Christmas is a time when we hear much about kings. The King of all was born and laid in a manger. King David was his ancestor. King Herod tried to kill the newly born King. Three other kings came to worship the true King. And so on. What we don’t often hear much about, however, is the dramatic innovation that took place when Jesus was first called “king.”

Questions to consider

Questions to consider:

- How does military might figure into what you think a good political leader ought to be able to do?

- Why would God send a king whose earthly life ended in what looks like defeat?

- How might we rethink our notions of power if we took seriously the crucified shape of King Jesus' power?

Israel did not always have a king. In fact, one of the more striking themes in the Old Testament is God’s reluctance to allow Israel a monarch. If we follow the overall story told in the Old Testament, we are carried along in a narrative movement from an apparent anti-monarchial stance to the eschatological exaltation of the Davidic line. Through Joshua, Judges and the opening of 1 Samuel, the Old Testament narrates on and off the reluctance of God to give Israel a king together with Israel’s corresponding insistence that she have one. But after First and Second Samuel’s stories of the anointing/election of Saul and David, the Old Testament moves quickly to a distinctly shaped and theologically developed notion of kingship, namely, that the king should reflect the virtues of King David (read again First and Second Kings).

Despite his obvious blunders, “David” becomes a kind of a symbol or cipher for what true kingship under God should be. By the time of the New Testament, messianic expectation included as a matter of course the conviction that the Messiah would be the son of David and would establish his kingly rule over the house of Israel (this can also be seen in certain places in the Old Testament, such as in the Psalms). In Jewish understanding, to be Messiah was to be the King of Israel. Thus it is of utmost importance to the New Testament Gospel writers not only to trace Jesus’ paternal lineage through Joseph to King David but also repeatedly to portray Jesus’ messianic role as essentially bound to his identity as the son of David.

Given the importance of the royal shape of messianic expectation for readers of the Old Testament -- and perhaps first century Jews especially -- it would be difficult to think of a greater innovation on this theme than to say that the messianic king is not the one who has come to liberate Israel and drive the Gentiles out of Palestine but instead is he who was killed at the hands of the Romans. Indeed, it is no wonder that the disciples’ joyous exclamation, “Blessed is the King, the one who comes in the name of the Lord,” (Luke 19:38) turns to dejection and political disappointment after Jesus’ execution: “We had hoped he was the one who would redeem Israel,” say the devastated disciples on the road to Emmaus. (Luke 24:21) Jesus simply did not turn out to be a military monarch, a conqueror who could stun and defeat his enemies by his power. He was instead a suffering, crucified and dead messiah -- by all appearances, a defeated king. The innovation on the theme of Davidic kingship is radical almost to the point of breaking with tradition altogether.

And yet, the very newness -- even shock -- of the innovation depends for its fullest meaning on a proper grasp of the tradition that constitutes the background of its radical nature. Perceiving this essential connection between the meaning of the New Testament’s innovation and the tradition on which it depends prompts a careful rereading of the tradition to inquire whether it might exhibit a deeper point of contact with the innovation.

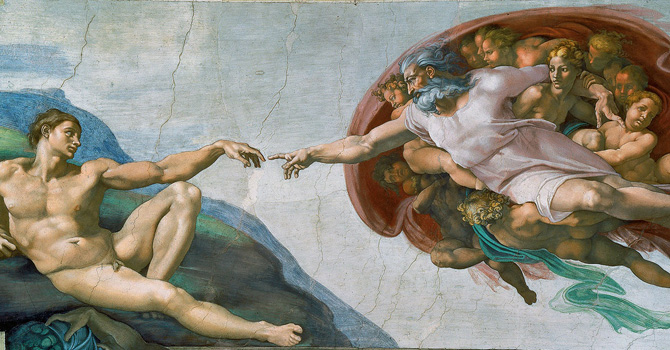

And in fact it does: God’s reluctance to deal in kingship bespeaks his knowledge of the reality of monarchial violence and the way military victory might shape Israel’s hopes for the future. In order to break this connection between violence and hope, the notion of kingship must be raised to its most fervent level -- that of hope in military messianic deliverance -- before it is shattered by the life and death of the true King. In this case, it is the radical innovation that actually creates the vision with which to see the deeper layers of God’s salvific purpose in the tradition (think here, of course, of the so-called “suffering servant” of Isaiah 53).

To be God’s true monarch, as the three kings were to see so vividly in the infant Jesus, is not to assume the mantle of might but is instead to become vulnerable, to live gently even unto death and to trust in the hope of resurrection.