Congregations worried about decline often express that concern in terms of aging participants. Findings from both the General Social Survey (GSS) and the National Congregations Study (NCS) demonstrate that people involved in congregations are indeed older. And so are clergy.

Older people long have been over-represented in American congregations because religious participation increases with age. Women also long have been disproportionately active in congregations. But unlike women, the over-representation of older people is increasing.

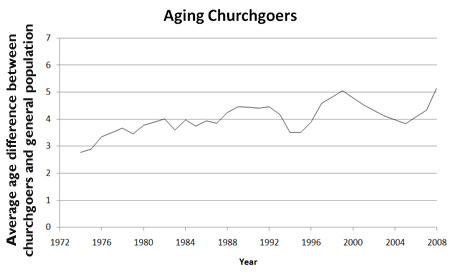

The graph above, based on 35 years of data from the GSS, shows the difference in average age between the overall adult population and adults who say they attend religious services at least weekly. The line creeps up, slowly but surely. In the 1970s, frequent church attendees were about 3 years older, on average, than the general population; today they are about 5 years older. That’s a significant change. People are living longer, and the U.S. adult population as a whole has grown older during this period, but the churchgoing population has aged even faster. Pooling the data from the 2000-2008 General Social Surveys, the average age of adults who attend religious services at least weekly is 49.6.

This aging trend also appears in NCS data. In 2006-07, 30% of regular attenders in the average congregation were older than age 60, compared with 25% in 1998. And the percent of regular adult participants younger than age 35 in the average congregation dropped from 25% to 20%. (These differences are statistically significant, as are all the numerical differences that I emphasize in my posts).

Why are congregation members aging faster than the population as a whole? Part of the answer is that young adults participate in congregations less than they once did. And this has occurred partly because today’s younger adults marry later and are more likely to be childless than were earlier generations of young adults. Married people with children remain among the most likely to be involved with congregations. Many young adults will return to congregations after they marry and have children. But recent generations return at lower rates than before – even after they form families of their own.

In some ways an aging population might be good for congregations. Some congregations have benefitted financially from the comfortable retirements of their aging members. Older upper-middle class members whose children are now self-sufficient often have more income to put in the plate and more time to spend on congregational projects. But when that generation passes from the scene, how will they be replaced? Will the generation that follows them be quite as active and loyal to their congregations? Will their retirements be as financially comfortable? We do not know, but there are reasons to worry.

It’s not just the members who are aging. Clergy are aging too. The senior clergyperson in the average congregation was 48 years old in 1998 and 53 years old in 2006-07. During those same years, the average age of the over-25 American public increased only one year. And the percent of people in congregations led by someone age 50 or younger has declined from 45% in 1998 to 37% today—a remarkable change in only nine years.

Clergy are aging across the religious spectrum, but faster for Catholics and mainline Protestants. The average age of clergy in white mainline Protestant congregations increased from 48 in 1998 to 57 in 2006-07, while in African American congregations it increased only three years.

Increasing numbers of second-career clergy and decreasing numbers of young people who go to seminary straight from college help to produce a clergy aging faster than the American public as a whole. The long-term implications of this trend for congregations, and for the clergy as a profession, are not clear.