On any given Friday or Saturday, when many churches might be empty, a steady stream of visitors heads to Holy Family Episcopal Church in Houston. Despite the bell tower and steel cross above the entry, guests may not realize initially that they are in a house of worship.

“Some people still enter and don’t know it’s a church,” said Chap Edmonson, Holy Family’s ministry operations director.

That’s because these visitors are looking for art, and they’ve come to the right place as they enter the Lanecia A. Rouse Gallery. Inside, an attendant offers a guest book and materials about the current show. To the left, a bright airy space is carefully curated with art. Narrow windows illuminate the gallery’s white walls and polished concrete floors.

The nave rests just behind the welcome desk — and, as Edmonson explained — sometimes visitors, only after poking their heads through and seeing the waiting pews, ask if they are in a church.

“It happens all the time,” he said, smiling. “And it’s really cool.”

Edmonson encourages them to tour the building, since the artwork does not end with the gallery. Nine large abstract paintings by Rouse, the gallery’s namesake and the church’s artist-in-residence, grace the sanctuary, back hall and offices.

The paintings were commissioned by the vicar, the Rev. Jacob Breeze, before there were walls for hanging them, when the congregation was just being planted and members met in living rooms to shape a vision. The goal was to create “a church for people without a church.”

Breeze would ask those who gathered in his home, “If we do this, would it be a church you’d be proud to be part of?”

He told them to keep that simple tenet in mind as they dreamed big.

“Let’s design a church we would be proud of and just bet on that,” he said. “Let’s bet that other people will be excited that it exists. Let’s design ministries that we would want to be a part of ourselves.”

That prophetic charge would lead Holy Family on a distinctive path with art at its heart. Moving forward, the congregation would develop an art collective, regular creative workshops and arts-related community events.

In time, members would give new life to a building, transforming it into both a gallery and a church, making Holy Family a hub for arts and theology in Houston funded through a combination of congregational giving, grants and support from the Episcopal Diocese of Texas.

Breeze said he does not consider art to be a ministry, but rather ministry to be an art, a medium, just like music, dance, painting or drawing.

“Church should be a place where we help inspire people to be their most creative selves,” he said. “And we ought to be generating some of the most beautiful art in the world.”

Art from the start

As a child in Illinois, Breeze was immersed in painting, drawing and dance. In high school, he turned to musical theater and formed bands with friends.

In what ways do the design and atmosphere of your worship space reflect the creativity of your ministry?

“The earliest way I self-identify in life is as an artist — and it still is to this day,” he said. “I say that I’m an artist, theologian and priest, in that order.”

Breeze’s inner artist was integral to planting Holy Family in 2016. He moved to Houston after graduating from Duke Divinity School and serving a United Methodist church in North Carolina.

Holy Family began as a UMC plant but left the denomination after a period of discernment when Methodists were in the midst of a years-long debate over same-sex marriage and the ordination of LGBTQ clergy.

On the Second Sunday of Easter 2019, leaders from the diocese and Houston's Chapelwood UMC gathered together to bless Holy Family as a new church plant in the Episcopal Diocese of Texas.

Through the Rev. Andy Noel, Breeze had partnered with Chapelwood, which helped resource the early days of Holy Family. Breeze credits Chapelwood’s generosity and history of starting new communities of faith as instrumental for the new church.

“I started from absolute scratch,” Breeze said. “It started with me following the Apostle Paul’s method of just hanging out with people. I focused on connecting with artists immediately and trying to be friends with my barbers and baristas.”

Whether pouring a latte, cutting hair or painting a canvas, creatives all work with their hands. “It gives you the ability to talk all the time, to be friends and to be friended,” he said. “And that’s what happened.”

Breeze soon assembled a small group that started meeting every Sunday at his home. He didn’t consider the participants to be simply members, but instead charged them to be future leaders, helping each create a house group of their own.

At the same time, Breeze leaned into what he considers one of the original duties of the church — patronizing the arts. He looked at numerous examples in church history and thought, “Let’s do that. Let’s move money into artists’ hands.”

He began renting spaces for artists to exhibit and commissioning some to create pieces for Holy Family.

“It ended up being an amazing collaboration,” he said. “There’s been so much fruit that’s come of it.”

Before the church had a home, Breeze acquired vessels for the Eucharist and a set to carry communion to the homebound by artists Ellen Cline and Abbie Preston Edmonson.

How can you reimagine ministry as a form of art? What possibilities open up when you approach our work as creative expression?

He worked with Kyle Tueffert on the ambo, processional cross and first altar, and then with Lee Denson, the woodshop manager at St. Luke’s United Methodist Church, also in Houston, to build a second altar.

Rouse was one of the first artists Breeze commissioned. The two met over coffee in 2016, initially connecting because both had attended Duke Divinity. Rouse, the daughter of a pastor, pursued ministry before her path led to art therapy and then to pursuing art full time.

“She’s an amazing person, an amazing artist, and was up for collaboration,” Breeze said.

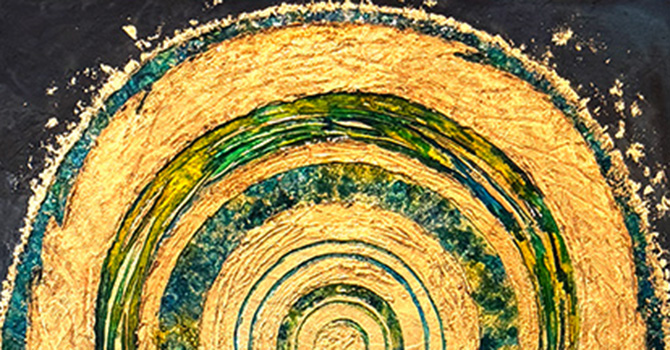

He envisioned Rouse creating paintings that act as paraments, the traditional hangings and ornaments that adorn the sanctuary to signify a liturgical season. “I dumped everything on the table that I wanted theologically,” he said, asking her to interpret in her own abstract style.

“He shares his vision and invites you along,” Rouse said. “And he asks, ‘What is God stirring in you?’”’

Creative ministry

The collaboration evolved, and Rouse’s role as artist-in-residence has included leading workshops and heading an artist collective. The group met monthly at Rouse’s studio for meditative and creative exercises, as well as for camaraderie and support. After a year, Breeze rented a space for an exhibition of their work.

Chap Edmonson was in the first cohort, before joining the church staff or becoming a member of the congregation. Attending art exhibitions hosted by Holy Family is what first brought the filmmaker to the church.

“I loved how Holy Family held faith and the arts together,” he said. “That resonated with me. That really pulled me in.”

Being part of the collective was a game changer, helping Chap Edmonson move his films into a more artistic realm.

“The idea was to create for the sake of creating — without a deadline,” he said. “When you’re around people who also feel things the way you feel them, it’s just life-giving. I was able to channel creative ministry in a new way, to tell stories I wanted to tell.”

Hailie Durrett, now digital marketing coordinator for Holy Family, was a member of the 2020 collective. She had attended the church for about two years, and while she enjoyed taking photos, did not yet consider herself an artist. Then came a surprise invitation from Rouse.

“When Lanecia asked me, I was floored,” Durrett recalled. “I would say that it was life-changing and identity-shifting.”

Rouse also organized community dinners, meals created in collaboration with chefs, artists and musicians. She led two events before COVID, and Edmonson recently reinstated them.

He now also leads the artist collective, able to share with others an experience so meaningful to him. “I have been able to help others. It does feel so full circle,” he said.

The church’s front porch

Holy Family first gathered for a public liturgy on Ash Wednesday 2017; Rouse revealed her first commissioned painting then. Eventually, the congregation began worshiping at a venue called The Space HTX. When COVID struck in 2020, during Lent, services moved online, and membership grew.

“We really met so many new people,” Breeze said. “We knew eventually we’d be on the other side of this pandemic, and we’d need to gather again.”

The diocese identified a building on Houston’s East End; Breeze learned that the space would require vision. “But what better congregation than ours to have imagination?” he asked.

The nearly 100-year-old, 9,000-plus-square foot building was dilapidated at best, abandoned for years. One of the first calls he made was to Durrett.

“Hailie gets what this organization is,” Breeze said. “She loves God. She loves this church, and she has great taste.”

Durrett chaired the renovation. “I got my first hard hat and started leading construction meetings,” she said.

The building had been a grocery and a meat-packing warehouse. With no windows, rolling garage doors in the entrance and a floor sloped for drainage, the site presented several challenges.

“We joked that we could have sold tickets to a haunted house,” Durrett said, laughing. “It was horrifying.”

The first step was assembling a dream team. Architect Hill Swift, who headed the 2002 renovation of Houston’s Trinity Church, leading the way. Forney Construction served as general contractor.

“They had worked with a lot of churches and nonprofits before, they understood our budget, and they helped us get creative,” Durrett said. “They knew our priorities were to create a place for worship, a place for gathering, a place for art.”

The floors were leveled, and windows and skylights added for light. A minimalist, modern style emerged. For Breeze, finding talented craftsmen for the project felt like another creative collaboration.

Art would be featured throughout the building. A concrete baptismal font became a focal point in the nave, as well as a sturdy communion table, both crafted by Del Gunnells.

A niche was carved in a nearby wall to hold a handmade ciborium. Church pews, the front lobby desk and a long bench in the gallery were hewn by Alexander Lohn.

Then came the gallery. “I just don’t think we could have a building without a gallery,” Chap Edmonson said. “It’s part of the core of who we are.”

The idea to name the space after Rouse seemed obvious. “The partnership with Lanecia was so epic,” Breeze said. “There was never a question about whose name we should honor.”

The Lanecia A. Rouse Gallery, or “LAR Gallery,” officially opened in April 2022. Durrett calls it the church’s “front porch.”

How might your faith community bring new life to some thing or place that has been abandoned or discarded? What are the opportunities for engagement and innovation?

Rouse now serves as the gallery’s head of curation, working with a team to organize six to eight shows annually, as well as opening receptions and artist talks.

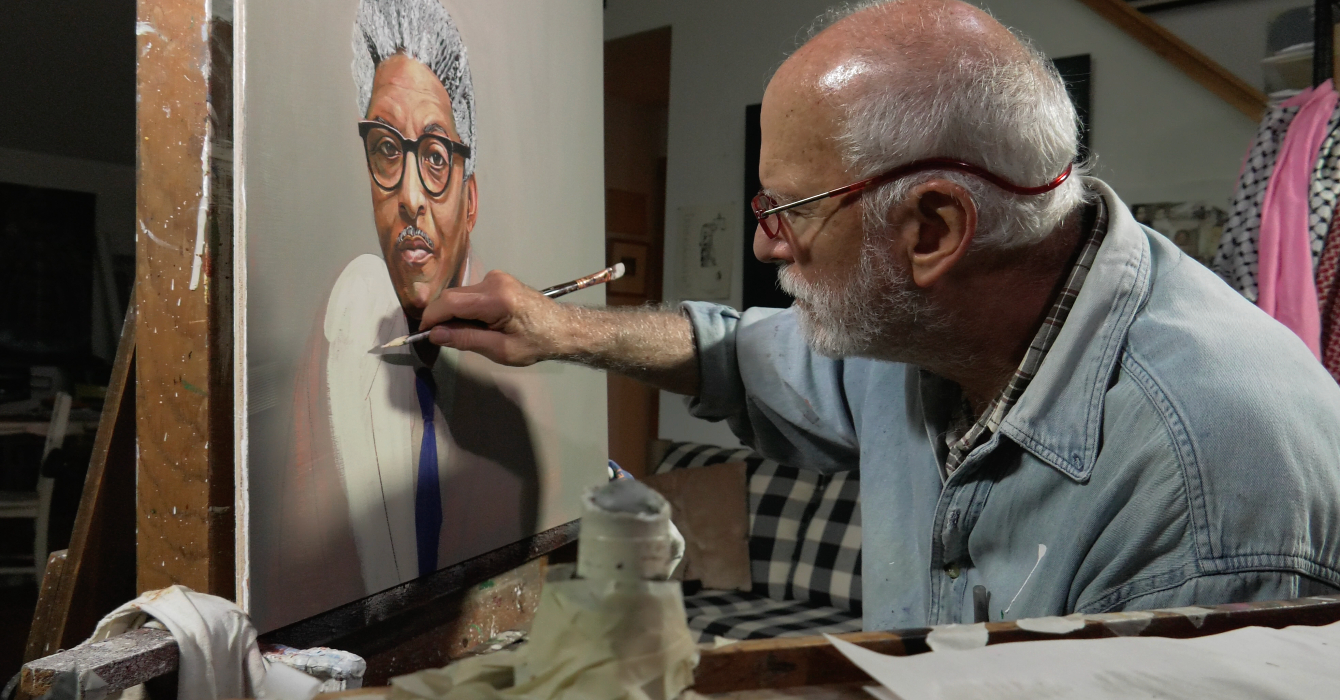

In its first year, the gallery exhibited abstract paintings by Bruce Herman, mixed media creations by Anthony Suber and poems combined with threadwork by Sara Triana. Since then, the venue has showcased paintings, installations and sculptures, as well as group shows by the artist collective and from a children’s art-based summer session.

The LAR Gallery considers the artists partners.

“This is a space where they can do that dream project,” Rouse said. “It’s a space that welcomes the artist exploring new expressions of questions that they are contemplating in their work, and we’re willing to ride with you in that process. We want the process to be a generative, life-giving experience for the artist and for the people who come into this space.”

The current exhibit displays the photographs of Houston artist Brian Edwards Jr., known as Brian Junior. The solo exhibition, “On My Way Home: Everything the Light Touches,” documents the African American cowboy experience, from ranching to rodeo.

The series is an homage to Edwards’ rural hometown of Dayton, Texas, a place he came to appreciate only after leaving to pursue bigger dreams.

“You realize home is the true place of solace for you,” Edwards said. “This is my love letter to the community. And it has a parallel story. Those people brought me back to life.”

Rouse explained that the curation team is guided by the liturgical calendar. Edwards’ photographs speak to Lenten reflection and returning, as well as to Easter’s promise of new life and resurrection.

“Through his camera, the light catches every gesture, every moment of vulnerability, rest, joy, strength and labor,” Rouse said. “The light touches the connection between horse and rider, people in the community, the land and sky. It bears witness to human endurance, and the ways histories live on in us — helping us find our way home to ourselves.”

When the LAR Gallery initially reached out to Edwards, he was unfamiliar with the venue. After looking it up, he headed to an opening and was pleasantly surprised to find it packed.

“They function just as any other prominent gallery,” Edwards said. “They have the talent. They have the knowledge. They have the education and the resources.”

Since his work has a spiritual undertone, he was intrigued by the gallery’s tie to faith. From the first meeting, he noticed something special in the venue’s administration.

“They had this level of sincerity and care,” he said. “They were trusting, and they were very hands-on.”

Edwards has made a point to regularly drop by and talk to gallery visitors since the show’s opening on Feb. 28. He recently went on a Sunday before church and watched as a 3-year-old girl walked around the space before heading into worship. “She literally looked at every photo,” he said.

What are new and different ways that seasons in the church year, like Lent and Easter, might be presented through art within your worship space?

Edwards is convinced that the LAR Gallery is contributing to Houston’s art scene. “I’ve seen them bring in some really heavy hitters, people who are doing great things in the community,” he said. “It’s a phenomenal space in a city that needs more spaces.

“They amplify a lot of voices. They’re extending the love of God to so many people. If you want to see good art, it’s going to be there. But if you need care and kindness, love and embrace, it exists there too.”

Adding beauty to liturgy

Kristie Beeler has been a member of Holy Family since 2017 and served as senior warden during the building's renovation.

“They wanted to be a church for people without a church,” Beeler said. “I liked the mission of reaching people who had been hurt by church, or who had never been to church or who didn’t like traditional church but wanted some kind of community.”

She recalls when Rouse’s paintings became a part of worship. “I would take communion and go over to the painting and just meditate,” Beeler said. “It brought contemplation and beauty into liturgy, which was something I hadn’t really experienced before.”

It’s a practice she continues today in the East End building, where another of Rouse’s paintings hangs over the baptismal font.

Not acting as a gentrifier was a priority for Holy Family, Beeler said. Members took time to learn about the neighborhood, go to the local businesses and be intentional about landing in their new home.

“It’s nice to have a place where you can build roots,” she said.

Two years later, the parish has 400 active members and a staff of 13. Area residents come to gallery shows and church services, and local nonprofits use the space. An independent bookstore also hosts artist talks there.

“The building should be available not just for us, but for the entire community,” Beeler said.

In a city that typically tears down its old structures, Chap Edmonson said that neighbors have thanked Holy Family for saving the building.

“There are so many stories that are erased,” he said. “This space has been brought back to life — and part of that is the beauty that comes out of this gallery. There is new life that comes from imagination and creativity.”

Holy Family’s interior, which resembles meditative spaces like Houston’s Rothko Chapel, can make a world of difference for those who have experienced church hurt and might shy away from a more traditional interior, Beeler said.

In what ways could art inform liturgy and liturgy inform art for your faith community?

She believes that the gallery also makes the church more accessible to those who might not otherwise step foot on campus. At the same time, churchgoers gain greater access to the arts.

“I feel like it makes art more approachable,” she said. “Even kids get to be close to art at a gallery, and that’s super cool.”

Her experience with Holy Family has changed how she sees art in general.

“There’s a reverence, a spirituality that comes into the art, because they’re so tied in my mind now,” she said. “Admiring art and seeing beauty in art is a spiritual practice.”

Breeze said that artists do not simply decorate the church. “They reveal her depths. At Holy Family, we don’t use art as ornament; we tend it like fire.”

What is God stirring within you that invites a creative response in your ministry? How might you give shape to that vision in new or unconventional ways?

Questions to consider

- In what ways do the design and atmosphere of your worship space reflect the creativity of your ministry?

- How can you reimagine ministry as a form of art? What possibilities open up when you approach our work as creative expression?

- How might your faith community bring new life to some thing or place that has been abandoned or discarded? What are the opportunities for engagement and innovation?

- What are new and different ways that seasons in the church year, like Lent and Easter, might be presented through art within your worship space?

- In what ways could art inform liturgy and liturgy inform art for your faith community?

- What is God stirring within you that invites a creative response in your ministry? How might you give shape to that vision in new or unconventional ways?