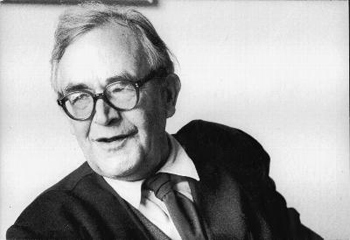

I knew Karl Barth was a monumental figure who shifted the gears of Christian theology in the 20th century, but I did not know until recently that he was also a father who buried a son.

Robert Matthias Barth, 20, was mountain climbing in the Swiss Alps when he fell to his death on June 21, 1941. Four days later, Karl Barth preached at his memorial service in Bubendorf, where his oldest son was pastor.

The story of Matthias’ death and the sermon his father preached humanized a theological giant for me. Barth became one of us -- a brokenhearted parent, whose grief was framed by a faith that was big enough to encompass the pain of every parent who has ever lost a child.

I discovered Barth’s sermon in one of those bouts of homiletical desperation that confront any preacher who attempts to offer a word of honesty and hope while standing beside the casket of a person who died too young. It was one of those senseless deaths that can make us bitter or make us better, the kind of shattering loss that either undermines our faith or undergirds it.

Greg was 31. He and his wife were approaching their first wedding anniversary when he was diagnosed with cancer. His son was born two months before he died. Greg’s mother is our organist and choir director.

In his sermon, Barth focused the congregation’s attention on Paul’s use of the words “now” and “then” in 1 Corinthians 13. “For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known. And now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; and the greatest of these is love” (NRSV).

Barth said that both are “deeply and indissolubly united with each other: the Now! but also the Then!” Speaking of Matthias’ death, he said, “We ... stand with [Christ] at the border where the Now and the Then touch each other.” The translation in “This Incomplete One,” a book of sermons for people who died young, consistently capitalizes Now and Then.

With no illusion that Greg’s largely irreligious friends knew or cared about Karl Barth, I used his words to frame the way we stood at that border between Now and Then on the morning of his death. The doctors had done their best. The cancer had done its worst. The machines were silenced, the tubes withdrawn. The struggle was over. Greg had crossed over the inescapable and seemingly impenetrable boundary between life and death.

The only place to begin was with the awareness that “Now we see in a mirror, dimly; … now we know only in part.” There’s so much about Greg’s death we don’t know and can’t understand. There are so many questions we want to ask, don’t know how to ask, or are afraid to ask.

I’m more than a little skeptical about well-intended people who offer simple answers or easy clichés for deaths like these. I’m grateful for the way Eugene Peterson paraphrased Paul’s words: “We don’t yet see things clearly. We’re squinting in a fog, peering through a mist.” That’s just how things are Now, on this side of the border.

But the Scripture points beyond Now to the promise of Then. On the other side of resurrection, we shall see face to face. Then we will understand fully, even as we have been fully understood. Peterson paraphrased it: “It won’t be long before the weather clears and the sun shines bright!”

Now we stand in the darkness of grief. Then we will walk into the sunlight of resurrection. Now we feel the ghastly separation of death. Then we will know the fullness of life in Christ.

Paul named three essential qualities that link our Now with God’s Then. They are faith, hope and love.

We stand at the border with faith that dares to believe that the voice within us that cries out, “This isn’t right! This isn’t fair! This isn’t the way things should be!” is nothing less than the Spirit of God crying within us with groans too deep for words (Romans 8:26).

There are always well-meaning, sincere folks who find comfort in saying, “God must have had a reason for this.” They talk as if God micromanaged Greg’s cancer the way Greg micromanaged the arrangement of his shirts in his closet, every one in perfect order.

But it just won’t carry the freight. What kind of God would micromanage a mountain climber’s fall? What kind of God would tear apart a young marriage and rob a two-month-old son of his father?

I’d rather place my faith in the God who announced his intention for this world through Isaiah:

I will rejoice in Jerusalem,

and delight in my people;

no more shall the sound of weeping be heard in it,

or the cry of distress.

No more shall there be in it

an infant that lives but a few days,

or an old person who does not live out a lifetime;

for one who dies at a hundred years will be considered a youth; …

for like the days of a tree shall the days of my people be,

and my chosen shall long enjoy the work of their hands.

(Isaiah 65:19-22)

In Greg’s service I proclaimed the good news of the God for whom death is not a friend to be accepted but an enemy to be defeated, the God who breaks through the boundary between Now and Then.

We stand at the border with hope. It’s hope that “as in Adam all die” (that’s how it is Now), “so in Christ shall all be made alive” (that’s how it will be Then).

Under Greg’s mother’s direction, the chancel choir sang a magnificent arrangement of Isaac Watts’ lyrics in the memorial service:

There would I find a settled rest,

While others go and come;

No more a stranger, nor a guest,

But like a child at home.

Our hope is that when we cross the border between Now and Then, we enter into the presence of God, not as a stranger, or even as a guest, but as a child at home.

Barth expressed that confidence when he said, “In our thoughts about our Matthias we do not want to put ourselves in any other place than precisely at this border. He has now crossed over it, and we are still here. But we are not far from each other if we put ourselves at this border.”

Above all else, we stand at the border with love that overcomes the separation between Now and Then. Barth’s words became a personal witness of the persistent dialectic in his theology:

It is by the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ that the Now and the Then are together in such a way that no power in heaven or on earth can separate them again. ... [We] stand with him at the border where the Now and the Then touch each other.

… It is at this border where light falls into darkness, where life always rejoices in the face of death, where we are great sinners yet righteous, where we are taken captive yet free, where we see no way out yet we have hope, where we have doubts yet we are certain, where we weep yet we are glad.

We saw the love of God in Christ made flesh in the days leading up to Greg’s death; in the friendships that surrounded him; in the courage with which his wife mother and brother confronted the sinister power of cancer; in the congregation that supported them along the way. All of these were finite expressions of the infinite love of the God who loved Greg before he was born, claimed him in his baptism, walked with him through his life and finally welcomed him like a child at home on the other side of the border between Now and Then.

I remembered Greg’s love for the Florida sun when I read Barth’s words about Matthias: “We no longer see him and the astonishing things about him, because he walked straight into the beaming ray of the resurrection of his Lord and ours.”

Acknowledging the very real pain of his son’s death, Barth concluded with a ringing affirmation of faith: “The Then has come so close to the Now so that this Now of death is no longer a special realm of which we have to be afraid. … We see that death has power, terrifying and painful power. But we believe and we know that it does not have a deadly sting.”

And so we face every painful Now in confident hope of God’s Then.