The church is stuck in a war between “We’ve always done it that way” and “The future is about leading change.”

Consider worship. In response to those ritual fundamentalists who insisted that nothing (especially music) change, innovators created “contemporary” worship services. But those services became so unfamiliar that people now long for opportunities to sing the “old familiar” contemporary songs, such as “Lord, I Lift your Name on High.”

In businesses and other organizations, including Christian ones, the traditionalists are so stuck in their ways that they drive reasonable people toward change for its own sake. People obsessed with change create such chaos that reasonable people long for some form of stability. And so the pendulum swings between traditionalist strategies and innovative ones, causing organizations and leaders, people and cultures, to suffer.

It is a return to Christian thinking that offers the best way forward.

A colleague and friend who studies social entrepreneurship helped me come to this conclusion. He wondered why, over the course of the last couple of centuries in America, the best socially entrepreneurial organizations had consistently been faith-based, especially if they developed significant scale and scope. He had in mind organizations such as Goodwill, Salvation Army and Habitat for Humanity. He was thinking of faith-based hospitals, schools and, more recently, hospice organizations. Only in the last 25 years, he noted, had social entrepreneurship become relatively secular. What has happened in the church?

His question got me reading about social entrepreneurship, a relatively new area of scholarship and study in business schools. Amid a lot of ideas that had Christian resonance, I was struck by an emerging debate about “newness.” Can an existing organization do social entrepreneurship, or does it always require a new structure? It seemed to be a misplaced debate to me -- after all, Christian organizations and churches have long engaged in innovation within our existing structures. We have typically called it bearing witness to the Holy Spirit, the One who is “making all things new.”

Christian leaders are called to a particular type of social entrepreneurship -- one that does not force us to choose preserving tradition or leading change, but thinking about them together. We are called to “traditioned innovation” as a pattern of thinking, bearing witness to the Holy Spirit who is conforming us to Christ. I asked a New Testament scholar what came to mind when he heard that phrase. He said, “The New Testament. Indeed, the whole of Scripture.” The best way to interpret the book of Acts, or Paul’s account of Sarah and Hagar in Galatians, is a process of discernment rooted in traditioned innovation. How do we integrate the transformative work of Christ into our ongoing identity as the people of God rooted in biblical Israel’s calling?

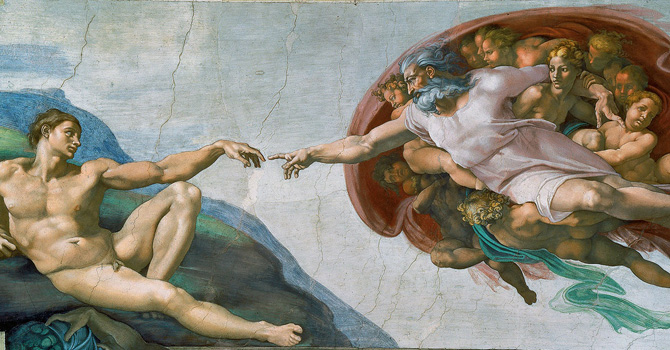

In our thinking as well as our living, we are oriented toward our end, our telos: bearing witness to the reign of God. That is what compels innovation. But our end is also our beginning, because we are called to bear witness to the redemptive work of Christ who is the Word that created the world. We are the carriers of that which has gone before us so we can bear witness faithfully to the future.

Tradition is fundamentally different from traditionalism. Jaroslav Pelikan, in “The Vindication of Tradition,” characterized the difference when he wrote, “Tradition is the living faith of the dead; traditionalism is the dead faith of the living.” People who bear a tradition are called to be relentlessly innovative in ways that preserve the life-giving character of the tradition.

We need not rely only on patterns within Scripture, or even the practices of the church, however, to appreciate the significance of traditioned innovation as a way of thinking. Biologists such as Marc Kirschner and John Gerhart, in their “The Plausibility of Life,” have compellingly argued that organisms must preserve significant features of their processes while changing others. A great surprise of modern biology, they suggest, has been how important conservation is to the process of adaptive change.

So also with institutions. We do not need radical change. The task of transformative leadership is not simply to “lead change.” Transformative leaders know what to preserve as well as what to change. We need to conserve wisdom even as we explore risk-taking mission and service. Too much change creates chaos. Transformative change, rooted in tradition and the preservation of wisdom, cultivates the adaptive work that is crucial to the ongoing vitality and growth of any organism, Christian institutions included.

Sometimes that will mean we innovate within existing institutions; at other times we will allow some forms to die so that other ones can rise up in their place. And at still other times we will give birth to new forms to address challenges and opportunities. But even our most dramatic transformations ought to be tethered to our most life-giving past.

There are few things we have “always” done in any particular way, and there are even fewer things that we want “always” to change. Perhaps we can do better than a cease-fire in these culture wars. Instead, transformative leaders should adopt traditioned innovation as a pattern of thinking that will help cultivate thriving communities. It would be a welcome change.