John F. Kennedy had a wicked problem on his hands. The situation in Vietnam was growing more and more complicated, and he knew its solution would require a dramatic effort from his office.

And so he did what anyone in such a powerful position would think to do: he assembled a dream team of problem solvers. By scouring the ranks of America’s elite institutions, Kennedy found the nation’s smartest guys.

Or so he thought.

As David Halberstam argues in “The Best and the Brightest,” Kennedy’s national security team actually suffered from a curious lack of intelligence. His advisers came up with intellectual answers to practical problems, resulting in “brilliant policies that defied common sense.” Accordingly, Kennedy’s team exacerbated the very problems it had been tasked with solving.

Kennedy’s mistake did not lie in his desire to assemble the smartest people America could offer but in his definition of “the smartest,” which turned out to be rather narrow and restricted. His team ended up looking particularly homogenous in background -- Ivy League-trained intellectuals and business leaders, for the most part. They were all undoubtedly “smart” but also all the same kind of “smart” -- which, collectively, resulted in decisions that weren’t smart at all.

A decade after the Vietnam War ended, psychologist Howard Gardner challenged the logic that birthed Kennedy’s team. There is no general “intelligence,” he argued, but only multiple intelligences, which are largely distinct from each other. In Gardner’s reckoning, Kennedy had assembled the most intelligent “logical-mathematical” people in America. But in doing so, he had ignored the various other cognitive capacities that are so essential to solving wicked problems like Vietnam.

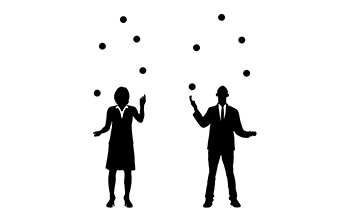

In order to solve a wicked problem, you must be able to attack it from various angles and develop multiple strategies. In order to do this well, you need a diverse group of thinkers whose particular casts of mind complement -- rather than reinforce -- each other.

An intellectual adept in abstract reasoning, for example, may struggle to keep his thoughts grounded in practice, and might lack the wisdom born of practice. That intellectual needs to spend time with a gifted practitioner whose mind has been trained to test projects for feasibility.

Or consider an artist, whose capacity for creative thinking leads to unforeseen avenues of exploration, the kind of “outside the box” thinking that organizations often covet. But creativity cuts both ways; artists are also notorious for proposing absurd ideas that make sense to no one but themselves. On a problem-solving team, then, the creative insights of an artist will be complemented by the careful, analytical knowledge of a lawyer or an engineer.

No single cast of mind can solve our most wicked problems; we need diverse minds, addressing a problem from every possible angle.

Groups ideally will have multiple forms of diversity and, when possible, overlapping perspectives. One artist in a room full of scientists might question whether she has anything to contribute, but two or three artists are more likely to build off each other’s perspectives and insights.

It takes time for people from such diverse backgrounds to learn to work together. It is sometimes easier for people who speak Spanish and French to communicate with each other, through translators, than it is for a scientist, a musician and a social psychologist to converse.

There are few capable translators for the different conceptual languages people learn to speak in their vocations. But we need those diverse perspectives, and so we also need the patience to learn how to communicate via a “lingua franca.”

Within such a cognitively diverse team of individuals, individual cognitive diversity also becomes crucial. Those who possess a range of intelligences can hold various aspects of a wicked problem in constructive tension and seek generative solutions at their intersections.

Take, for example, the wicked problem of education. Tracing the causes of educational problems quickly leads one into unexpected territory, like health care disparities or early-childhood parental practices. Moreover, many of these factors are often set against each other: Are educational problems more about family upbringing or school culture? Should we promote the sciences or the arts? Is the responsibility for building students’ character left to teachers or to parents? It takes a flexible mind capable of thinking in diverse ways, then, to find solutions to our educational problems.

One praiseworthy example comes from education writer Paul Tough in his new book, “How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity and the Hidden Power of Character.”

Tough refuses to engage in the “either/or” oppositions so characteristic of the education conversation. Instead, he broadens the conversation. He explores the connections between in-school performance and the security of attachments at home, between cognitive ability and character traits, between students’ ability to focus and their nutritional habits.

In order to arrive at his wide-reaching insights, he had to inhabit the diverse cognitive worlds of sociology, psychology, morality and medicine. Only by inhabiting such diverse worlds did Tough discover the intersecting perspectives and experiments that could lead to creative and lasting solutions for one of our most wicked and challenging problems.

Yet however much Paul Tough may have contributed on his own, he is quick to point out his reliance on others for the cognitive diversity he needed.

Geoffrey Canada, the pioneering administrator Tough profiled in “Whatever It Takes,” helped him see the educational implications of a child’s early upbringing. And it was an economist, James Heckman, who paved the way for Tough’s work on learning and moral character. In reading “How Children Succeed,” one gets the sense that Tough’s solutions to educational problems emerge from nourishing relationships among people who, individually, think and live in very different ways than he does.

Cognitive diversity is distinct from, and a complement to, other forms of diversity in groups, especially when attacking wicked problems. People of diverse racial, ethnic, gender and socioeconomic backgrounds often represent different cognitive perspectives as well, and it is important to listen carefully for the different habits of thinking, living, feeling and perceiving that such diversity contains. In our culture, though, we have tended to equate diversity with a person’s “identity” markers.

When forming groups and teams to work on wicked problems, it is critically important to ensure that we have the relevant forms of cognitive diversity represented early in our processes. Such diversity might be provided by the stakeholders we engage in the framing of our questions and the development of our experiments.

We might also need to broaden our scope to ensure that we are able not only to think “outside the box” but perhaps without a box at all.

A friend of ours who was for many years an executive at a foundation that focuses on innovation to develop sustainable communities told us about the “car mechanic principle” he used in designing groups to find innovative solutions to perplexing issues. He wanted a couple of people in the room who were not experts in any of the issues at hand but instead were wise, “on the ground” practitioners who would ask the kinds of questions that come in from left field. He said their questions often revealed problems in the (often very basic) assumptions the experts brought into the room.

When asked why he put together the national security team he did, Kennedy answered, “You can’t beat brains.” Maybe you can’t. But you also need to know what kind of brains you’re dealing with, and whether or not they work well together. For without cognitive diversity, even a brain as big as Kennedy’s will struggle to generate solutions to the world’s most wicked problems.