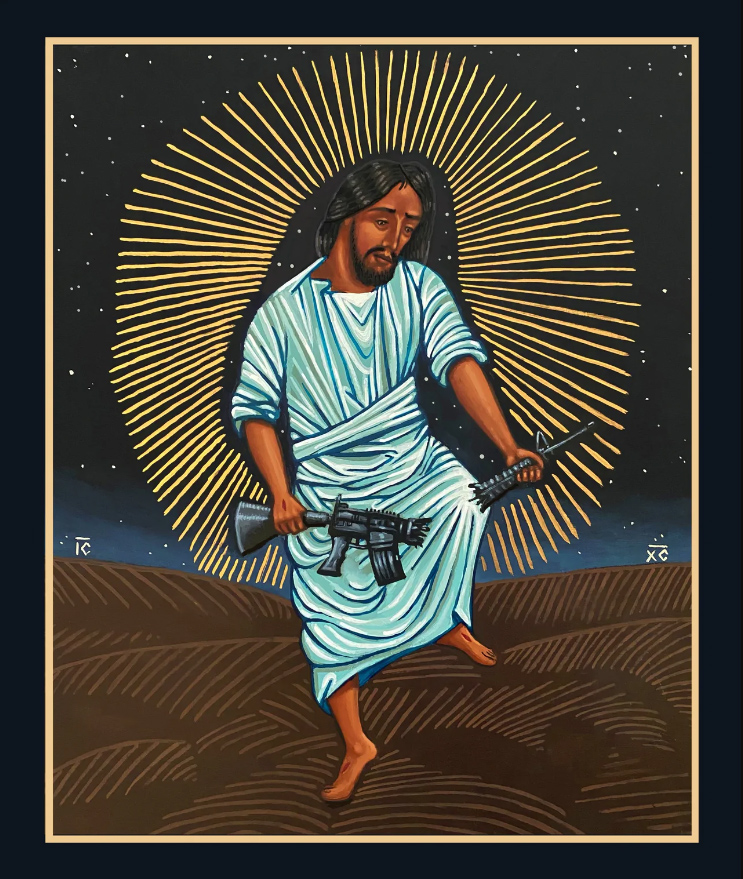

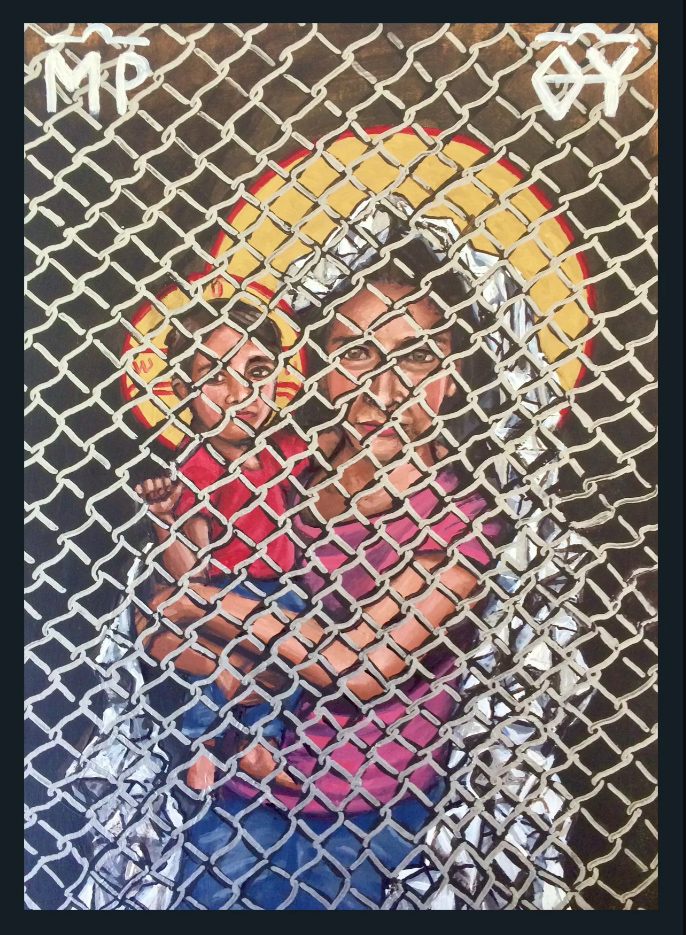

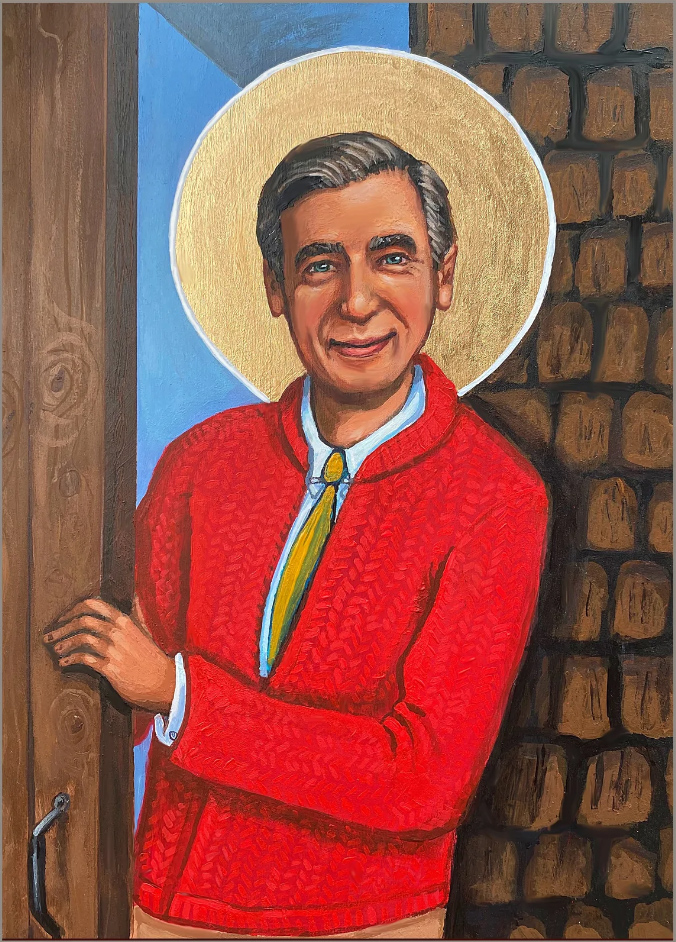

Kelly Latimore is a St. Louis-based artist who specializes in painting icons. Some of his images have attracted widespread attention, as when he faced death threats over “Mama,” his Pieta-style image of a Black Mary cradling the body of Jesus, who resembles George Floyd. Others depict figures such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Pauli Murray and Mahalia Jackson. One, “La Sagrada Familia,” shows the holy family as modern immigrants walking in the desert.

Latimore spoke to Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne about his work. The following is edited for length and clarity.

Faith & Leadership: Can you talk about how iconography grew out of your collective work for connectedness as a member of a monastic community?

Kelly Latimore: I’m a PK, a pastor’s kid, and I grew up in a small Protestant denomination. It was very much about transcendence. Later in life, after graduating [from college], I ended up in Athens, Ohio, and was a part of this small monastic farming community. The main mission of that place was growing vegetables and food for food pantries. Volunteers would come to the farm and help in that work, but also people who were poor and living in shelters, coming and joining us in that work as well.

Putting your hands in the soil and weeding a bed of carrots across from a complete stranger, and the conversations that came out of that — I really learned that the way we use things in the world is of spiritual significance. It was a transition away from transcendence. It was more about engaging God in a physical incarnation in the world.

It was less about transcendence and more about engagement, embodiment and communion, connection. And so it was a very profound time. The first icon that I painted was called “Christ: Consider the Lilies,” and that stemmed out of my relationship with my best friend, Paul. We used to talk about a lot as we were growing food: How do we as farmers have a right relationship with the earth, and how do we, as Jesus would say, consider the lilies of the field? What does that mean?

I had done a lot of traditional icons; I started how all iconographers start, going over these old images and tracing them as best I could. But then when I got to a point where I wanted to try my first original icon, it was that idea of “Christ: Consider the Lilies,” and it focused on our common work. And what was interesting — it wasn’t a great first. It was a good first try. Christ, if you see it, he’s almost surprised that the lilies are in his hands, and the lines are shaky.

But what was interesting about it, and I think what was beautiful, was that the community embraced it, because it was a part of our common experience. It showed me how art can be a focal point for focusing and seeing in a new way how we want to live in the world. As time’s gone on, this has been the theme of the work that my partner, Evie, and I collaborate on.

Trying to find the holy family that is among us here and now or Christ that is in our own neighborhood, and bringing these modern images of people that are struggling or in pain right in front of us but inherently have the image of God within them: the refugee, the immigrant, those in prison, those suffering from living in tent cities.

There’s another icon I did called “Cloud of Unknowing.” In my early days in iconography, I had started an icon called “Christ the Pantocrator” or “Christ the Teacher,” which is a pretty traditional icon where Christ is holding the Gospels and holding a blessing hand. I got really frustrated. His face was fine, but his hands weren’t right. And I ended up putting it up on a shelf, where it sat for two years.

And then at one point I had gotten some new gold leaf in, and I was looking for something to try it on, and I found that icon and was like, “Ah, I didn’t really like this anyway,” so I just started gold-leafing over it. But I realized that because I had reworked that icon so much, the paint stood up, even with the gold leaf [over it]. It looked like a gold leaf board, but if you got up close, you saw the raised face of Christ.

I had two priests that are friends of mine, and I was showing them what I was working on, and they saw it and both said at the same time, “That’s ‘The Cloud of Unknowing.’”

The 14th-century work is about [our] potential for knowledge, or knowing God — that the more we put God under a cloud of unknowing, or a cloud of forgetting, the closer we’ll be to God through our hearts and through our experience.

My friends, those priests, named what that image was, and therefore it became a new gift. I think that’s what art can do for us in our communities. It should teach us how to see in new ways, not only to show how similar we are, but also [to name] the racism that might be within me or to name the ways that I’m not loving my neighbor well or other ways that maybe I’m not seeing God as clearly in my neighbor and around me.

An artist’s life is to be more present. For my partner, Evie, and I — and Evie is a big part of the work — we’re just trying to be present to what is going on around us. But for me, all of this artwork doesn’t really mean much without the relationships that make life worth living. And I think that’s so beautiful about iconography; it’s a very communal art.

As an artist, I’m entering into this improvisation or this dialogue, which I think doesn’t happen in a lot of artists’ work. Working on this artwork with churches can be very hard. But what is so gratifying and is a gift to me is that part of the work: the communality, the conversations about images that mean something to them and that want to push them toward communities and push them toward new ways of being in the world and new ways of relating to one another. I wouldn’t be able to enter into that if I wasn’t doing specifically this work, and so I think it’s just about receiving those gifts and doing the best I can to translate that gift [of communality] into the work.

We are just constantly inundated with images. What happens, especially with the social media world, TikTok, Instagram, whatever, is that we can be so quick to speak into something. I hope my art has this potential to teach us to not speak into something but just to learn how to observe, to be still and observe something. And that’s my hope for these images, that they can potentially create dialogue. Not only an internal dialogue but also a dialogue between each other. And that just observing and not speaking into something, I think, is the first part of connecting to the piece of art, whether it’s art in churches, in this iconography or elsewhere.

What is our church art for? Is it glorified wallpaper, or can it be something that can help us see each other, see in new ways and see God in new ways?