Failure is never easy -- even for God.

In the middle of the wilderness, God made a decision, and it didn’t go well at first. God made the call to summon Moses to the top of Mount Sinai and give him the law inscribed on two stone tablets.

In Moses’ absence, the people grew anxious and demanded of Aaron, “Come, make gods for us.” To mollify them, Aaron took their jewelry and fashioned a golden calf. “Here are your gods, O Israel,” he said. To celebrate, the people ate, drank and were very merry indeed. God was angry and wanted to destroy the people, but Moses talked God down off the ledge. Yet when Moses descended and saw for himself what was going on, he threw the tablets down and destroyed them.

There’s no other way to say it: the first attempt to give Israel the law was an epic fail. But was it a bad decision? Was the decision to give Israel the law in the first place a poor one?

Failure is a hot topic in church leadership today, with seminaries and denominations and congregations exploring the relationship between failure and creativity, innovation and institutional problem solving.

With all of this talk, however, we’re still missing one crucial element in our conversations around failure: decision-making. We rightly talk about the importance of creating cultures of trust and experimentation. We point out the importance of distinguishing between good experimental failures and bad ethical ones.

But more fundamental is decision-making itself. How do we distinguish between good decisions that happen to result in failure and bad decisions that lead to failure? Or how do we tell the difference between a bad decision that just happens to turn out well and a good decision that succeeds according to plan?

Let’s say my high schooler attends a wild party, drinks and then makes the decision to drive home.

This is an absolutely terrible decision.

If he makes it home without incident, this is a good outcome, but we would never say he should repeat the initial decision to drink and drive. On the flip side, if my kid drinks at this party but then calls me to come pick him up, we would commend him for at least having the sense to call for help. If we have an accident on the way home, this is a poor outcome. But the bad outcome doesn’t mean the decision to call me was wrong. It was a good decision that just had a bad outcome.

Church leaders rarely make this distinction, and it’s a problem.

I started out in ministry leading a new church development. I had no idea what I was doing, which is probably the only reason I agreed to try. You learn to fail in new church development. A lot. But we have no idea in advance which plants will fail and which will thrive.

Every group starting out thinks it has a chance, or no one would invest the time, energy and resources. Yet every time a new plant fails, people come out of the woodwork to say that they were afraid this would happen and that it was a mistake all along. If the outcome is bad, it must have been the wrong decision in the first place.

We have to stop reasoning like this. Good decisions can and will lead to bad outcomes.

Instead of reasoning from the outcome, we have to spend more time thinking about the quality of the decisions we make.

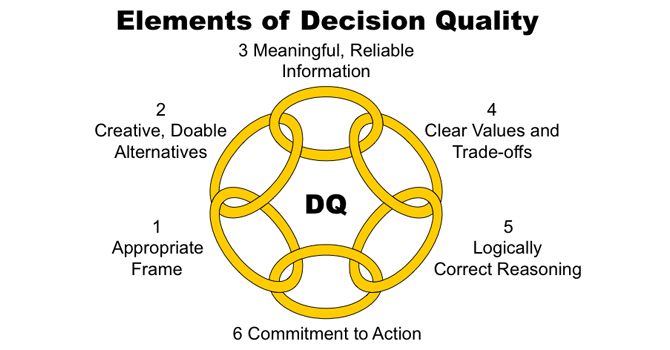

Leaders at Stanford’s Strategic Decision and Risk Management program offer a “decision quality chain” for distinguishing between decision quality and outcome. It contains six elements: appropriate frame; creative, doable alternatives; good information; clear values; sound reasoning; and commitment to action.

In the first step of this process, leaders consider the frame, or context, of a decision to ensure that they are solving the right problem. The right solution to the wrong problem will only lead to frustration, and it happens all the time.

Second, leaders articulate creative and doable alternatives. Especially when we feel convinced we’re on the right path, it’s easy to avoid thinking through alternatives at all. This is a mistake. Without identifying and evaluating several doable alternatives, including doing nothing, we haven’t really made a decision.

The third step is assessing the value of our information: is it based on the intuition of the loudest person in the room, or is it rooted in something more solid? Good information is particularly challenging to come by in the church.

Because of this, this fourth step is all the more important for us. Leaders carefully consider whether the proposed solutions are grounded in the core values of the body we serve. The principle of traditioned innovation holds that new ideas must be rooted in who God has always called us to be, not just the latest and greatest trend.

Next, leaders use sound reasoning to consider whether they have blinds spots that are coloring their judgment. Do we think we are seeing clearly when we really aren’t?

Finally, leaders assess whether the organization is committed to the proposed action. This last step brilliantly pushes leaders to think through all the parties who will ultimately need to embrace the changes ahead. If there isn’t commitment to action, even the best decisions will be dead on arrival.

This process is invaluable -- but it includes only a single step inviting leaders to consider what biases may be influencing our thinking. We might infer that heuristics and bias can be dealt with by simply being aware of them.

Yet over and over behaviorists have shown that cognitive bias is far more deeply rooted than we’ve realized. With each step of the process, then, I suggest that a particular bias be considered, to remind leaders to be attentive throughout the decision-making process.

For instance, during the first step, setting the appropriate frame, leaders must guard against “narrow framing,” the temptation to transform complicated decisions with many facets into overly simplistic questions. It’s important to slow groups down to make sure they’ve considered every angle. When dealing with a challenge, I lead groups to pose solutions only after they have restated the challenge and asked for clarification. This can be frustrating to the people who want to move immediately to problem solving, but short-circuiting the process often leads to good solutions to the wrong problem.

When it comes to creative, doable alternatives, leaders should be mindful of the anchoring effect. Anchoring causes us to get stuck on early ideas, making it difficult to think creatively. Design firms like IDEO avoid using the staple of so many church boards -- the traditional brainstorming session -- because of this. It can be more effective to break into small groups to work on multiple ideas at the same time. If a team has only one or two good options at the end of the day, members should demand more possibilities.

During the third step -- getting good information -- the greatest threat is confirmation bias. Even experienced pastors have seen only a small number of congregations, and all of us are prone to remember experiences that confirm our beliefs. The danger is that groups will make decisions based on little more than hunches and anecdotal experiences from a tiny set of data.

At the next step, affect bias can lead groups away from the deep values that root them. Anxiety or fatigue -- common among decision-makers -- can affect our perception in powerful ways. To counter this, leaders must regularly articulate the organization’s deepest values to keep the group on track. This is one area where the church should really shine in comparison with other institutions. Prayer and theological reflection are not only our birthright; they are the very practices that help us slow down and remember that God is God and our fears are not.

Next, when it comes to reasoning, one of the most common biases -- the optimism bias -- leads us to overestimate our abilities. Simple awareness of this bias does not make it go away; leaders must keep in mind that it will inevitably affect and hinder our thinking.

In the final step, commitment to action, leaders must be mindful of the power of loss aversion. Behaviorists have shown that people are twice as unhappy about losing an object or practice as they are about gaining something else. Change, in other words, is painful. Even good change means loss in some way. It’s easy for leaders to become so focused on our brilliant and exciting solutions that we forget about the living, breathing humans who need to be convinced of them.

Remember how God’s first attempt to give people the law resulted in miserable failure? I asked whether it was a bad decision. What do you think?

I say the answer is absolutely not. While the first outcome was terrible, the decision to give the law was still a good one.

When leaders face good decisions that result in poor outcomes, they have to persevere and try again, and that is exactly what God and Moses did.

Two chapters after Moses destroyed the first tablets, we find God telling Moses to cut two more, just like the others. God again inscribed the tablets with the law. God didn’t modify the plan. God didn’t say he had made a mistake.

No, the first decision really was a good one. It just had a bad outcome. And so God and Moses tried the same idea again, and the second attempt resulted in the same commandments that continue to guide us today. Thank goodness God and Moses didn’t confuse a bad outcome with a bad decision.