Editor’s note: Allan Hugh Cole Jr. delivered his inaugural address as academic dean on March 7, 2011, at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. The address, excerpted below, was adapted from Cole’s latest book, “A Spiritual Life: Perspectives from Poets, Prophets, and Preachers.”

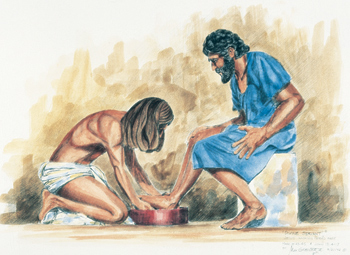

I sometimes sit at my campus desk and ponder a painting that hangs above it. The painting depicts Jesus washing Peter’s feet as described in the Gospel of John (13:1-15).

I find this story simultaneously beautiful and challenging, which I suppose is the point. Beautiful because of Jesus’ tender care for those he loves; he washes the feet of many disciples on this occasion, a humble and generous act. Challenging because he tells Peter and the rest who profess to follow him to go and do likewise to others: “For I have set you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you” (John 13:15 NRSV).

I’ve long thought that this story sums up the Christian life. Perhaps it sums up the spiritual life as well.

Looking at the painting, with water flowing over a washbasin onto the floor and Jesus on his hands and knees washing Peter’s dirty feet, I remember how Peter resisted Jesus’ offering. I also think about my own resistances that hamper my following Jesus. My thinking then turns to the spiritual life.

I have observed that when people speak of this life, they describe it in various forms and with a range of emphases.

People talk about the spiritual life in terms of a desire to live in closer relationship to God. They muse about life’s meaning and purpose, and the human values that follow. Sometimes they speak in terms of wanting more insight or wisdom regarding this or that problem or option. For some, a desire for healing and a newfound inner or relational peace remains bound to their views of a spiritual life.

Whatever the specifics, however, I often sense that when people speak about the spiritual life, they have in mind a kind of life notably different from a life absent the spiritual, and sometimes a life at least somewhat different from the one they currently live.

I also get a sense that whatever the spiritual life is to them, it’s important. So I want to know more of what they know about this life and certainly to gain knowledge that comes by way of their experiences; I want to hear their stories. In this way, I am spiritually hungry.

I say all of this only to add that despite my best efforts, I admit to knowing less than I’d like to know about the spiritual life: what it is, what marks it, how to cultivate it, and what gets in the way of it. My lack of knowledge becomes most apparent when the descriptive term “spiritual” becomes a catchall, genre term with little or no specificity, which seems a rather common way of using it. For example, people say, “I’m spiritual, but not religious.”

Truth be told, the closest I come to knowing about the spiritual life happens when I appeal, not to the general category of “the spiritual,” but rather to a particular Spirit -- the Holy Spirit of Christian faith and life.

I claim no uniqueness here. For more than two millennia, Christians have derived “the spiritual” from the Spirit -- at least they have at their best.

I also don’t pretend to understand this Spirit any more than I understand the spiritual life.

And when I hear people convey confidence in their knowledge and experience of the Holy Spirit, well, I get nervous. This is my problem, not theirs (and maybe not yours either). But when I hear “Spirit talk,” I usually hark back to a high school friend who caught fire for Jesus and wanted others to ignite, too, or to earlier childhood experiences with a Pentecostal distant cousin. His self-proclaimed Spirit-filled life scared the wits out of me and sent me running for nonspiritual sanctuaries for too many years. I still avoid people who make similar proclamations.

I also usually assume that confident talk of the Holy Spirit will fairly soon be overly sentimental, if not self-indulgent. I worry especially when the Holy Spirit becomes a cipher for propping up oneself and one’s own desires and ambitions -- such as when people say things like, “The Spirit is leading me to this decision” or “The Spirit spoke to me.”

Honestly, in my experience at least, Spirit talk too easily fosters an ethos akin to one created by a popular, antiphonal cheer at ballgames when I was in high school: “We got spirit, yes we do; we got spirit, how ’bout you?”

‘One short of a Trinity’

My tacit suspicions about Spirit talk were pointed out to me in 1994, my last year of seminary. A close friend and neighbor, the late Michael Girolimon, had the honors. Mike was working on his Ph.D. at Princeton Seminary when I was completing my master of divinity there.

I was preparing for ordination in the Presbyterian Church. I crafted a required statement of faith to read when examined by my presbytery, and I asked Mike to read it. A kind and thoughtful soul, he consented.

He read it with care and offered suggestions on how to improve it, structurally and stylistically. He also made an observation that called for more substantive editorial work. “It’s a good statement, Allan,” he said, “of a Binitarian.”

Assuming he was simply showing off with Ph.D. words, I asked what he meant. He said, “You fail to mention at all the Holy Spirit. You do just fine with God and Jesus, but you’re one short of a Trinity.”

The fact that he was raised a Pentecostal does not mean that he was wrong. In fact, he was right. That experience prompted me to work harder to become a Trinitarian.

I still work at this, but I got ordained and I’ve come a long way with the Spirit since then.

At the same time, being in some measure a Calvinist, I also know that old habits die hard.

I think the 20th-century theologian Karl Barth was right, nonetheless, in urging that we recognize and honor God’s transcendence -- God’s “wholly otherness” -- by not presuming that we know all that much about this God directly. Somewhat ironically, Barth went on to write tens of thousands of pages about this unknowable God. That he did so does not undermine his point, one that needs stressing today in North American Christian circles, especially when talk turns to spirituality.

One mark of Christian spirituality as commonly conceived of these days is that one can encounter God directly, tap the divine for all manner of needs, and (almost, it would seem) even snuggle up to God for a friendly back rub if need be.

Sometimes this way of relating to God gets framed in terms of one’s “personal relationship” with God -- a relationship seemingly cultivated as readily alone in a coffeehouse as in a house of worship with others. Other times it gets framed in terms of God’s being “everywhere” and “in everyone and everything.” Sometimes the way one relates to God gets expressed between these two relational poles.

But for Barth, and for me, what we know about God comes to us in Jesus, and we do well to look first to his life as we seek to know God most fully. We also do well to look to him to know more about the spiritual life. If Barth is correct, we also do well to tread lightly when presuming to know the Holy Spirit.

So, on my better days, I work to create space for this Spirit in my life -- in my story -- which unfolds against the backdrop of the Christian story that deeply influences how I live.

On my better days, I want that Spirit to shape and lead my life -- and more than that, to place boundaries around it -- which Jesus said happens among those who seek to follow him.

For me, this shaping and leading occur especially in prayer, worship, Scripture reading, service to others, and when playing with my children, among other ways, but always indirectly and never in a way that makes me catch fire. Thanks be to God.

So when I think of the spiritual life, I’m back to where a Christian life formally begins: baptism. …

‘The burden of the Gospels’

In “The Way of Ignorance and Other Essays,” Wendell Berry writes of living (for the most part willingly) “under the influence of the Bible, particularly the Gospels, and of the Christian tradition in literature and the other arts”; and he states that he is “by principle and often spontaneously, as if by nature, a man of faith.”

He makes this admission right after noting that “anybody half awake these days will be aware that there are many Christians who are exceedingly confident in their understanding of the Gospels, and who are exceedingly self-confident in their understanding of themselves in their faith.” Berry has a different perspective.

He writes:

[M]y reading of the Gospels, comforting and clarifying and instructive as they frequently are, deeply moving or exhilarating as they frequently are, has caused me to understand them also as a burden, sometimes raising the hardest of personal questions, sometimes bewildering, sometimes contradictory, sometimes apparently outrageous in their demands. This is the confession of an unconfident reader.

So Berry remains intentionally modest with regard to what he claims to know about his faith, which always involves loads of questions and concomitant burdens that “are not solvable but can only be lived with as a sort of continuing education.”

He then describes “the burden of the Gospels” -- namely, that if we read them in a way that leads us to take them seriously, then our lives get changed, often in ways that seem to bring as much discouragement as affirmation, as much cost as reward.

The same is true for the spiritual life, it seems to me, and especially when this life begins with and remains tethered to the baptized life. In saying this, I recognize that this way of viewing the spiritual life offers nothing new. Lodged in a pre-modern worldview and way of living, this view of the spiritual life may struggle to find its place among postmodern sensibilities, many of which I welcome and embrace.

But this is what I can say about the spiritual life: it links to a life in which one seeks to follow Jesus, and that life begins, at least formally, in the waters of baptism. About the spiritual life I can say nothing more or less.

I should add, too, that I envy those who know more definitively what the spiritual life is and, more importantly, who confidently (but not overconfidently) live it in more innovative ways. More power to them.

I’ve discovered, however, that I come closer to understanding and, on my better days, to living more of a religious life than a spiritual one.

I find religion less nebulous than spirituality, particularly when grounded in a set of religious practices -- those that give concrete expression to beliefs, values and purposes tied to the religion.

Right-brained though I am, I struggle with the abstractness of “the spiritual,” which, for me, can quickly dissolve into the disembodied ether before it ever hangs around long enough for me to encounter it in any fleshy sort of way.

I need these kinds of encounters, which is probably why I need to stare at Jesus washing another person’s feet.

Adapted from A Spiritual Life: Perspectives from Poets, Prophets, and Preachers . © 2011 by Allan Hugh Cole Jr. Used by permission of Westminster John Knox Press.