When I was young, Jesus greeted me every day at my grandmother’s house.

A framed print of Warner E. Sallman’s “Head of Christ” graced the wall adjacent to her front door. Jesus looked like an elegant surfer dude to me — tanned, with honey-streaked brown hair and blue eyes that gazed benevolently to the heavens.

The Almighty didn’t look anything like me, but so what? It certainly didn’t make me question my faith or my self-worth, because my religious experience was steeped in the tradition of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

From the all-Black choir that sang the songs of Zion to the Black mothers of the church who prayed over me to the Black pastor who preached that, yes, Jesus loved my little chocolate self, my Blackness was continually validated. At my grandmother’s, I was more concerned about her yelling at me for slamming the screen door than I was about the white Jesus hanging next to it.

But once I became aware of the world and my place in it, I realized that imagery was a powerful tool through which white supremacy operated. Whiteness has always been the default for defining everything America deems worthy: standards of beauty, true patriotism, innovators and intellectuals and stewards of power. Even our most sacrosanct attribute — spirituality — demands that we pray to a God presented as white.

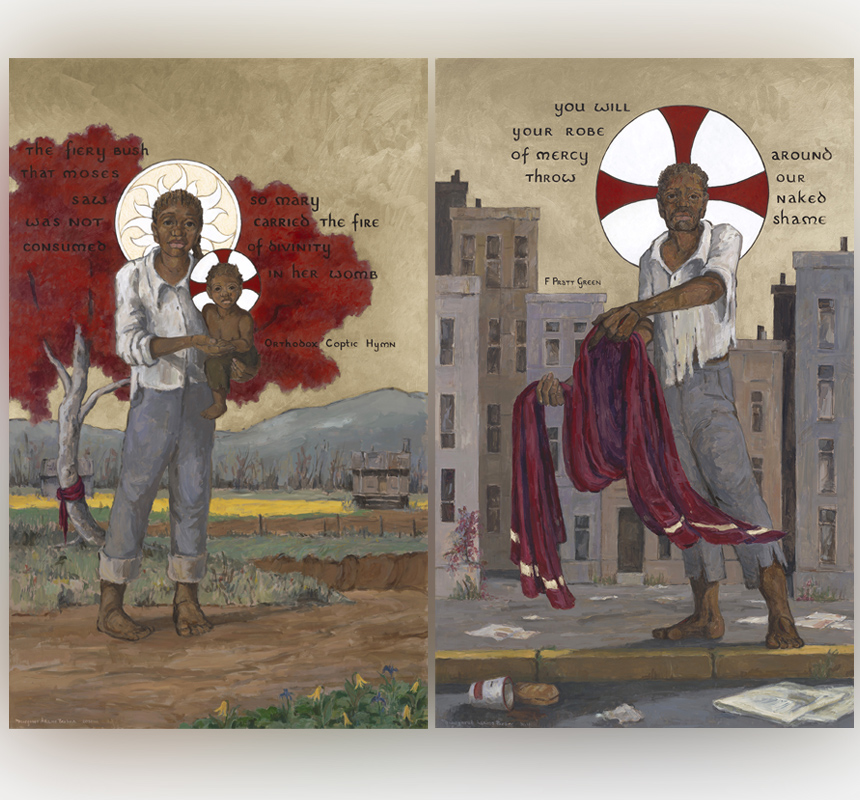

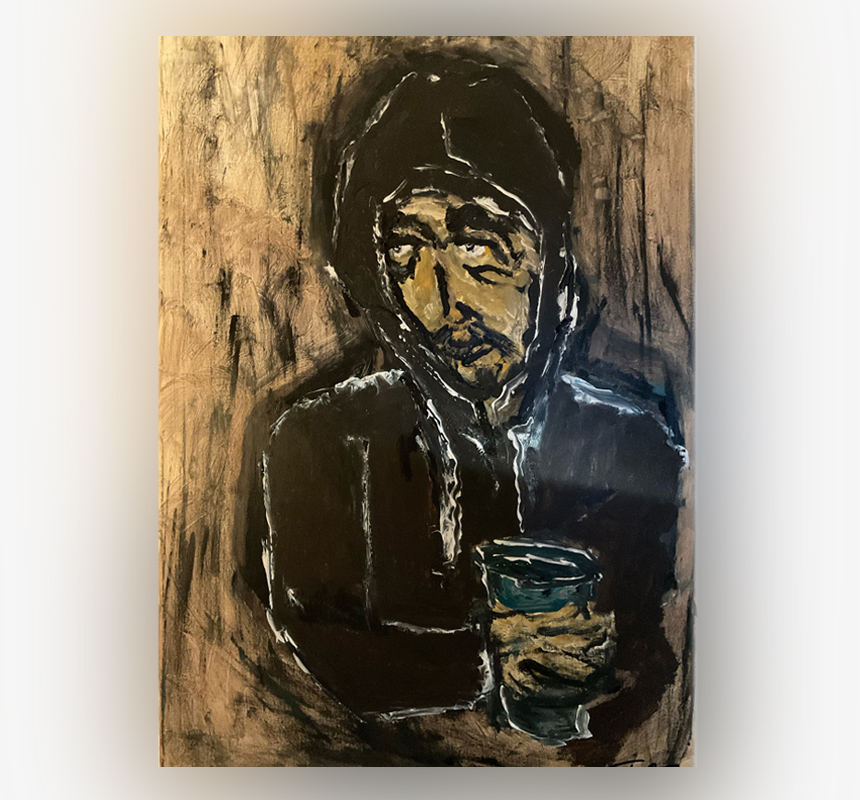

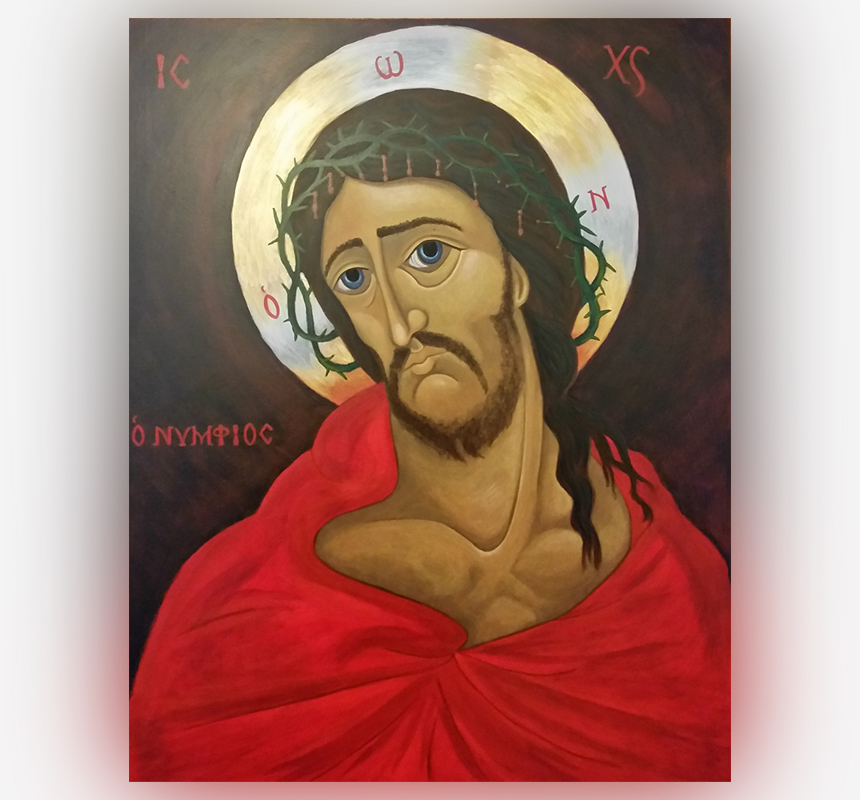

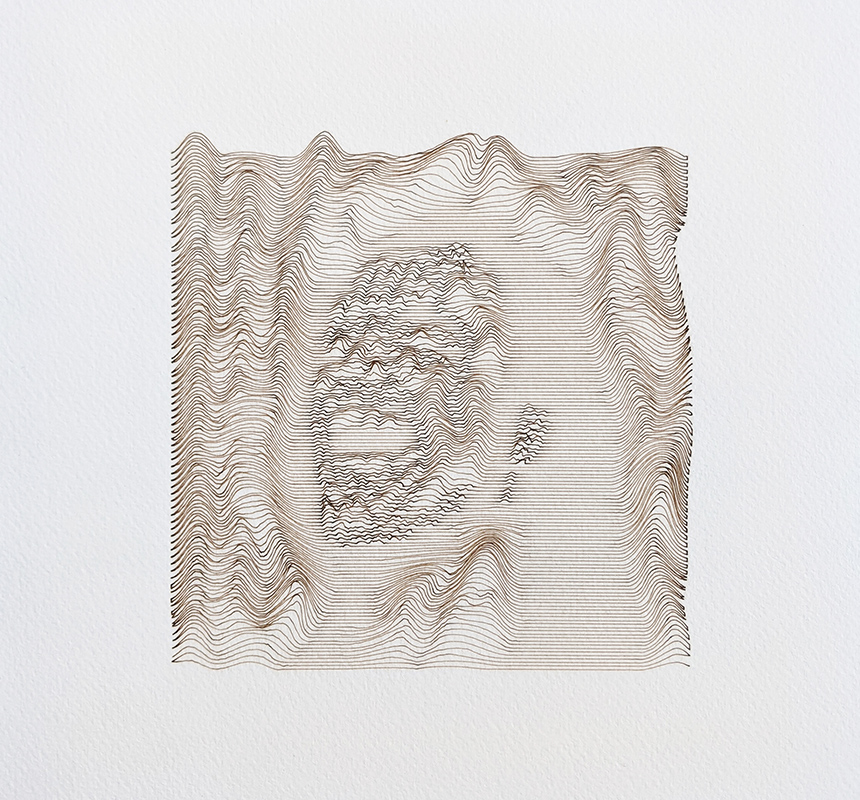

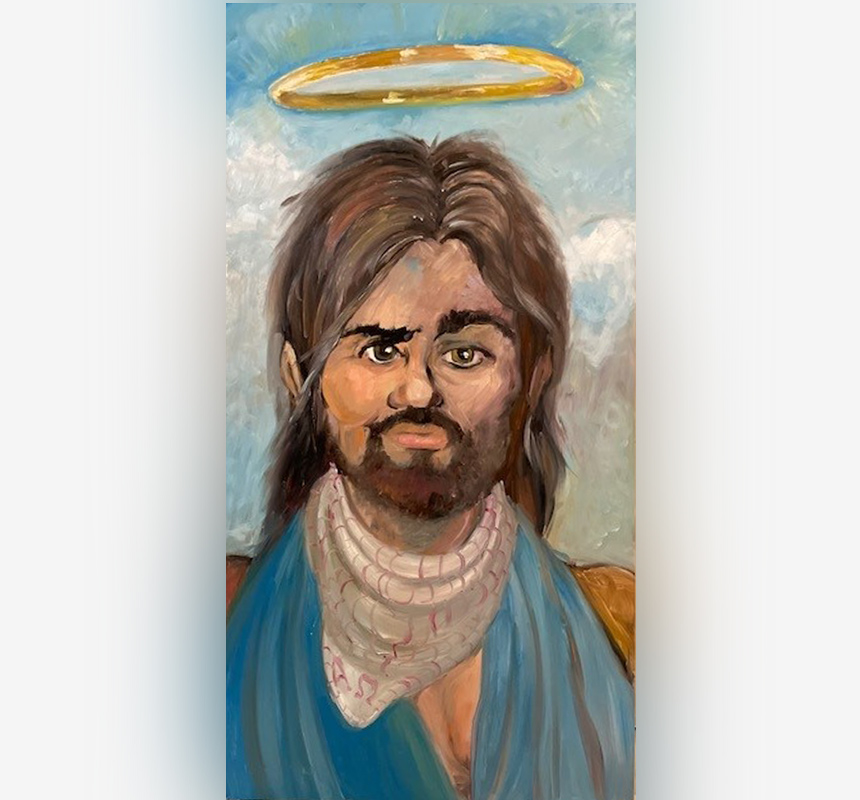

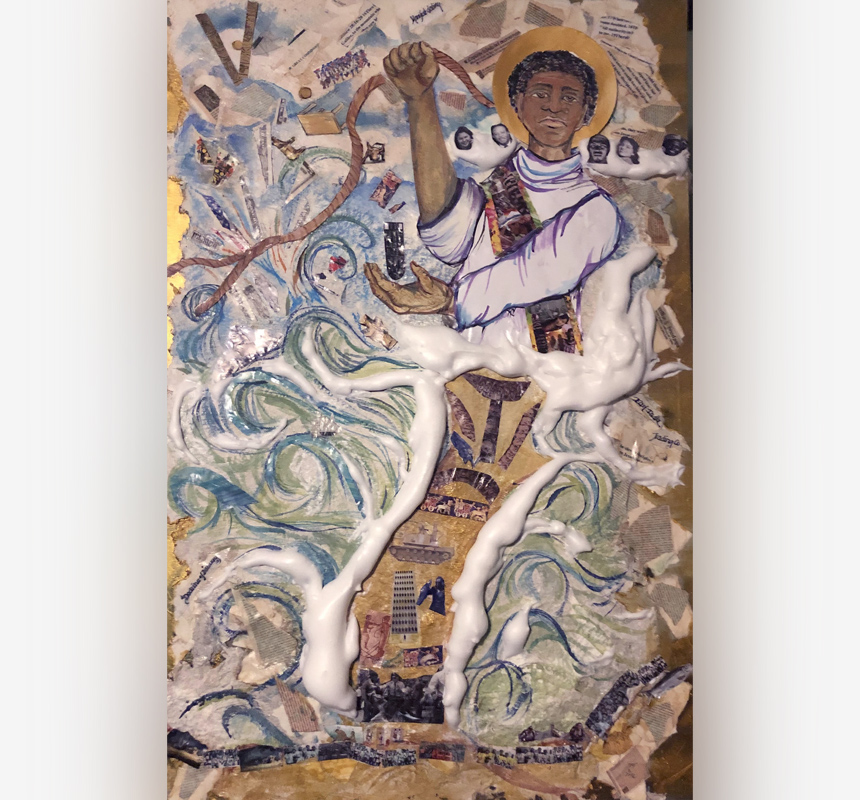

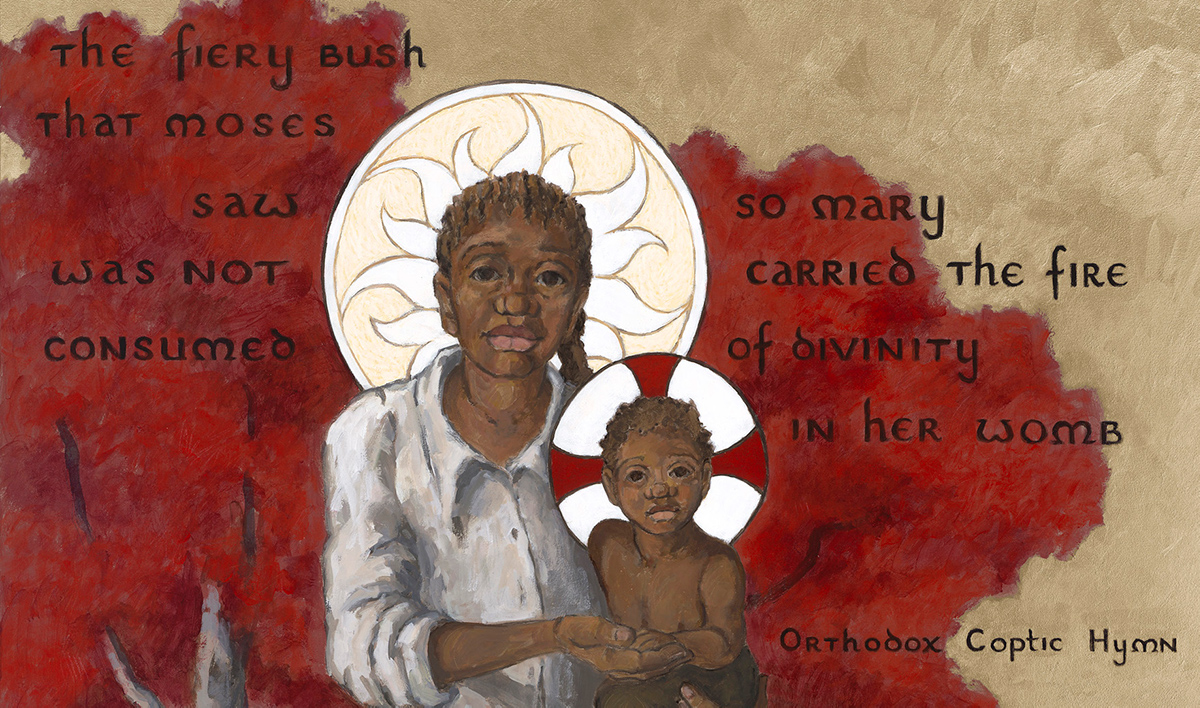

That’s why “DeColonizing Christ,” a visual arts exhibit that runs through Dec. 19 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, is so fascinating. It dares to imagine Jesus Christ as what he was, a person of color. It dares to debunk everything we’ve been programmed to believe about Christ’s appearance while interpreting a historical fact.

As the exhibit draws to a close well into the season of Advent, it has offered opportunities for those who have never deeply questioned their vision of Christ to reconsider the frame through which they have been looking.

What images of Jesus did you grow up with, and how do they align with your vision of Christ now?

Some of the exhibit’s artists took license to envision Christ as a woman, a Latino child, or a brother on the street sporting a halo-shaped afro and smoking a blunt. Each of the 40 pieces invites the viewer to imagine Christ as more provocative and edgy than the sanitized version we’re used to seeing.

“There are some people that will deny [that Christ was not white],” said Matt Parsley, of Harrisburg. “But I consider it to be a fact.”

On a recent Sunday, Parsley, who is white, viewed the exhibit with friends Helena Felix and Tracy Cisney. “In the long term, this exhibit could have an impact,” he said. “That’s the whole point of art, is to challenge your way of thinking.”

For the Very Rev. Dr. Amy D. Welin, the dean of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Cathedral, where the exhibit is displayed, it’s not a stretch to think of Christ as someone other than white and ethereal.

“Christ was edgy, and he hung around with edgy people,” Welin said. “We’ve so emasculated Christ that he’s like our pet gerbil. He’s not threatening — he’s nice. He’s the Good Shepherd. But we also see in the Bible that he’s kicking ass in the temple; he’s turning over tables. So he was good, but he wasn’t nice.”

We are in St. Stephen’s, strolling through the sanctuary, an immaculately reverent space that welcomed an average of 150 congregants every Sunday before COVID-19 hit. The images of “DeColonizing Christ” are juxtaposed with the stained-glass images of Bible characters, all depicted as white, that line either side of the cathedral. Taken together, the disparate images create an interesting theological debate.

“We all enculturate Jesus. Every tribe. We all paint him as one of us, which is fine, because we want to be close to God, and that’s what people do,” Welin said.

If any of these images challenges you, why do you think that is?

“But then we learn that the images of Jesus were used to silence and oppress people in Latin America and Indigenous people and the enslaved in the United States. So there’s this fine line that says we want Christ to be one of us … but we don’t want him to be one of you.”

The narrative of Jesus being “one of us” was normalized through commercialization of Sallman’s “Head of Christ” painting, the one that hung in my grandmother’s house. It has been described as the “best-known American artwork of the 20th century.”

Sallman, a religious painter and illustrator from Chicago, styled the painting to appeal to 1940s American Protestant audiences, and it was soon printed on prayer cards and circulated by all denominations, regardless of race. The image, which has been reprinted more than 1 billion times, defined the nation’s religious culture, creating another white default that most Christians took for granted.

“I always thought Christ looked like one of my people,” said Welin, a self-described pale-skinned Irish American. “I went to a Catholic high school, and the images we had in textbooks and religious art were of a Jesus who was definitely European.”

It wasn’t until she was well into her 30s that the revelation hit her: according to the Bible, Christ was a Palestinian Jew. Even as a medieval history major, Welin was never taught that. Years later, after Trayvon Martin was murdered, she started to consider how white supremacy manifests itself in ways big and small. It wasn’t lost on her that public outcry had forced the removal of certain public monuments and other symbols of the nation’s racist past. Meanwhile, every Sunday, the stained-glass images in her own church stared at her almost mockingly.

“It became really clear that the image of Christ had been commercialized and promulgated,” Welin said.

How could your congregation explore the enculturated history of Christianity as part of formation and worship?

Last year, a parishioner told Welin that if she really was serious about doing the work of diversity and inclusion, she need look no further than her own sanctuary. “Because all of the iconography in the cathedral says this is a white space,” he told her.

“And I was like, ‘Wow, we need to broaden our palette. This is an opportunity,’” the priest said.

Welin met with staffers at the Art Association of Harrisburg to brainstorm about the concept. One of them pointed out that it seemed the theme of the exhibition should be decolonizing the image of Christ.

“And that’s how we got our title,” Welin said.

She enlisted the Rev. Mack Granderson, the pastor of Crossroads Christian Ministries Church, also in Harrisburg, to chair the selection committee. A music major from Philadelphia who for years owned a jazz club in Harrisburg before going into ministry, Granderson was well-qualified to lead the project. In the ’80s, he served for seven years under then-Gov. Richard Thornburgh on the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts.

The committee reached out to artists, universities and arts organizations in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware and Washington, D.C. They secured a grant from the Arts for All partnership, a collaboration between the Cultural Enrichment Fund and the Greater Harrisburg Foundation.

In all, the show features 28 original artworks, plus a dozen on loan from private collections. Although the images are unquestionably thought-provoking and confront racism in diverse interpretations, there is a troubling omission. All but seven of the 17 participating artists are white, and two out of three cash prizes awarded in the juried exhibition went to white artists. Michael Reyes, a Franciscan friar and trained artist from the Philippines, won the People’s Choice award for his work “Christ the Dreamer.”

If some of the most-praised works in an exhibit that seeks to challenge white supremacy are created by white artists, and if lived experience is the biggest informer of personal expression, what does that mean for the exhibit?

It’s a question that gets to the heart of the complicated nature of racism, intended or not. The novelist Toni Morrison once noted that she worked hard to write without the intrusive “white gaze,” the idea that Black writers must explain cultural references to white readers, must hand-hold and make them feel comfortable.

How does the art in your church reflect your congregation’s beliefs?

Lori Sweet, of Harrisburg, award winner of the Bishops’ Prize for her work “The Healer,” admitted that she hesitated to enter a piece in the show because her previous religious works focused more on the feminine and nature. Portraying Christ as a person of color didn’t fall into her wheelhouse, in part because she is white.

“I did feel like, ‘Who am I to represent this, because this isn’t my experience,’” said Sweet, who has a background in social work. “But it’s been part of my life’s work to stand up and be present for people who are oppressed and suffering and bear witness to that. So I feel honored and grateful that I can stand in solidarity with others on this issue — and it’s continuing to inform me.”

“The Healer” features an olive-skinned, hooded-robed Jesus. He has a direct gaze and full lips, holding a lamb that represents “not a sacrifice but the true and authentic part of who we are, the delicate and vulnerable part,” Sweet said.

“I think when people look at each other, they’re seeing the outward appearance,” she said. “And I guess I see Christ as being able to look beyond the surface and being able to see the sacred in each of us, and that is healing.”

In your church’s context, what gaze is missing? How might it be valuable to include that perspective? How might you invite it in an authentic and respectful way?

Best in show went to “Pantocrator in Black and Brown” by Brian Behm of North Carolina.

For Granderson, who is Black, the lack of participants of color was disappointing, though understandable. His years serving on the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts taught him that recognition for artists of color, getting their works displayed in galleries and museums, has been an ongoing struggle.

“But then something came to mind,” Granderson said. “I was very excited for white artists, because they would have to go through something internally to create an image of Christ from Palestine. There will also be a reckoning that must take place with the person who is seeing the exhibit. I would hope that kind of conversation, even if it’s an internal conversation, must take place.”

Not surprisingly, countercultural images similar to those in the exhibit have drawn controversy. St. Louis artist Kelly Latimore’s “Mama,” depicting a Black Virgin Mary cradling Jesus’ body after his crucifixion — with Jesus portrayed as George Floyd — was recently discovered to be missing from a public exhibition of Catholic University of America’s Columbus Law School. Officials at the school replaced it with a smaller version.

Latimore, meanwhile, has faced death threats.

“I think, unfortunately, racism is part of a lot of it, especially death threats [that include] derogatory remarks about George Floyd specifically,” Latimore told Religion News Service, adding that some of the threats took issue with any depiction of Jesus as Black.

“Really white supremacist, racist stuff — which, theologically, is what racism is: a complete denial of the incarnation of Christ,” he said.

It may be that breaking down the barriers of systemic racism starts incrementally, with art exhibits like these. “DeColonizing Christ” not only dares to see Jesus differently but does so with none of the mean-spirited bickering that sullies our public discourse today. In their introspection, exhibitgoers may see themselves differently, too.

With that in mind, Welin is giving serious consideration to hosting rotating exhibits that feature different points of view at her church. “I really like the idea of using our cathedral as an art gallery, because then we could expand our spiritual life,” she said.

Harrisburg’s diversity — Pennsylvania’s capital city is 51% Black — demands that inclusivity be addressed. How to build community within the walls of the church is something Welin is still thinking about.

“This has been a local event,” she said. “It is wonderful that this has generated conversation in other churches about the use of art to illuminate matters of social justice. So perhaps the generative outcome is an opportunity to inspire other communities of faith to consider what they can do locally to address issues of justice. Because just like politics, justice is usually a local thing.”

As I sat in the sanctuary talking to Welin, it occurred to me that the exhibit was doing exactly what it was designed for — encouraging conversations that allow for expanding our worldview.

The God I know would be pleased.

“We can’t make up for 1,000 years of oppression,” Welin said, “but we can start to do things differently. And this is a start.”

How might different visions of Jesus broaden conversation in your church and community?

Questions to consider

- What images of Jesus did you grow up with, and how do they align with your vision of Christ now?

- If any of these images challenges you, why do you think that is?

- How could your congregation explore the enculturated history of Christianity as part of formation and worship?

- How does the art in your church reflect your congregation’s beliefs?

- In your church’s context, what gaze is missing? How might it be valuable to include that perspective? How might you invite it in an authentic and respectful way?

- How might different visions of Jesus broaden conversation in your church and community?