Editor’s note: To learn more about the Clergy Health Initiative, please visit its website.

North Carolina’s United Methodist clergy have higher rates of diabetes, arthritis, high blood pressure, angina and asthma than do comparable people in the state, according to a new study published in Obesity, the journal of the Obesity Society.

The study is the first to compare the health of a group of clergy with a similar group in the overall population. Although the data is limited to actively serving North Carolina United Methodist clergy, the results could be instructive for clergy in other denominations and other parts of the country as well.

The study was conducted by the Clergy Health Initiative, a $12 million, seven-year Duke Divinity School program funded by the Rural Church program area of The Duke Endowment.

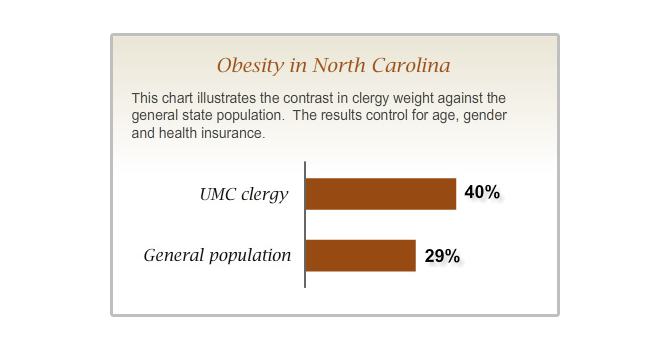

Much of the reason for declining clergy health is related to their increasing waistlines: Nearly 40 percent of North Carolina’s United Methodist clergy are obese, a designation given to individuals who have a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher. By comparison, the average North Carolinian in the study fares much better -- only 29 percent of North Carolinians are obese. Furthermore, only 25 percent of clergy, and 30 percent of North Carolinians, are of normal weight: that is, neither overweight nor obese.

This study builds on previously published results that looked at the complex web of relationships that have repercussions for pastors’ vocation and health.

“We now know how bad the state of clergy health really is,” said Robin Swift, the Clergy Health Initiative’s director of health programs.

Questions to consider

Questions to consider:

- How can we reach beyond solving these problems at the level of individuals’ behavior? Are there policy changes that might improve pastors’ health?

- Do you think that the way ministry is practiced in mainline denominations in the 21st century contributes to poor health? Why or why not?

- If you could propose ways to make clergy healthier, what would you suggest?

“A wake-up call”

Historically, clergy have lived longer than the average person, said Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell, the Clergy Health Initiative’s research director. She is the lead author of the study, with Sara H. LeGrand, a research scholar at the Duke Center for Health Policy.

But this may not last.

“I usually get a chuckle when I explain to pastors why their mortality rates are lower -- clergy have fewer accidents, fewer incidents of suicide and, well, they just aren’t prone to syphilis,” Proeschold-Bell said. “But churches are having an increasingly hard time paying their pastors’ medical bills, causing us to ask whether chronic disease rates among pastors are on the rise. We now know that’s the case. And that means that over time, it’s likely that pastors will no longer have the longevity advantage.”

Obesity is often a precursor to other chronic conditions such as hypertension, heart disease, diabetes and arthritis. As a May 2010 article in The Atlantic points out: “Obese Americans spend about 42 percent more than healthy-weight people on medical care each year. Improper weight and diet strongly correlate with chronic diseases, which account for three-fourths of all health-care spending.”

Proeschold-Bell said that when she shares the study findings with clergy, she sees them nodding their heads.

“They’re not surprised. But they are concerned,” she said.

“It’s a wake-up call,” said one pastor participating in the study. Another expressed alarm at how sick clergy are as a group: “I’ve always known it, but now there is concrete evidence supporting it.”

A fair comparison

The Clergy Health Initiative study is unique in that it compares the health of a group of clergy to a comparable group in the overall population. One other study, conducted in 2002 by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, found that 34 percent of ELCA pastors in the United States were obese, compared to a national average of 22 percent. But that study did not take into account the fact that nearly three-quarters of the ELCA pastor respondents were male, with an average age of 50.

The Clergy Health Initiative survey set out to learn whether clergy were unhealthier than people with similar demographic characteristics. The survey, conducted in 2008, had a 95 percent response rate among United Methodist clergy statewide, ensuring that the data was representative of the state’s 1,820 clergy.

Researchers posed to the pastor group the same questions that had been asked to approximately 30,000 North Carolina residents participating in the 2007 and 2008 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS), a telephone survey sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and conducted annually by each state. The questions gauged whether individuals had ever been diagnosed with a variety of chronic diseases. Researchers used participants’ self-reported weight and height measurements to calculate BMI.

To match the profile of the majority of the clergy in the state, the study incorporated data only from clergy and people who responded to the BRFSS survey who were white, between the ages of 35 and 64, employed, and covered by health insurance.

Beyond Methodism

Are other clergy at risk? While the Clergy Health Initiative study is limited to a single state’s United Methodist clergy, it’s possible that clergy in other denominations are experiencing similar health concerns.

Jack Carroll, Williams professor emeritus of religion and society at Duke Divinity, who directed Pulpit & Pew, a major research project on ordained ministry in the United States, said that his cross-denominational research didn’t uncover significant differences between clergy in the South and in other regions.

“I don’t think Methodists are all that different from the others,” he said. “I would think it would be a fairly interesting finding and one that could be generalized from North Carolina (and North Carolina Methodism, really) to other traditions.”

Stephen McCutchan, a retired minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA) and member of the Presbytery Pastoral Care Network, has witnessed similar tendencies among clergy.

“In my experience, a big resister to care for clergy is the clergy. They feel that it’s one more thing that they have to do, and they don’t do it well.”

But by not attending to their physical, mental and spiritual health, clergy are missing an opportunity to care for their congregations, McCutchan said.

“When they run themselves ragged, they are emulating many members of their congregation. Everyone is time-stressed in this world,” he said. “And how you learn to manage that and also accomplish your purposes is an important balancing act. I think that clergy don’t see that as part of their testimony -- they see it as extra. They see it as, ‘After I get my work done, I’ll have time to do this,’ as opposed to, ‘This is part of the importance of my witness.’”

Health ecology

The Clergy Health Initiative study will be conducted again in August 2010 and in 2012, enabling researchers to pinpoint more accurately the causes of the health disparities. Yet it’s not hard to identify some likely reasons for obesity and poor health among the clergy, Proeschold-Bell said.

The Clergy Health Initiative has found that clergy tend to put the needs of others before their own in their work to serve God. Other studies indicate that pastors’ working conditions also may play a role: they are employed in a vocation that is sedentary, and they spend an average of four evenings a week away from home. They frequently work more than 50 hours a week, with a schedule that varies wildly.

In North Carolina, as in many other states, clergy are surrounded by others with serious weight concerns -- North Carolina ranks 12th-worst in the nation for obesity. People who eat on the run or who live in more rural areas tend to have fewer healthy food choices as well.

Emerging research linking obesity risk to high stress also signals that the very nature of pastors’ responsibilities may put them at higher risk. Key sources of stress -- mobility, low pay, inadequate social support, high time demands and intrusions on family boundaries -- have been found to decrease healthy behavior.

The Clergy Health Initiative study opens the door for further work on how to create healthier environments for clergy. Based on the study findings, the Clergy Health Initiative has been piloting a program aimed at addressing these health concerns through periodic medical checkups, health coaching and funds clergy can use to improve their health.

“It’s hard for pastors to effect change on their own, because they’re part of a larger ecology that puts significant demands on their time. And those demands, if not held in check, take a toll on the body and the spirit. Research like ours helps make a case for why certain systemic pressures need to shift,” Swift said. “Our goal is to help pastors break out of that cycle.”