Epilogue

The road wound up and up the mountain, through laurel and rhododendron groves, past a great iron gate, finally spilling onto a graveled ridge with a spectacular view of the southern Appalachians. A German shepherd, snoozing on the driveway, lifted a wary eye. I felt unexpected anxiety. It was difficult to spend three summers and a sabbatical researching a man’s life and then meet him in person. For a moment, before getting out of the car, I thought this was a bad idea -- a really bad idea. I should go back to the quiet safety of my office in the university library. My wife, Katherine, safely buckled into the passenger seat beside me, felt the same way. Several months earlier she had given up idyllic days of retirement to pore through musty boxes of letters to the preacher. Our aim now was not to interview Mr. Graham in any formal way. He was nearly ninety, and the days of formal interviews were long past. Rather, we hoped only to meet the legend whose life and personality fill the pages of this book.

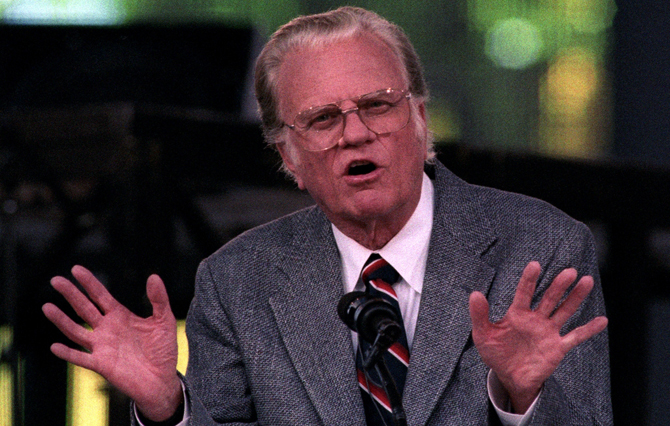

The countless photographs we had seen of the spacious log home atop a mountain near the historic Presbyterian village of Montreat, North Carolina, came to life. Entering through the back door, as all visitors do, we were escorted by two nurses into a country kitchen, graced with a great stone fireplace and antique ironware, then down a long hallway festooned with family photos and mementos of world travel, and finally into a surprisingly small and cozy study. Mr. Graham was sitting in an easy chair. The flowing white hair and sky blue eyes immediately captured our attention. He stood with difficulty, first to shake Katherine’s hand -- a Southern gentleman to the end -- and then mine. We expressed condolences about Ruth Bell Graham, his wife of sixty-three years, who had died several weeks earlier. Katherine, always better at those things than I was, chatted with him about his health and our beloved state of North Carolina. Mr. Graham said our town of Chapel Hill was one of his favorites. Though the once-commanding baritone had softened to a little more than a whisper, the Carolina drawl was still unmistakably that of Billy Graham.

After a few minutes, Mr. Graham’s special assistant, standing nearby, said, “Billy, Grant is writing a book about you.” Obviously puzzled, Mr. Graham responded, “Why? Why would you want to do that?” Taken aback, I finally mumbled, “Well, you have done some important things.” Without hesitation, he said, “No. The Lord has done some important things through me.” It was hard to know where to go from there. Though I had determined not to get into substantive matters, I could not help myself. I asked about Chattanooga. I said there is some disagreement among historians about whether you pulled down the ropes in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1952, or in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in 1953. Again without hesitation, he said, firmly, “Chattanooga. I remember it well. I walked out in the auditorium and pulled the ropes down. Some people did not like that.”

Now rolling, I asked Mr. Graham if he remembered his trip to the peace conference in Moscow in 1982. The question triggered memories of his friendship with Mikhail Gorbachev, and then of his private talk with Winston Churchill back in the summer of 1954. Abruptly he directed the conversation back to Katherine, followed by a good deal of unexpected bantering. “What do you do, Katherine?” When she said she was a retired middle school guidance counselor, he asked how she liked retirement. He asked about our children and grandchildren and talked about his children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren, allowing that he had “about thirty” great-grandchildren.

Throughout the visit, Mr. Graham’s wit sparkled. He wondered how we managed to live in Chapel Hill -- the home of the University of North Carolina -- with me teaching at Duke. With a wink he demanded, what happens in basketball season? He mentioned his Parkinson’s disease. “You know what happens when you get Parkinson’s? Your handwriting gets illegible and your sermons longer.” The conversation drifted to a book his nephew Kevin Ford was writing about how to avoid church conflict. “Kevin has a lot to write about,” he grinned. Striking up a conversation with a watchful young nurse in the corner, I asked about her nursing background. She said she had gone to Duke School of Nursing. When I asked why not Carolina, Mr. Graham intervened: “Because Duke is easier to pronounce.” And so it went.

A second visit followed in 2009. (A third one followed in 2011 and a fourth and final one a few weeks before his ninety-fifth birthday.) We found Mr. Graham frailer. He remembered us and invited us to have a seat. He noted that his vision had deteriorated, he could no longer read, and clearly he did not hear very well, either. But the flowing white hair and unmistakable rolling baritone remained the same. “What brings you to Montreat?” At first I thought he was spoofing, but I quickly realized that the question was genuine. It reflected the utter unpretentiousness so many other visitors had experienced and written about. He asked how the book was coming along. He demanded, with mock sternness, “How many chapters do you have?”

We told Mr. Graham that in the course of researching a work on his place in American history, we had discovered a cache of answered but long-forgotten letters that young children had posted to him in the early 1970s. We said that the letters brimmed with unintentional humor, comments about money, requests for stickers, observations on pets, theological questions about things great and small, and, above all, expressions of love and gratitude. We mentioned how most adults addressed him as Dr. Graham but children often called him Billy. He liked that. He wished everyone would call him Billy. “I don’t have a doctorate, you know.” He laughed heartily when we told him of the child who wrote that his Cocker Spaniel had become a Christian. And when we told him about another child who sent a dime, then added, “That’s all I have. Get used to it,” Mr. Graham said the children’s letters touched his heart.

The time passed quickly as we rummaged over many topics. He chatted about good friends, now gone -- Hank [Henry] Luce, David Frost, and Walter Cronkite, among others. We praised the handsomeness of the dog outside, and told him about our bulldog, and that opened a floodgate. A good deal of the conversation revolved around dogs, including his beloved Rottweiler mix, China, who did not get along all that well with the German shepherd. A sampler hung on the wall next to his chair. It said only, “Gal. 6:14.” [“But God forbid that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world is crucified unto me, and I unto the world.”] When I asked about the sampler and the Scripture passage, he said he wanted to preach one more time, on that passage. “It was [Charles] Spurgeon’s favorite,” he added, evidently for the benefit of a church historian.

An hour slipped by, he was tiring, and we stood to leave. Mr. Graham asked us not to go so soon. “You just got here.” Remembering that I did, after all, teach in a divinity school, I offered to pray with him. He said, “I would like that very much,” and extended his hand. Taking that glass-frail hand, which had gestured before more than two hundred million people in person, and hundreds of millions more on television, did not inspire much eloquence in me. But it did inspire an indelible memory. Leaving, Mr. Graham made us promise to “drop by” any time we were “in the neighborhood.” The long drive back down the mountain was a quiet one. I knew it would take a while to process.

By the end of the four-hour drive home, five impressions stood out with clarity. The first pertained to something physical: the voice. Though Graham actually spoke very softly, his voice resonated. Historians have rightly invested considerable effort analyzing Graham’s theology as well as his preaching style. Yet close up, it seemed evident that a lot of Graham’s appeal rested in something as simple yet mysterious as the human voice. The second impression pertained to the wit -- much of it self-deprecating -- and his delight in bantering. In Mr. Graham’s public performances, canned jokes at the outset of the sermons abounded, and the audiences clearly loved them. But wit was another matter. It did not come through very well on radio or television, and certainly not in the prose. But in person it bespoke a lightness of touch. In ineluctable ways it facilitated the expression of the charisma. The third impression centered on Mr. Graham’s down-home, “awww shucks” style of self-presentation. I knew he had an uptown side too, but conversing one-on-one left little doubt that the default mode ran closer to the dairy farm than to the White House.

A fourth impression was the humility that virtually all visitors observed year after year. At times in Graham’s long career, especially in his comfortable Establishment days, the humility got tied up with self-promotion. Exactly how they wound together defied easy untangling. Yet being with the man in person confirmed that humility -- deep, authentic, the real thing -- constituted the core of his identity. We were not the first to experience it.

And finally there was the preacher’s faith. It commandeered my memory bank. It presented itself as at once the least and the most palpable of things, elusive yet everywhere. He did not wear it on his sleeve, as if he wanted to make sure we saw it. Rather, it seemed simply to bubble up. When he spoke quietly of how the Lord had chosen to use him, and he had no idea why, we knew it was not an act. He really believed it.

Excerpted from “America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation” by Grant Wacker, published by the Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Copyright © by Grant Wacker. Used by permission. All rights reserved.