I think for a lot of artists, their activism is connected so intimately to their brand. So if you’re an artist who represents a certain kind of brand that aligns with certain kinds of political views, it’s much easier -- and actually lucrative -- to do that now than it was five, 10, 15 years ago.

I’m typically more drawn to artists who have still maintained some sort of grassroots relationship with their communities and whose politics flows out of those grassroots relationships.

This is not to say that I don’t appreciate the work of, say, Chrissy Teigen and John Legend or that I don’t appreciate the very kind of bourgeois politics that we see from a Jay-Z or Beyonce.

Part of the thing that made people so drawn to Nipsey Hussle when he was alive, and I would argue even more so since his death, is that this was someone who was independent and on the margins of the mainstream, but the fact is he still committed so much of his energy and his financial resources to the very communities that he grew up and lived in.

My colleague Jon Caramanica has talked about the fact that Nipsey Hussle and others like 9th Wonder are what we call middle-class rappers -- guys who aren’t living so high up on the food chain. They’re not living in the ’hood, but they’re still what I might describe as ’hood tangential.

There’s still very much a vibrant economic and spiritual and community connection to these working-class communities that they came from, and so their activism, I think, resonates even more powerfully in that case, because folks really see them on an everyday basis.

There’s an artist who comes out of Pittsburgh named Jasiri X, and Jasiri X came up as a minister in the Nation of Islam. He actually left the Nation a few years ago, but he also became an activist and got very involved in different national foundations and has consistently over the last 15 years done very astute and politically charged hip-hop music -- nothing that’s ever bubbled into mainstream.

At the same time, he’s created these organizations in Pittsburgh like 1Hood, which is an organization that basically helps train sixth through 12th graders in media and literacy.

So they’re not only producing original content that counters media narratives about Black youth; they’re also training young folks to be able to read some of the disruptions and misrepresentation being circulated in the culture about Black youth.

F&L: What are some practices that people could have to engage with pop culture productively?

MAN: I think one of the things is that you take off -- I don’t want to say moral blinders, but you take off critical blinders.

Part of the argument that I often have with people of my generation and folks who are older than me is the desire to place their own musical values and cultural values on what’s being produced by a younger generation of artists, whether hip-hop or any other kind of musical genre or cultural genre.

I think it’s important that if you’re going to judge any contemporary art, it has to be judged within the context and the values of the artist that produced it and the historical moment that it’s produced in.

It does no one any good to look at an artist like Lizzo and attempt to read Lizzo the same way as Aretha Franklin -- very, very different, distinct historical, cultural and social realities. To understand Lizzo, you have to understand her in the context that produced her now.

I think that’s a little difficult, because we get very complacent and comfortable. We like what we like, and we’re drawn to things that make us feel comfortable about who we are and where we come from. The really productive way of engaging popular culture comes from being able to suspend that comfort zone to get a better sense of what’s going on.

It’s something I feel personally on a fairly regular basis. I have a 21-year-old daughter who listens to what I listen to and a 17-year-old daughter who also listens to what I listen to, but also listens to a bunch of stuff that I have no interest in. We have a deal: whoever is behind the wheel of the car gets to dictate the music that’s being played.

So when [the 17-year-old] is driving, I’m listening to a lot of this mumble rap and other stuff, and what I find is that some of this stuff, if you actually sit down and listen to it in the context in which it’s made, it’s actually really powerful stuff these young folks are trying to articulate about their lives.

But it’s only because I was willing to suspend my own judgment about what this music is and what it sounds like and what its value is that I was able to hear something particularly compelling about it.