On the blackboard of our classroom I wrote a single sentence:

“Think of ministry in the midst of conflict as follows: the negotiation of difference for the sake of transformation.”

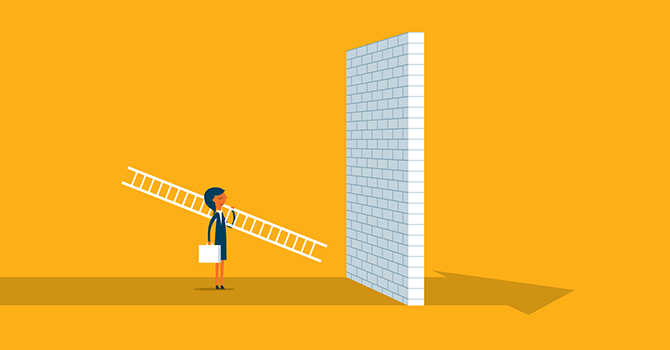

The point is obvious to any veteran pastor, though it is extremely difficult to put into action. If you think of conflict as something to be resolved, you may be tempted to try to return to some elusive past. If you think of conflict as something to be managed, you may be tempted to try to maintain the status quo. But if you think of conflict as (at least potentially) an opportunity for transformation, you are liberated to explore what it means to negotiate differences of perspectives, values and interests as a genuine spiritual discipline in your church.

I believe, with John Calvin, that “in all of life we have our dealings with God,” so there’s no part of life that shouldn’t be subject to theological reflection, and there’s no theological reflection that can’t also be informed by social, historical, psychological and other kinds of inquiries. I also believe, with John Stuart Mill, Lewis Coser and Nicholas Rescher, that differences and conflicts among people (if handled well) are potentially creative and transformative. Rather than avoiding conflict, we ought rather to “make the world safe for disagreement,” as Rescher once wrote.

One only has to look at the lives of the all-stars of the saintly world, from St. Paul to Mother Theresa to see that spiritual growth is not conflict-free.

I was struck recently by a statement in The New York Times in a story about a church experiencing a conflict, the specifics of which are not relevant to these reflections. A church member said, “I came here looking for a church for spiritual reasons… but it has really not been a very spiritual experience.” This person’s comment could be replicated all over the country, in various churches, by people belonging to any number of denominations. He assumes that a spiritual experience is happy and ethereal; certainly it is non-political, untouched by human interests, unsullied by conflict.

I once heard a distinguished biblical scholar dismiss the Nicene Creed because the council that gave rise to it was tainted by politics. This was not simply naïve. It also represented an inadequate understanding of the Holy Spirit. The same God who got his hands dirty in the incarnation continues to work through human means to accomplish redemptive purposes in the world.

This is nowhere more true that at the ground level of transformation among ordinary Christians in ordinary congregations. God transforms us, not despite, but through living with others who are (often!) a royal pain in the posterior regions.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: we grow precisely in those moments when previous assumptions are tested and we experience cognitive dissonance. We mature precisely at those points where we have to move beyond clarity and into the realm of ambiguity. We are transformed when our hopes die and we witness God’s hopes standing in their place on the other side of Good Friday’s cold tomb. Real spirituality, sooner or later, leads us through the crucible of conflict.

Transformative ministry can’t run from conflict, but needs to find ways to minister through conflict, bearing witness to Jesus Christ who entreats us to be merciful so that we can be recognized as children of a merciful God.

Michael Jinkins is dean and professor of pastoral theology at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary, Austin, Texas.