When she enrolled at Columbia Theological Seminary, it seemed to Lisle Gwynn Garrity that everyone but her had received a divine call. She had ended up there almost by accident, after accepting a partial scholarship intended for college graduates who had never considered vocational ministry but might have a talent for it.

“I was there because I said yes to an opportunity that I didn’t think I could say no to,” said Garrity, who was awarded the Ministerial Challenge Scholarship — an invitation-only opportunity for graduates of Davidson College — as she was finishing up her English degree. “It was bizarre to constantly feel, ‘What am I even doing here?’”

While her college major had focused on literature, Garrity’s passion was art, and she’d spent much of her free time as a “groupie” in the art studio at Davidson, a Presbyterian liberal arts school outside Charlotte, North Carolina. She also interned at Davidson College Presbyterian Church, once accompanying her mentor, the Rev. Shelli Latham, to a summer youth gathering at Montreat Conference Center, where Garrity live-painted while Latham gave her keynote address.

“I have no idea what I’m doing in my life right now,” Garrity recalls thinking, “but this feels like I was created to do this.”

While at seminary, she painted once again in front of a live audience during another Montreat conference. And it was then, Garrity said, that it dawned on her: perhaps this was her ministry.

“I just started chasing that ‘aha!’ — that deep, deep inner knowing I’d feel when creativity and art intersected with faith,” said Garrity, who describes herself as a “pastorist” (pastor + artist).

That chase led Garrity and a small group of like-minded women to found A Sanctified Art, a ministry that offers creative worship resources, including original artwork, poetry, films and music, to pastors and faith communities. A Sanctified Art’s six-member creative team collaborates with guest artists, authors and musicians — many of them seminary graduates, church leaders and theological scholars — to create everything from banners and children’s bulletins to devotionals and sermon-planning guides.

Garrity describes the creative process as similar to faith formation: pursuing a vision, stepping into the unknown and trusting the process, wherever it leads. But generating a thematic worship series or an art installation is time consuming, putting it out of reach for busy clergy who are also trying to provide meaningful pastoral care.

How might church be a place where people discover what they are created to do?

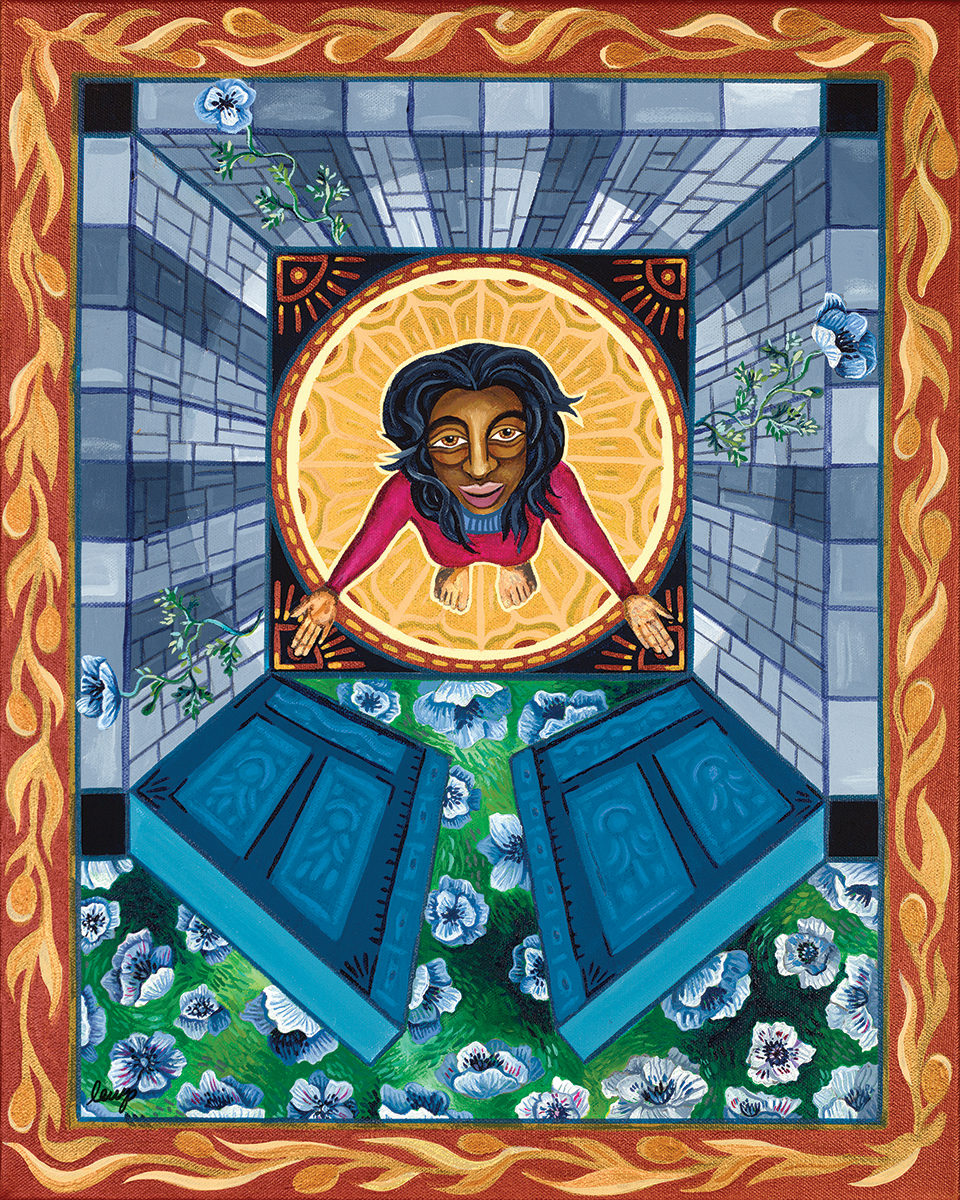

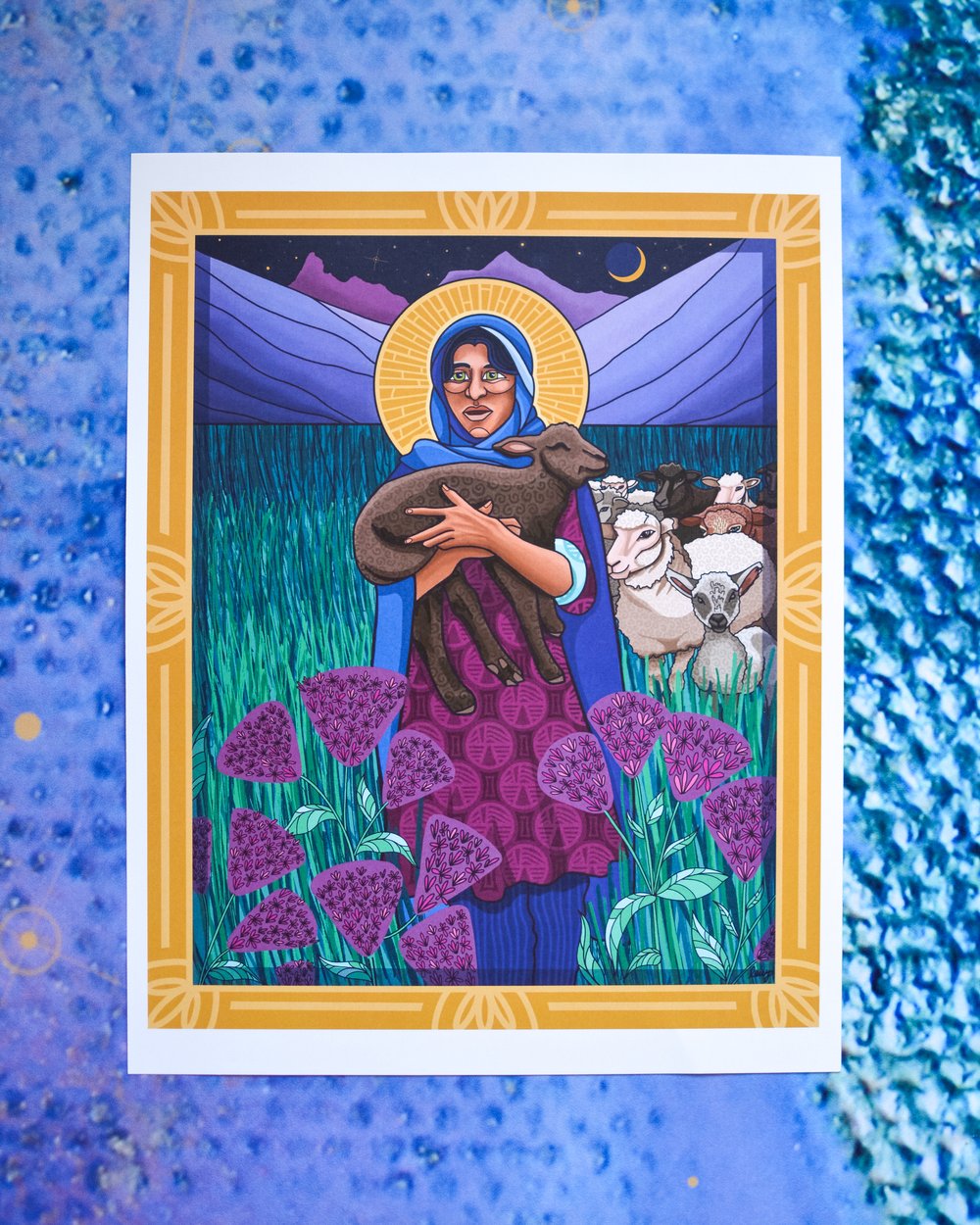

Pastor Kristen Capel of Nokomis Heights Lutheran Church in Minneapolis knows that challenge well. She and several other creatives with church backgrounds founded a ministry of inspirational material for pastors years ago, she said, but as each of their lives got busier, that project fell by the wayside. Not long after that, she stumbled upon A Sanctified Art. Capel has found the variety of materials and the diversity depicted in the artwork “life-giving” for her bilingual congregation, which serves a large population of immigrants and asylum seekers from Latin America, she said.

Hospitality and creativity are core values at Nokomis Heights Lutheran, Capel said, and she has adapted the artwork and poetry from A Sanctified Art primarily for Bible study and worship. Her church has displayed some of the ministry’s images in its courtyard, where she sees parents and children stop to explore and discuss the work. One of their favorite activities is to look at a piece of art during Bible study and try to guess which scripture it’s linked to before enjoying the “reveal” in the artist’s statement.

“For me, it provides a creative spark, along with some really great concrete materials that we use to adapt for our context in ways that make sense,” Capel said. “What we found in a bilingual community is that art, music, lighting candles — activities where you engage all of your senses — are more universal, and they don’t need translation. The thematic stuff [from A Sanctified Art] coming during the seasons helps people have a common language that feeds a community, and that’s really sacred to people.”

The aim of each poem, song, mandala or other creation is to engage the faithful in ways that “widen access to God,” according to A Sanctified Art’s “We Believe” statement. Five of the organization’s six staff members are ordained, and the sixth is currently in seminary. All of the work produced is theologically grounded and includes an artist’s statement and the verse that inspired it.

It isn’t commercial art, Garrity said, and the materials in the group’s library aren’t meant for passive consumption or church decoration; rather, they’re meant to help time-starved pastors nourish the souls of their flocks while sparking creativity in worship and inspiring meaningful conversations.

Traditioned Innovation Award Winner

Leadership Education at Duke Divinity recognizes institutions that act creatively in the face of challenges while remaining faithful to their mission and convictions. Winners received $10,000 to continue their work.

“Our hope is it’ll be like a visual proclamation. We all approach it like we’re preaching a sermon — it’s just a visual one,” Garrity said. “We’re always asking, ‘What do people need to see?’ And we’re just doing our very best to answer that.”

Seeing the art ‘come alive’

When Garrity graduated from seminary in 2015, she felt she might have the skills to lead a congregation, but the thought of serving as a church pastor made her heart sink.

“I refused to put myself in a box I knew I didn’t fit into. That felt like a betrayal of my calling, to go on a path I wasn’t right for,” she said. “I thought, ‘I have to find a way to merge this art and spirituality and creation — there has to be more here.’”

She was right. Her calendar filled up with invitations from churches to lead weekendlong arts retreats or to live-paint alongside a sermon. She began to wonder: What if faith communities had access to a steady source of sacred and affirming artwork? How might worship be shaped by that? Her vision, she said, “was easier to feel than to describe.”

“But I knew it was up to me to steward it or it would find a different vessel,” she said.

In what ways does your worship “widen access to God”?

After sharing that vision with those closest to her, Garrity found she wasn’t alone. Fellow Columbia Theological Seminary graduates Sarah Are Speed, a writer and poet, and Lauren Wright Pittman, a graphic designer and artist, helped Garrity found A Sanctified Art, along with her sister-in-law Hannah Garrity, a Cornell-trained artist and former educator. All of them viewed creativity as a spiritual practice and were trying to find a way to mesh that with ministry.

They quickly created a website and a tiered pricing structure; congregations were encouraged to contribute toward materials in accordance with their size and what they could afford. In January 2016, they posted their first “bundle” of creative resources for Pentecost. About 50 churches requested those early digital materials. They now handle about 7,000 orders annually from faith communities around the globe.

Congregations are encouraged to adapt the resources for their own faith communities and then share what they’ve done on the group’s Facebook page. Garrity said it’s gratifying to see what happens when A Sanctified Art’s creations are “set free in the world.”

“It’s so incredible,” she said, “because we remember when this theme or series started as a phrase someone spoke in a brainstorming session. And then it becomes a Google Doc with 10 pages of notes. And then it keeps evolving. And then we get to see a church in Australia bringing it to life. It’s so immediately fulfilling to see it come alive.”

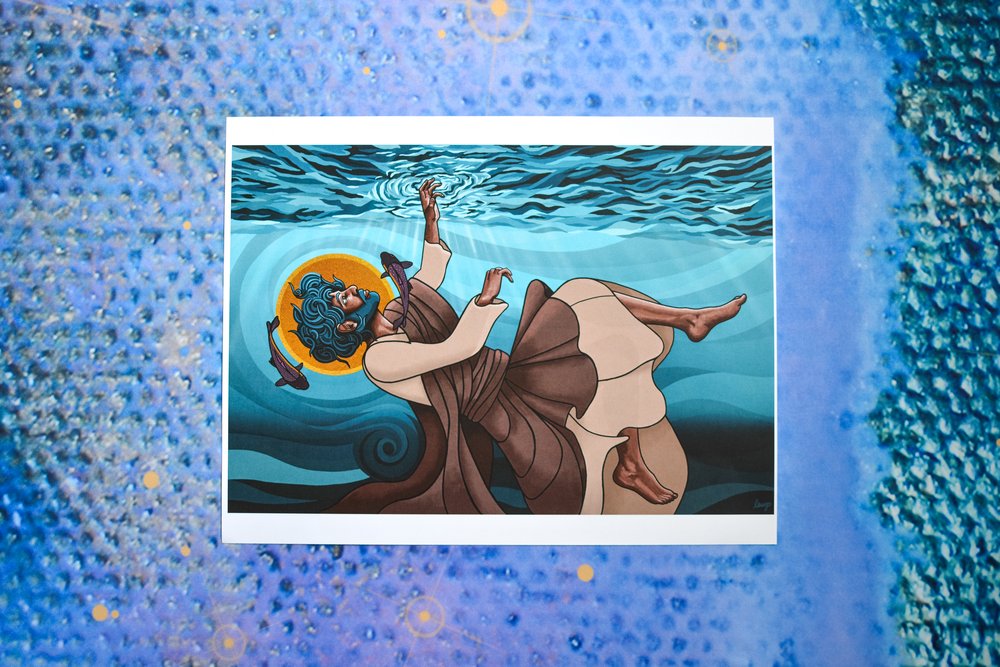

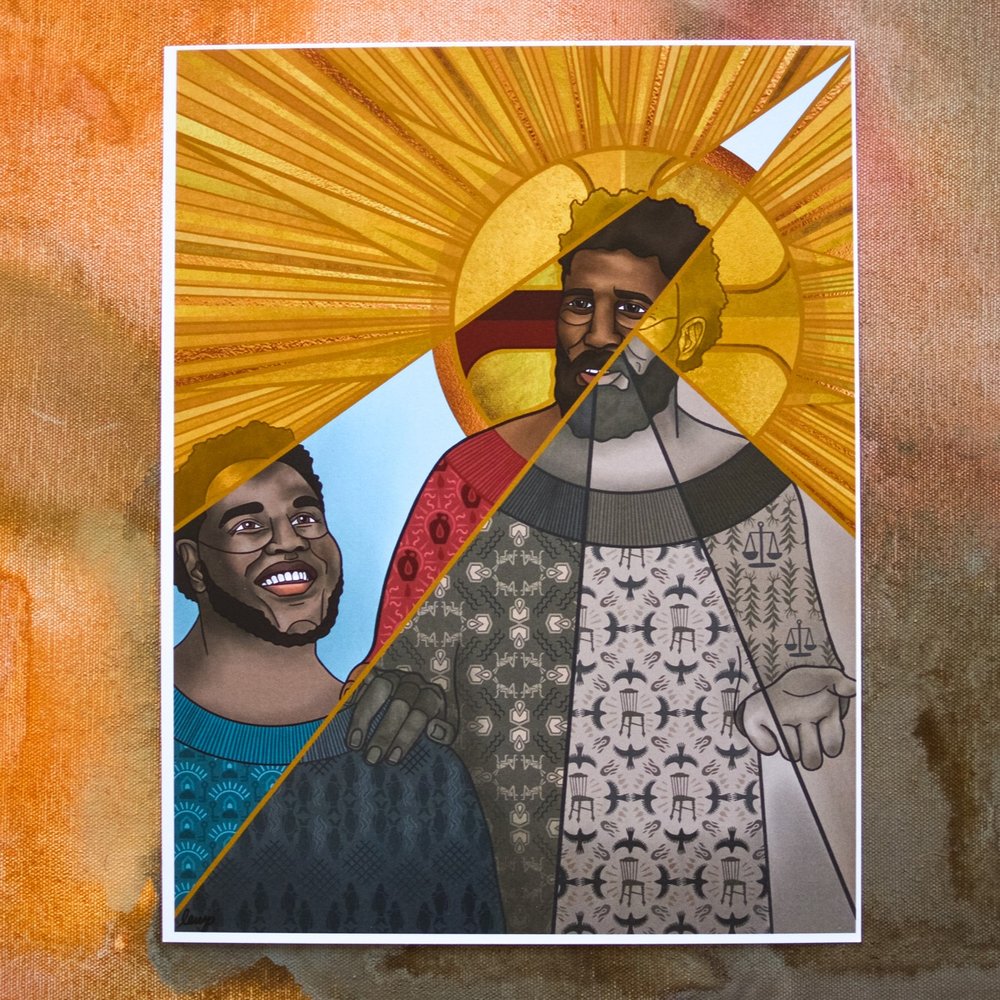

A Sanctified Art’s team generally prepares months in advance for a liturgical season, teasing out themes from the biblical text that resonate with them. “Wandering Heart,” the theme for their most recent Lent and Easter package, explored Peter’s journey as a disciple of Jesus.

Last year’s Advent series, “How Does a Weary World Rejoice?” centered on the stories in Luke’s Gospel and drew parallels between Christ’s birth during a time of despair and today’s struggle to find joy amid global distress.

“Unraveled,” released in 2019 as a series for any season, asked worshippers, “What happens when our world falls apart?” The popularity of that series exploded months later when the pandemic struck.

“Theme planning is a both/and, with one fist clenched around the ideas we feel compelled by and one hand open to the ideas we haven’t had yet or that others have,” said Garrity, whose team meets virtually, since they live all over the country. “It’s a push-and-pull, a give-and-take, and over the years, we’ve developed a good balance in our core group.”

While initial offerings were produced solely by A Sanctified Art’s founders, the group started partnering with guest creatives by 2019. Those contributors receive flat-rate honoraria and maintain ownership of their work, while A Sanctified Art licenses the creations, usually for a liturgical season.

Starting in 2020, as the project became more financially sound, A Sanctified Art began donating a portion of each season’s revenue to causes recommended by their guest contributors. Thus far, they’ve donated nearly $60,000 to organizations supporting racial and economic justice, disaster preparedness, and assistance for refugees and LGBTQ+ communities.

Does your community hold space for ideas you haven’t had yet?

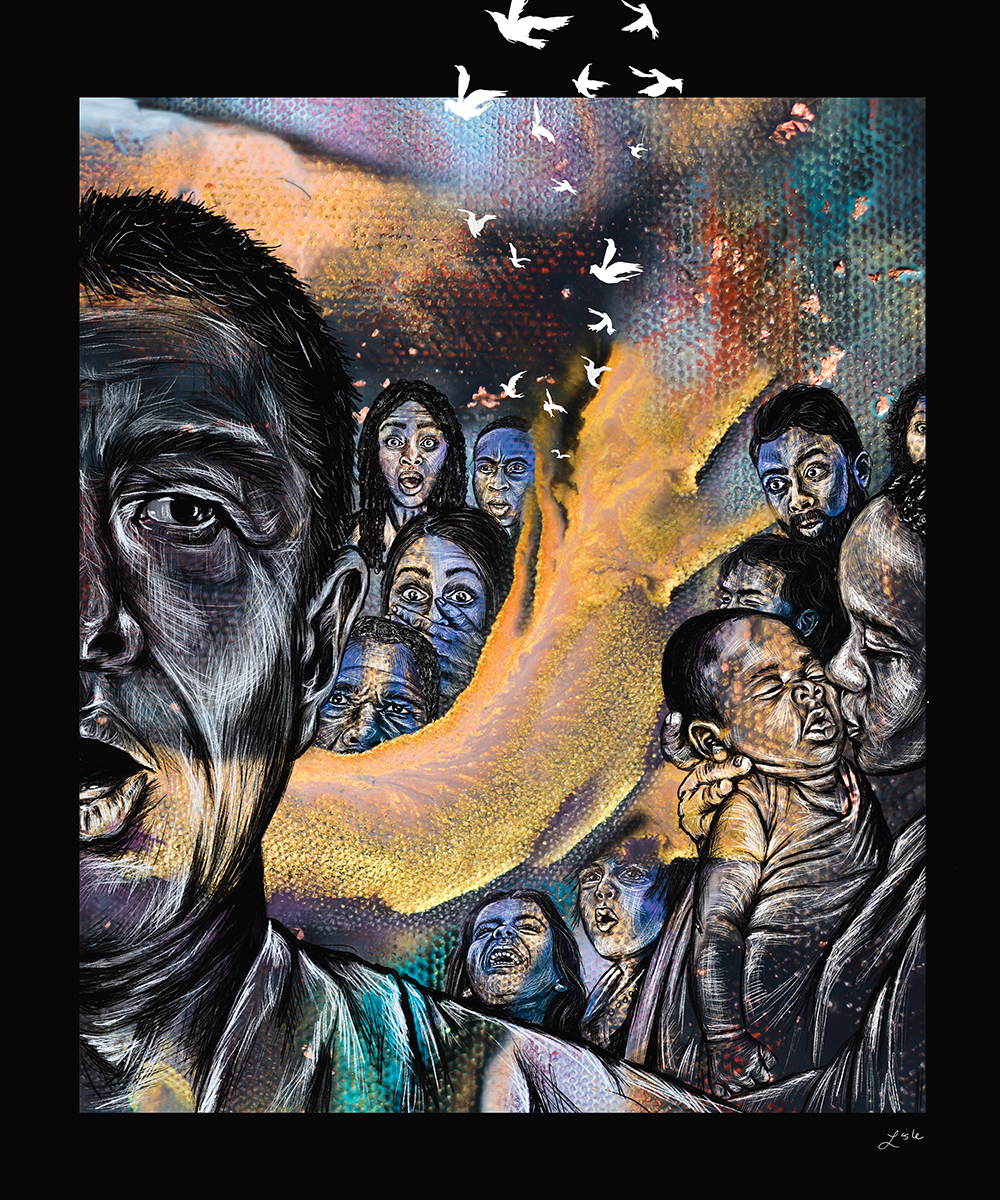

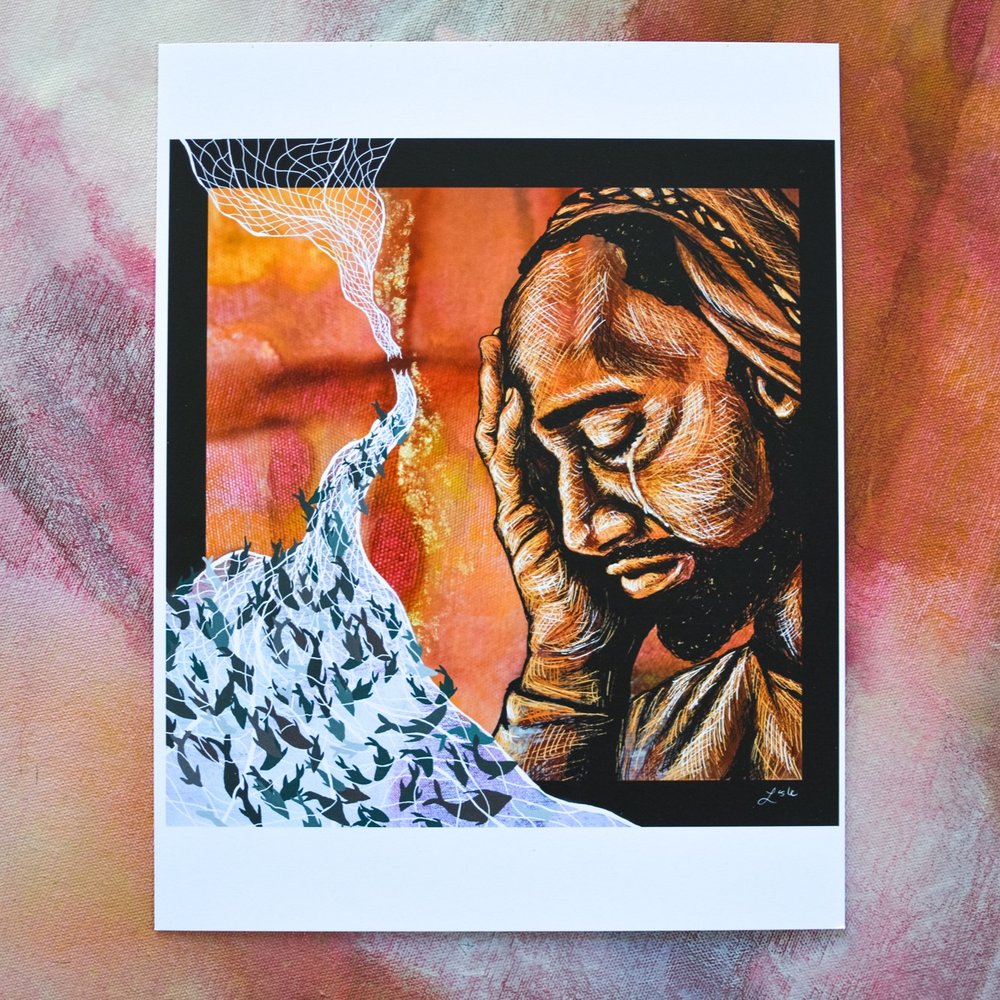

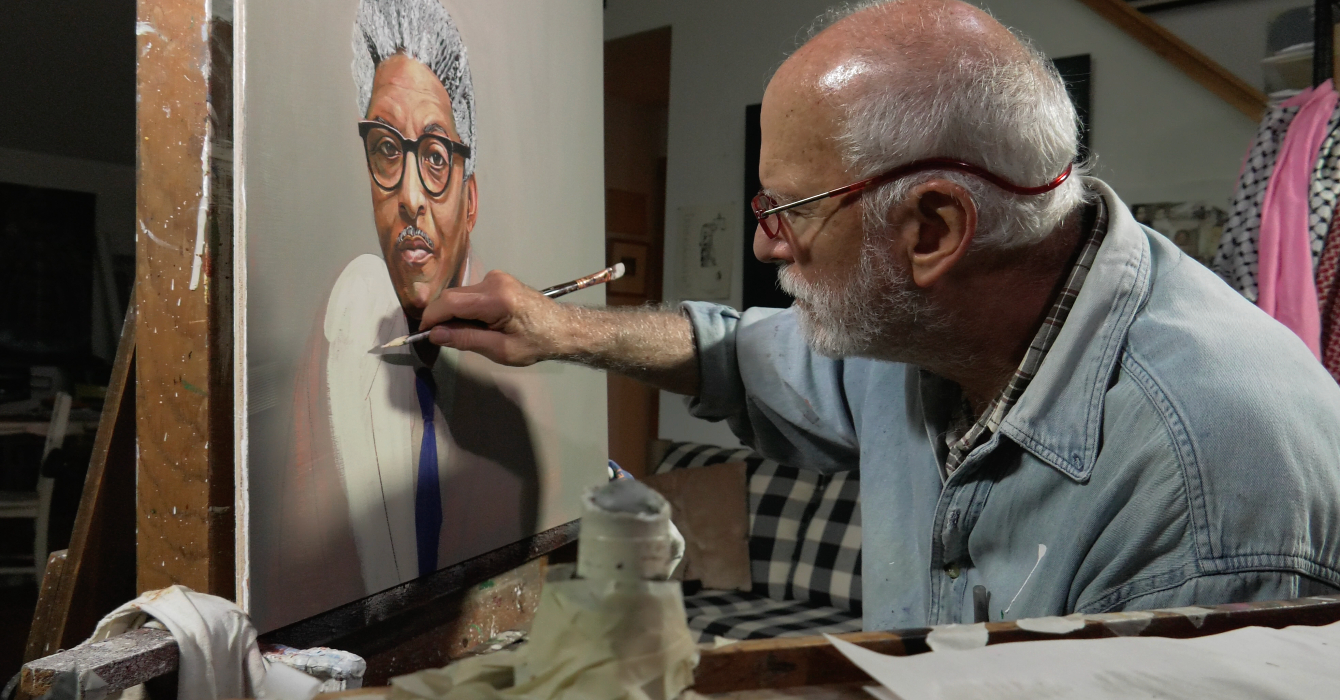

The Rev. T. Denise Anderson, a visual artist and the director for Compassion, Peace, and Justice Ministries for the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), began collaborating with A Sanctified Art in 2021 for its Lenten series “Again and Again.” Her original diptych “Pietà: Woman, Behold Your Son; Behold Your Mother” drew parallels between the grief of Mamie Till-Mobley following the 1955 lynching of her son, Emmett Till, and the grief of Mary beholding Jesus on the cross.

Not wishing to profit from the death of Till, A Sanctified Art made Anderson’s images available to churches for free but encouraged those who used the work to financially support the Emmett Till Interpretive Center and The Innocence Project, something A Sanctified Art also did.

For her latest Lenten collaboration, Anderson used cotton applique to create “The Descent,” which examines Peter’s emotional journey as he’s confronted about his association with Jesus. Anderson said she channeled the faces of her Palestinian friends during the two months it took to finish the piece, so she designated two organizations that promote peace in the Middle East as her beneficiaries.

Anderson said she loves being invited to mesh her passions for art, ministry and justice. And though the women who run A Sanctified Art are white, they “take great care to create resources that are inclusive, particularly of those who have been ordinarily excluded,” she said.

“The conversations in these collaborations are really edifying and encouraging. There’s a lot of journeying together,” Anderson said. “I remain convinced that artists will be a huge part of our salvation, and I’m just grateful for partnerships like this helping us as well as we can to tell important stories and help communities understand things in new ways.

“When we find ourselves in turbulent times like these, it’s important we don’t fall back on old understandings that don’t go interrogated. And I think art helps us interrogate what we think we already know.”

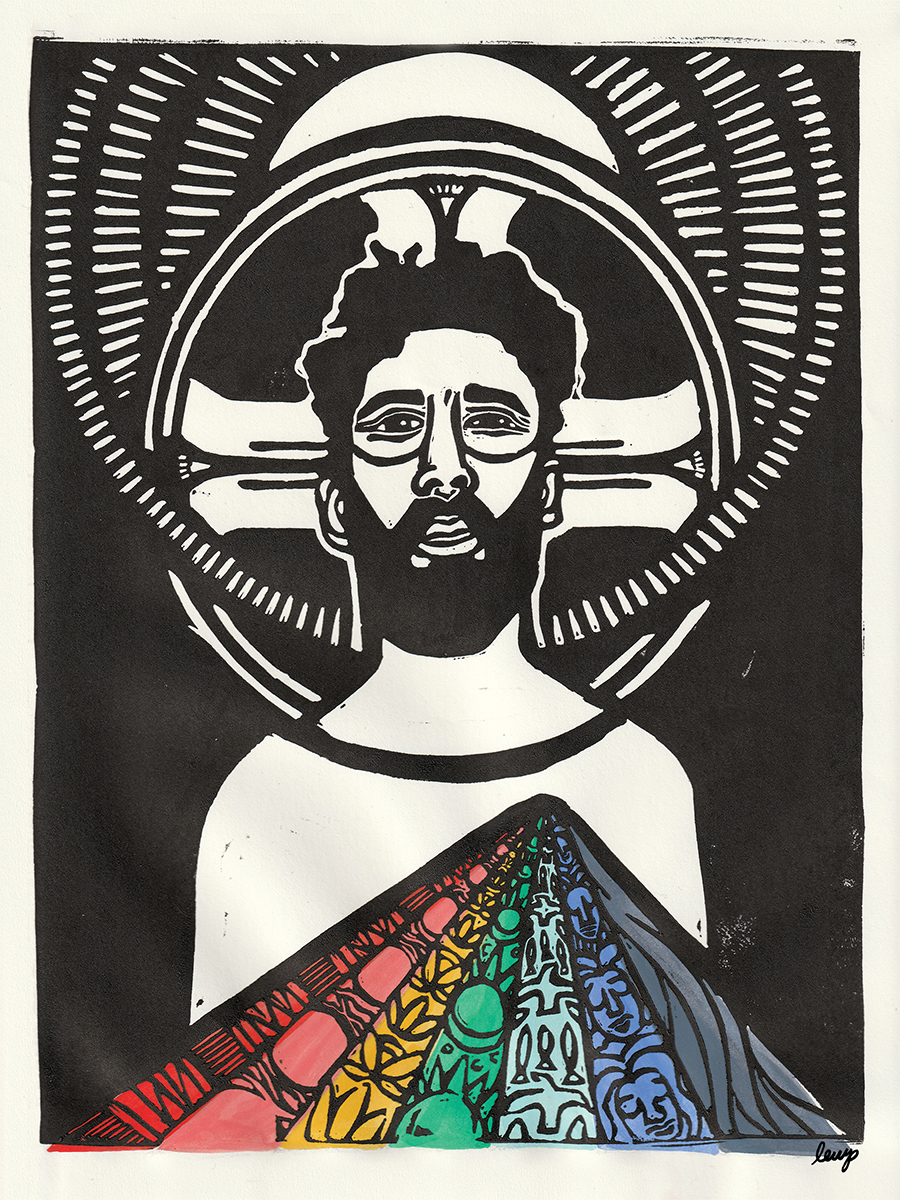

Promoting conversation, deeper connection

A Sanctified Art is candid about the oppression and violence perpetuated by the white church, which, it notes, used mass-marketed images of a white, blond-haired Jesus to bolster racism. In contrast, its staff is dedicated to pushing against outdated concepts of the image of God, challenging the whiteness inherent in classical images and the patriarchal language of religious texts.

How does your worship include those ordinarily excluded?

“I have for much of my life not found God in church,” said Hannah Garrity. “One of the reasons for that is the male language for God and the white male representation of Jesus, because we know by a vast scholarship at this point that those images have forwarded the antithesis of God’s call, in colonialism and oppression, by creating a hierarchy of race in divinity — and God’s just not in that.”

For the “Wandering Heart” Lent series, Hannah Garrity said that as she studied the Gospels, particularly the moment where Jesus predicts Peter’s betrayal and questions his loyalty, the voice she heard was that of a Black woman, checking a professed supporter’s commitment to the cause. She ultimately sketched two images of Peter and one of Jesus, representing each as a Black woman “to push back on the gender norms,” she said.

Meditating on the biblical text before picking up her paintbrushes is “the closest I come to prayer and a conversation with God,” said Hannah Garrity, who also serves as the director of Christian faith, life and arts at Second Presbyterian Church of Richmond, Virginia, and as a liturgical artist for the Summer Worship Series at Montreat. It’s important, she added, for viewers not to have a “static” experience when exploring her work but instead feel challenged to return to the Scriptures and seek their own meaning from the source.

The Rev. Doyle Burbank-Williams of New Visions United Methodist Church in Lincoln, Nebraska, said he appreciates that A Sanctified Art’s resources provoke questions, encourage reflection and leave room for individual interpretation.

“Part of the difficulty in our culture is we’re trained to want simple answers,” said Burbank-Williams, an artist himself. “We don’t entertain complexity very well, and my experience with A Sanctified Art is they don’t shy away from that complexity, the complexity of a loving God in a world that sometimes feels anything but loving. And that helps people find their pondering edges.”

New Visions is one of about a half dozen Lutheran, Presbyterian and Methodist churches in Lincoln using A Sanctified Art’s materials, and the group has engaged in some cross-denominational collaboration, said the Rev. Dr. Melodie A. Jones Pointon, the senior pastor and head of staff at Lincoln’s Eastridge Presbyterian Church. The churches don’t necessarily use all the resources in exactly the same way, but they brainstorm together and invite each other’s congregations to worship or engage in Bible study under one roof.

In what ways could you challenge worshippers to seek their own meaning from a source?

“We’re constantly examining what might be next, and loving exploring these interdenominational relationships,” said Jones Pointon. “We feel strongly that collaboration is the future. We’re stronger together than apart.”

That cooperation has extended into the greater community, with the churches jointly advocating for mental health resources, pretrial diversion efforts and affordable housing for residents in Lincoln, a culturally diverse city with a large refugee population. While most of her congregation is white, the youngest participants are largely people of color, many from South Sudan, and they appreciate being represented in A Sanctified Art’s visuals, said Jones Pointon.

“Our young people think visually; they think in Instagrams and Snapchats,” she said. “To see something coming out of the church community that only represents the people in the pews would be disingenuous. The kids and young people we work with would be like, ‘What is this?’ It’s not the world they live in.”

How does your church integrate visual imagery into worship?

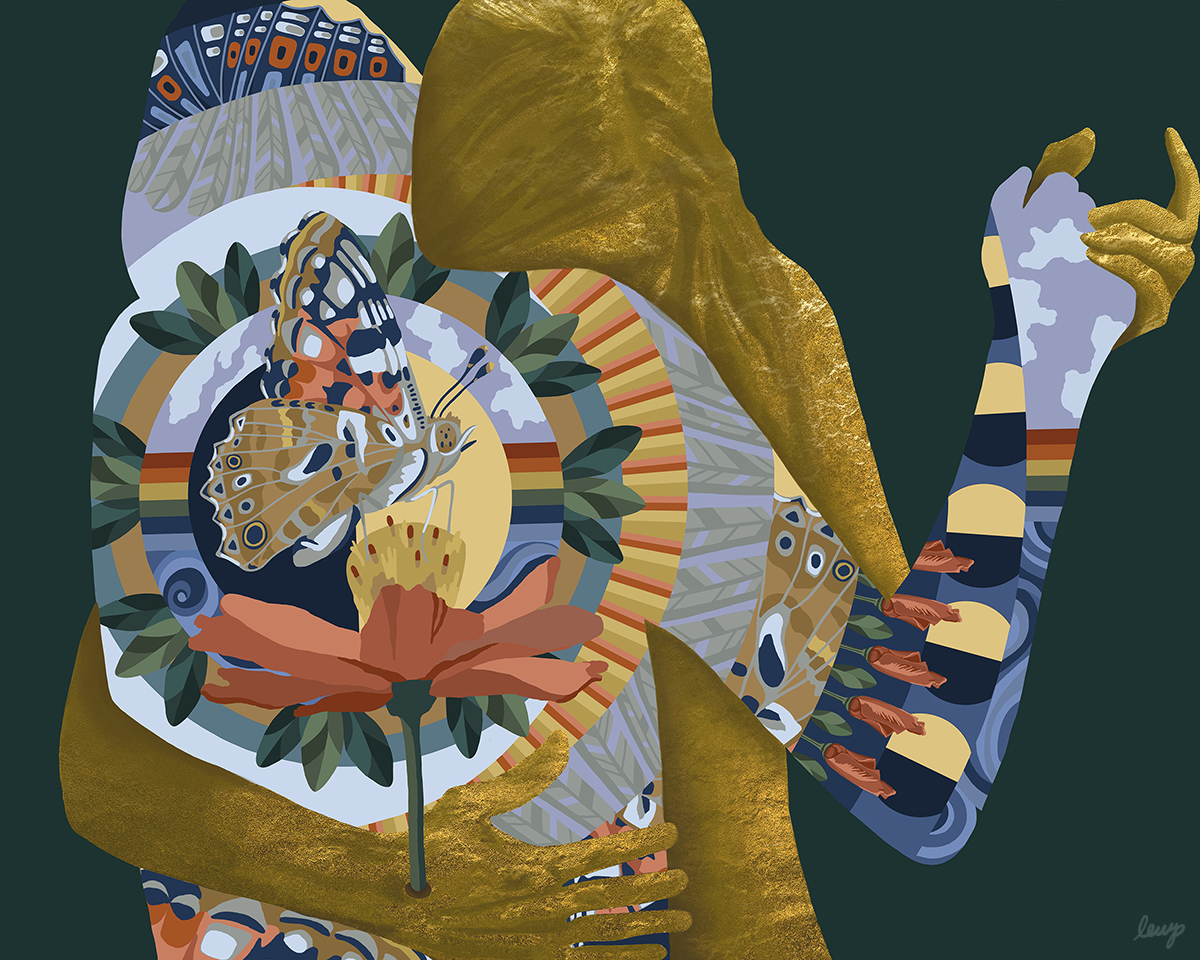

Lisle Garrity said she hopes that A Sanctified Art’s offerings affirm humanity’s diversity and expand the imaginations of those experiencing the work. Years ago, she led a worship service where she asked those present to examine a painting by Pittman titled “Anointed” and to imagine how God might be speaking to them through the piece.

The painting, which was inspired by the story of Mary washing Jesus’ feet, used brown skin tones for both. Garrity said an older white woman approached her after the service, saying she had initially failed to recognize Jesus’ foot because she hadn’t thought of him as having darker skin.

“I’m going to sit with that,” the woman told Garrity. “I’m going to be thinking about that for a long time.”

Garrity said hearing how congregations use resources helps A Sanctified Art understand the level of engagement and what materials have been the most meaningful. After eight years, the organization has a library of seasonal material, based largely on the Revised Common Lectionary. Because that doesn’t always share stories in sequential order, future resources may focus on providing more narrative cohesion to help people develop basic biblical literacy.

“What I really want is for people to see something new, see a story in a different way, see something they need to see,” Garrity said. “I want to see what art can do, see people get creative and be shaped by the creative process.”

Questions to consider

- How might church be a place where people discover what they are created to do?

- In what ways does your worship “widen access to God”?

- Does your community hold space for ideas you haven’t had yet?

- How does your worship include those ordinarily excluded?

- In what ways could you challenge worshippers to seek their own meaning from a source?

- How does your church integrate visual imagery into worship?