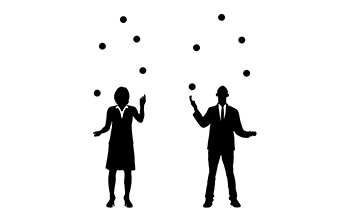

Institutional leaders often feel like jugglers spinning multiple plates, with each plate representing an urgent problem needing our attention: personnel decisions, employee conflicts, budget challenges, difficult constituents, deferred maintenance, outdated communications strategies.

This demanding exercise can absorb all of our energy as we try to make progress on each problem without letting any of the plates fall to the floor and break into pieces.

Indeed, because each problem seems so urgent, institutional leaders often rush forward to problem solving before undertaking an important prior step: problem description.

In an interview with Faith & Leadership, Jennifer Riel makes a case for the importance of problem description. Drawing on the work of her colleague Roger Martin, Riel points to a critical distinction between two types of problems -- “hard” ones and “wicked” ones.

Hard problems, she says, prove difficult to solve, often requiring repeated attempts. With enough thought and effort, however, such problems are ultimately surmountable.

Wicked problems, on the other hand, bewilder us because they frustrate our attempts at grabbing hold of them. Not only do they lack clear starting and ending points; they cross social and conceptual boundaries, and their dimensions often change the more deeply we explore possible solutions.

The 2008 economic crisis, and the particular problems it created for institutional leaders, illustrates the distinction between the two.

Consider the challenge faced by the president of a relatively small, free-standing denominational seminary: how to balance the school’s budget in the wake of the economic downturn and the associated shrinking of the school’s endowment and decline in revenues from contributions.

Defining the economic challenge as a set of “hard” problems meant that the primary issue was how to tighten an already-tight budget. In seeking solutions, several risks had to be weighed -- for example, alienating faculty and administrators whose own budgets would be cut and harming programs vital to the school’s mission.

Yet even in the midst of these difficulties, the president could envision ways forward, even if they were painful -- instituting uniform cuts across the board, cutting one entire program to preserve the rest, eliminating positions, borrowing money to cover short-term cash flow needs. None of these options was appealing, but the trade-offs were clear.

Along with these “hard” problems, though, the economic downturn created a set of “wicked” problems.

Consider the different economic models supporting the seminary, and the perplexing questions they raised.

To what extent would the current sources of financial support remain reliable in the future, especially if significant funding had historically come from a denomination in decline? How generous would the seminary’s philanthropic supporters be in light of a stock market that continued to plummet, with uncertain economic indicators for the future?

What risks were there in taking on more debt?

Would tuition-paying students still be willing to uproot their lives to relocate for school? Would a declining denomination still need candidates with the master of divinity degree for ordination, or would congregations look for other ways to supply their congregational needs? How much needed to be invested in technology, even during difficult times, to cope with the emergence of competing online programs?

Once we begin to ask questions about a problem’s wicked dimensions, we discover that those of us trying to address the wicked problems are likely contributing to the problems even as we address one or more dimensions of them. We also discover a series of further issues and questions -- and we become even more aware of the wickedness of the problems.

For example, while forecasting future economic conditions is always precarious, it now involves global trends that make gauging future economic prospects for investments even more difficult -- for the seminary itself and for its supporters.

And our economic issues spread out to broader ones: Are congregations and philanthropists as committed now, and will they be in the future, to theological education in its current form? How does the emergence of very large congregations, often either nondenominational or only loosely tied to denominations, affect the supply and demand for master of divinity graduates? How will the burdens of student loans affect people’s willingness to enroll full time in the institution? How are emerging online programs affecting enrollment patterns -- and are they a source of new funding or a potential drain on precious seminary resources?

At every turn, investigations into wicked problems trigger new questions and issues, many of which lack clear answers themselves.

The immediacy of a crisis makes it tempting to define the situation as a “hard” problem that will require us simply to roll up our sleeves and work harder.

The real creativity of leadership, however, will come when we can take a step back and acknowledge the importance of understanding our situation as a wicked problem. Leaders ought to ponder whether there are more dimensions to a problem, and perhaps better and deeper ways to frame the problem and its diverse dimensions, than we are initially tempted to think. When we do so, we are more likely to develop steps toward generative solutions.

The first step in describing a wicked problem is to live with the questions, continually sharpening and refining them until they are broad and deep enough for people to think about from a variety of angles. Because wicked problems change their shape and unfold into unexpected arenas, no single perspective can lay claim to full explanation.

The seminary president might ask questions such as the following: What deep trends will most determinatively affect theological education in the next two decades? What are the underlying drivers to our economic model, and which ones are most vulnerable to those trends? How adaptive is our budgeting process to unexpected economic events beyond our control?

Yet even when a wicked problem is thoughtfully described through a few well-framed questions, addressing it will require unconventional strategies and modes of thought.

As Riel suggests, our education typically trains us to deal with hard problems by applying various forms of analytical thinking. And we are tempted to do the same with wicked problems as well, even though our analytical habits will blind us to the wicked dimensions and constrict us to trying to solve just hard problems. We will return to trying to manage the budget rather than wrestling with the deeper issues affecting the economic well-being of the institution.

The methods needed for tackling wicked problems will involve a different kind of approach. Rather than just working harder, we will devote more attention to how we describe and define the problems in the first place. We will also spend more time on questions, probing deeply, and we will listen to different stakeholders implicated both in the description of the problem and in developing potential generative solutions. We will outline these steps in further detail in another reflection.

Wicked problems cannot be solved in the ways that hard problems can; rather, as we live with the questions, and explore possible solutions, we will design several interrelated experiments to test their generativity.

This improves the chances we will make genuine progress toward generative solutions.

Working on hard problems typically leads us to plead with others to help us. Working on wicked problems invites new kinds of collaboration -- working together, shoulder to shoulder, with key stakeholders to frame the issues and to develop new experiments. Such creative collaboration can yield fruitful, dynamic results, strengthen multiple institutions and offer new signs of hope.