Congregations courageous enough to talk openly about money are more likely to see their revenue streams grow than those that treat the topic as taboo, according to the recently released National Study of Congregations’ Economic Practices, the largest nationally representative survey of congregational finances in a generation.

The study, conducted by the Lake Institute on Faith & Giving at the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at IUPUI, examined the practices of receiving, managing and spending financial resources in 1,231 U.S. congregations between 2014 and 2017.

Among the study’s key findings:

- Higher percentages of black Protestant congregations reported growth in participation (62%) and giving (59%) over the three-year period than any other group.

- With respect to generational age, congregations with majorities of baby boomers and Gen Xers reported the greatest growth in revenue, while the few congregations with majority millennials (2%) were the most likely to experience decreases in size (74%) and revenue (68%).

- The newest congregations -- those established after 2000 -- reported the most growth in both size and revenue, with 66% reporting increases in membership and 69% reporting increases in revenue.

- Thirty-five percent of congregations reported a decrease in revenue over the study’s three-year focus period, with more Catholic (56%) and mainline Protestant (38%) congregations noting that trend than others.

Forty-eight percent of respondents reported an increase in revenue between 2014 and 2017, even though only 39% reported an increase in membership.

But significantly, that revenue growth was more prevalent among congregations that regularly discussed the theological importance of giving, whether through biblical passages, sermons or personal testimonies.

Though many clergy remain squeamish about addressing finances with their congregations, those who do can help promote healthy economic practices among members, and a culture of generosity within the congregation, said study co-author David P. King, the Karen Lake Buttrey Director of the Lake Institute on Faith & Giving.

“They’re releasing the power of money in the organization when they’re unwilling to let it be a taboo or silent topic,” King said.

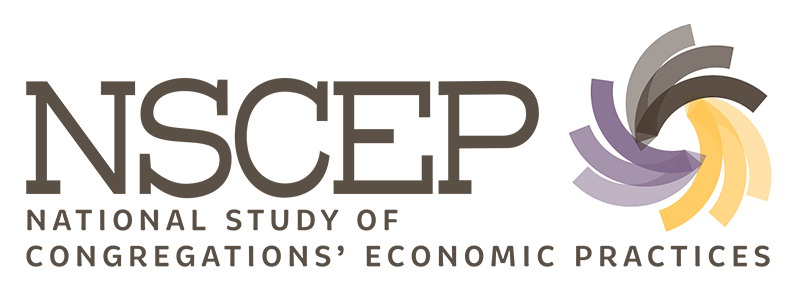

According to the study, though the vast majority of congregations appealed for money weekly during religious services, primarily by passing a collection plate, only 9% of them actually set aside time each week to teach or preach about giving. Of that 9%, 90% reported an increase in revenue between 2014 and 2017.

That pattern held as well for congregations that broached the subject less frequently.

Of the 12% of congregations that said they addressed the issue monthly, 73% reported increases in revenue.

Of congregations that discussed it only once a year, 44% experienced an increase in revenue, and the proportion fell to 16% among congregations that said they never discussed giving.

The study notes that teaching on giving need not be limited to religious instruction about where, when and how much to give. Instead, congregations can roll that into larger conversations about materialism, consumer culture and responsible money management.

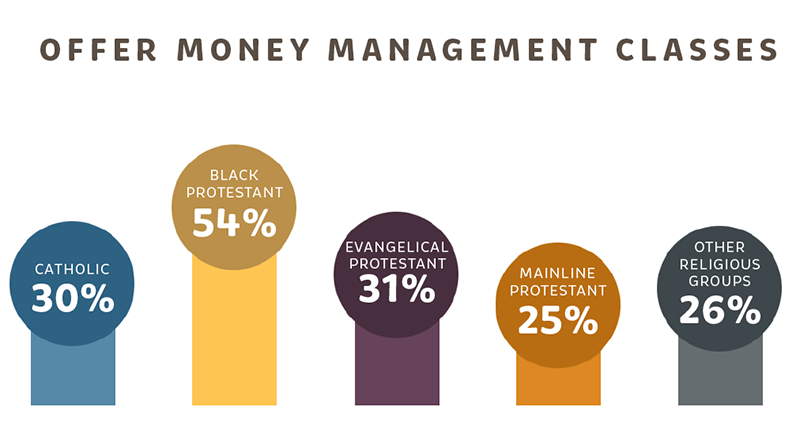

For instance, King said, 31% of congregations reported offering groups or classes focused on personal finance -- a prime opportunity to explore principled economic strategies, including charitable giving. Black Protestant congregations led the way in this regard, with 54% offering this service, according to the study.

A larger proportion of black Protestant congregations -- 59% -- also experienced an increase in revenue between 2014 and 2017, more than the evangelical Protestant (51%), mainline Protestant (48%), Catholic (31%), or “other” congregations (53%), a category encompassing a variety of world religions, including Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu and Unitarian.

“A first place to start would be not to talk so much about what to give or how much to give with people in the pews but have broader conversations about the meaning of money -- how it makes us feel, our experiences with it, our barriers to giving, getting people to tell their stories, testimonies in worship services,” King said.

“When it shows up in the lectionary, don’t avoid it. Bring those questions to bear in service. People are primed and ready to give. We just need to give them avenues to give on-mission.”

While congregations continue to receive the largest percentage of charitable giving in the U.S., 29% of all such giving ($125 billion in 2018), that’s down from 50% in the 1980s, according to the study, which was funded by a $1.67 million grant from Lilly Endowment Inc.

A fluctuating economy, a decrease in the number of households giving to charity, and an increase in the number of nonprofit organizations competing for that money have all contributed to the drop. More than ever, congregations need to make the case for why they are the best stewards of charitable giving, King said.

That can be especially challenging for clergy who may be uncomfortable diving into a congregation’s finances, a topic not necessarily covered in seminary.

While the leader of a large nonprofit organization would be expected to know who its major contributors are, only 55% of congregations in the study reported that the head clergyperson had access to participants’ giving records. And among those congregations, only 58% said the clergy actually looked.

Those who reported not looking cited the potential for preferential treatment or influence based on how much individuals gave. Yet among those congregations where clergy said they did look at donation records, 58% reported an increase in revenue over the three-year period of the study -- with 42% noting an increase of 10% or more.

“Can you imagine the executive of a major nonprofit not knowing who their major donors are?” King said. “We’re squeamish to talk about money, so we don’t know what’s going on in our organization. But the time for being humble and shy in making your case is over. The time for talking about money as if it’s taboo in a congregation should also be over.”

Interestingly, the practice of passing the collection plate during weekly worship services is still the primary way congregations collect revenue. According to the study, 81% of congregational funding comes from individual donations, with 78% of those donations coming weekly during worship services.

While 40% of congregations said they relied on those individual donations for nearly all their revenue, others reported raising money through special fundraisers, like bingo and bake sales, renting out facilities, collecting program fees, and so-called “passive income,” like investments, endowments or bequests.

Roughly 72% of all the money raised was spent on personnel and facility costs, while the rest supported programming (10%) -- with the largest chunk of that (35%) spent on worship needs -- and mission or outreach efforts (11%), which ranged from food and clothing donations to disaster relief and substance abuse counseling. Researchers will delve more specifically into congregations’ service work as part of a spin-off study, King said.

In addition, they intend to conduct face-to-face interviews with 100 of the clergy who participated in the original study to examine more specifically how their congregations regard money from a theological, cultural and practical perspective, he said.

Questions will include how often those clergy preach about giving, what texts are used in the process, and whether clergy have avoided preaching on a topic for fear it would negatively impact giving.

Dustin Benac, a member of the research team and a doctor of theology candidate at Duke Divinity School, recently conducted 17 interviews with pastors up and down the East Coast. He said he hopes that marrying the quantitative data gathered during the first phase of the research with the qualitative stories shared during the second phase will prove illuminating for congregations seeking to strengthen their finances.

“In talking to pastors, they’re hungry for this type of material,” he said.

For now, said King, there’s no one right way to attract, manage and spend revenue within a congregation, and any changes adopted in the wake of the study should be sure to keep the congregation’s existing culture in mind.

For instance, in this day and age, having a digital tool for giving can be helpful. But if the pastor has spent months railing against screens, then introducing an app or a text-to-give option may not be an immediate financial game changer.

King stresses that religious leaders don’t need an MBA to discuss finances with their congregations.

“You may feel you’re underprepared to read a balance sheet or understand investment strategies, but you’re well-equipped to be a leader,” he said. “Building relationships through conversation, tackling tough topics, knowing how to lead an organization around deeper cultural questions -- that’s what clergy do well. So remember those skills you have.”