When Joel Carpenter planned a trip to Africa in 1990, he asked around beforehand for names of people he should meet.

A colleague told him he had to meet Kwame Bediako, an up-and-coming Ghanaian theologian “who has a vision for Christianity in Africa like no one I’ve ever seen.”

When Carpenter, who was then religion program director of the Pew Charitable Trusts, arrived in Accra, Bediako and his wife, Gillian Mary, picked him up at the airport and drove him straight to their home.

Carpenter stayed with them, met their two sons and toured the Akrofi-Christaller Institute of Theology, Mission and Culture, which Bediako had founded.

Carpenter discovered that Bediako was indeed brilliant. The man had earned two Ph.D.’s -- one in France and one in Scotland, working with Andrew Walls.

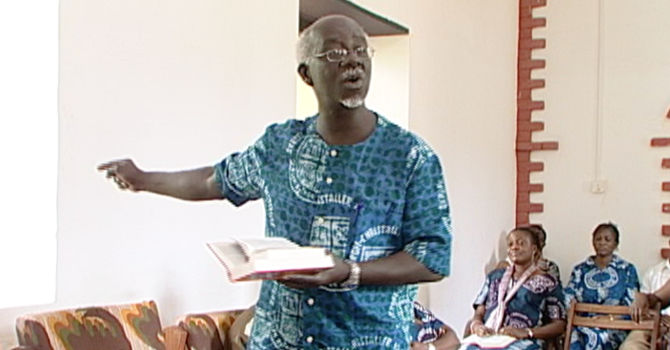

He was also pious, warm, hospitable and gracious, a spellbinding speaker and a passionate advocate for African Christianity and African theology.

So began a friendship that lasted until Bediako’s death in 2008.

“The man just oozed charm,” said Carpenter, who’s now a research fellow at the Nagel Institute for the Study of World Christianity at Calvin University, where he was the founding director. “Listening to him was like listening to a symphony. He was an exciting person to be with.”

Carpenter, a historian by training who served as provost at Calvin for 10 years, is writing a biography of his old friend and hopes to raise Bediako’s profile in the West.

Carpenter, a historian by training who served as provost at Calvin for 10 years, is writing a biography of his old friend and hopes to raise Bediako’s profile in the West.

Bediako grew up in the heady early days of the emerging Ghana republic, which gained independence as the first postcolonial sub-Saharan nation in 1957. He was a French major at the University of Ghana in the mid-’60s, when the school was aspiring to become the Oxford of West Africa.

He was fascinated with French existentialist philosophy and became an atheist for a time. But while pursuing postgraduate studies at the University of Bordeaux, he underwent a dramatic conversion. He immersed himself in ministry at a local evangelical church, and there he met the English woman who would become his wife. (She also is an accomplished scholar and partner in the work who serves as deputy rector of the Akrofi-Christaller Institute of Theology, Mission and Culture.)

“His life story is so fascinating. There have been several dissertations and dozens of articles written about Bediako’s theology, but I want to put it in context of his life,” Carpenter said.

Carpenter spoke to Faith & Leadership’s Sally Hicks about Bediako’s theology and his deep conviction that African theology is equal to -- and has important things to say to -- Western theology. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Andrew Walls has written that “Kwame Bediako was the outstanding African theologian of his generation.” For readers who might not be familiar with Bediako’s work, why is he so significant?

Joel Carpenter: He was in the second generation of African Protestant theologians who were post-independence African theologians. Kwame’s most fruitful career was from the late ’80s up until his death in 2008.

He was only 62 years old, unfortunately, at the time he passed, so he was very much a theologian of the ’80s, ’90s and aughts. He really benefited from a prior generation of African theological leaders, people like John Mbiti, the Kenyan who wrote seminal works on the relationship of Christianity to the primal religions of traditional Africa.

Desmond Tutu is more famous, principally for his prophetic and pastoral role in South Africa. But Bediako -- for tropical Africa and for the African nations that were already independent and struggling with a postcolonial existence -- he was really seminal.

F&L: Let me ask you a question in two parts. What is important about his work for African Christians? And why is it important for American Christians and theologians in particular to know his work?

JC: Bediako said the question that bothers us the most -- whether we’ve reflected on it or not -- is, What does it mean to be Christian and African? One of the most abiding criticisms of postcolonial African intellectuals is that Christianity is alien to Africa; it’s not an African religion.

Bediako said that Christianity has made its home in Africa. Africa has in fact become the new heartland of Christianity in the world.

His best-known book is “Christianity in Africa: The Renewal of a Non-Western Religion.” He says not only has Africa become Christian territory in many respects, especially sub-Saharan Africa, but there are nations in sub-Saharan that have a much higher percentage of the population that claim to be Christian than in the U.S.

It’s a religion that’s made its home in Africa, but there is still a lot of alienated practice and divided hearts and minds. This is something that Mbiti and others before said, too -- that there are many Africans who profess Christianity but live a divided existence.

Christianity as presented to them is a way to be saved from torment in the life to come, a way to go to heaven. But it was not presented to them in compelling and African ways as the faith to live by here and now, or the faith “that charms our fears, that bids our sorrows cease,” as Charles Wesley put it.

How is Christianity that for Africans? That’s what Bediako was working on.

F&L: So his argument was that it’s not just something imported by colonizers?

JC: It’s not just an imported religion anymore. In what ways is it actually becoming African, and then what can this distinctively African kind of Christianity say to the rest of the world?

Bediako was always looking over to the West as well, and speaking to the West. He did his two doctorates in France and Scotland, and so he was very much engaged in Western thought, Western intellectual questions.

His first theological degree at London Bible College was very much in a Western theological tradition. He understood the abiding questions of Western theologians, the kind of apologetic work they were trying to do over against the “cultured despisers of religion” in post-Christian Europe.

He said, “Those aren’t our questions; our questions run in different ways. I think you can understand your own Christianity better, your own Christian roots better, if you hear about Christianity in our context.”

He was continually traveling to the West, very much in demand to speak. He gave the Stone Lectures at Princeton, gave the Duff Lectures at Edinburgh, the Henry Martyn Lectures at Cambridge.

So he was known among Western theologians, but I’d say he was still trying to break into their syllabi of required reading.

F&L: And you argue that he should be included, right?

JC: That’s right. [The Western attitude is that] theology is the way Westerners do it -- essential and normative. Right? These other theologies have some kind of modifier in front of them, so it’s African theology or it’s Latin American theology. He’d say, “No. We need to transform this whole enterprise.”

So what does he have to offer to the West?

He said, “Well, Christianity is thriving where we are, and it’s waning where you are, so maybe there is something that could be helpful to you all.” I think there are at least a half-dozen things that he would point to.

One, he would say that Africans live into the faith.

Reading the Scriptures is participatory. He said Africans read into the text; they read themselves into it. These stories are fresh to them. This is not something from long ago and far away that somehow we’re trying to interpret the spirit of. They feel like they get it and they are right there in it.

He said the same about worship. If you go to a typical Ghanaian worship service, whether it’s Roman Catholic or Episcopalian or Presbyterian, you’re going to see dancing. You’re going to see people moving around. You don’t sit there and get the plate passed to you; you head out into the aisle. The musicians save their best music for the offertory, and you dance and you wave a hankie, because the Lord loveth a cheerful giver. Right?

Christianity is not a spectator sport. You live into worship. You enter into the biblical story. I think the closest thing we see in the West to that is Pentecostalism.

He’d say the real core of African spirituality is prayer and that African Christians very frequently see an immense trust in God and dependence on God. So “give us this day our daily bread” is not just a figurative matter.

If there’s a doctor and a nurse in a clinic nearby but they’re constantly out of medicine, or if the local healer herbalist wants to charge you too much for his ministrations or her ministrations, what are you going to do? You pray to the Lord.

So say a Danish missionary comes to Nigeria in the 19th century and says, “Believe in Christ to be saved; Jesus is the Savior of the world.”

[The African response would be,] “Well, how about these folk who I know are hurting from witchcraft?” And the missionaries would say, “Oh, that’s superstition. Don’t believe it.”

These folks say, “Look, we’re not stupid. We have seen people get mysteriously ill. We know what happens. So does our faith help us with that or not?”

The longer we get away from the days of independence and the departure of the missionaries, [with] the rise of these new churches, the more Africans are saying, “These are the things that matter to us, and this is what we expect Christianity to address.”

One of the things Bediako said again and again -- and I think he learned this initially from Walls and from others at Aberdeen -- was that historically, Christianity has taken root mostly in places where the prior religion was a primal religion, a tribal spirituality, and not one of the great, high religions.

F&L: Explain that a little more.

JC: Well, it’s a kind of spirituality that you see in Indigenous people around the world, whether we’re talking Native Americans or Samoans or West Africans or native Taiwanese or tribal folks of northeast India. That was our ancestors in Europe as well.

We’ve been living in a civilization where Christianity has been dominant -- in fact, a monopoly religion -- for centuries. But at one point, Europeans were asking similar questions as Africans about, “Why does this faith that you’re talking about matter to me?”

There are lots of different variations to [Indigenous religions], but a lot of similarities as well, such as belief in a great creator God, belief in a spiritually animated world, and that people need to make their way through this myriad of spiritual forces.

So through the years, Christianity has made its greatest inroads with people like that, and it’s had its greatest resistance in places that had other quite subtle and carefully articulated and temple-situated faiths -- Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism.

It’s ironic, because in 19th-century missiology, the Western missionaries expected to have their dialogues and to make their most progress with some of these religions that have theology and ethics carefully worked out and archived and encoded into text. But God seemed to have other plans.

Bediako would say our Christianity has this spiritual undercarriage that comes from primal religions. It’s still part of our substructure of Christianity.

[Let’s say you're a missionary and] you’ve come to West Africa and you’re sharing the gospel with Yoruba people in southern Nigeria.

One of the first things the missionaries want to do -- and it typically takes them about a generation to get it done -- is to translate the Bible into Yoruba. So when the Bible talks about sacrifice or the Bible talks about prayer or the Bible mentions God or talks about the Spirit or spirits, it’s using the very words that were the terminology of the old Yoruba religion.

Those words get invested with new meaning, but it’s the linguistic system, the cultural memory, that’s being carried over into Christianity and provides a spiritual undercarriage for Christianity.

So Bediako would say, “Do you know that about your own heritage, you Westerners? In what ways has that happened for you? How might it help you today to be more cognizant of that?”

Bediako says go back and look at the initial dialogue someone like St. Patrick would have had as he went over to minister to the Irish or St. Boniface in the Low Countries.

F&L: You also make the point that the North American and European society is growing more religiously diverse, which is something that African theologians are used to. In what way does that change the theology?

JC: In Western theology, its handmaiden or its conversation partner is philosophy. Bediako would say that it should be religion. You should learn about comparative religions. You should learn about interreligious dialogue. You should learn about how your neighbors’ faiths address these kinds of compelling life questions that you want your faith to address, too.

So he would say that religious studies, religious phenomenology, comparative religions, history of religions, those ought to be the intellectual handmaidens or conversation partners of theology, more than philosophy.

I think there’s really a rich trove there for Western theologians, especially at a time of growing dissatisfaction with what a post-Enlightenment worldview has done or not done for us.

Bediako says, and Mbiti said, “We have dined with you theologically; won’t you come and eat with us?”