In 2012, as the church planned its 375th anniversary, members of Old Donation Episcopal Church looked for a way to tell the church’s story. They knew that people were attracted to the church because of its history. The old brick sanctuary, rebuilt on the foundations of the 18th-century building, was especially inviting, as were the historic headstones in the cemetery.

But as they looked for fun and fanciful stories to tell about the men and women who founded the church, initially known as Lynnhaven Parish, they stumbled on uncomfortable facts.

“We started realizing that some of these people we celebrated regularly also participated in some of the worst things that we could imagine, especially [in] the era of slavery, and it became more of a research project at that point to see what was really in our history,” said the Rev. Bob Randall, the former rector of Old Donation, who retired earlier this year.

That led to a decade of study, self-reflection and soul searching for the 800-member, mostly white congregation. Following the death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man killed May 25, 2020, by a Minneapolis police officer kneeling on his neck, just months after the killings of Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor, the church realized that there was more to do than research and lament its past. It also needed to make amends.

What are ways in which your church or ministry has explored its connections to racism in the U.S.?

The summer of 2020, also the peak of the coronavirus pandemic, was a time of racial reckoning across America and in many of its predominantly white churches.

Church committees drafted statements on the sin of racism. Members held silent vigils for the 9 minutes and 29 seconds that police officer Derek Chauvin pressed his knee on Floyd’s neck. Small groups read books such as “White Fragility” by Robin DiAngelo and “How to Be an Antiracist” by Ibram X. Kendi. Churches hung Black Lives Matter flags or banners. They invited Black pastors to speak from their pulpits.

But for many white churches that period of racial reckoning has ended.

“By the time we get to 2025, we have a number of different churches that had attempted to do programming and awareness building but had run into significant enough resistance and lack of clarity about what to do and a restlessness and frustration about what should happen next that a lot of those activities have significantly receded,” said Gerardo Marti, professor of sociology at Davidson College in Davidson, North Carolina, who studies the racial and ethnic dynamics of American congregations.

Polls bear out a loss of momentum. In September 2020, 52% of U.S. adults said the increased focus on issues of race and racial inequality would lead to changes that would improve the lives of Black people, according to a Pew Research analysis. By February 2025, 72% said the increased focus on race and racial inequality after Floyd’s killing did not lead to changes that improved the lives of Black people.

Some churches, however, have been able to keep their focus. And the last five years have transformed them. Old Donation is one.

What are ways in which support for racial justice has waned in your context?

Church members started investigating the church’s history in 2012, with a desire to find out more about a woman who in the early 1700s was tried in court for being a witch. Combing through parish records, including vestry or governing board minutes, church members discovered another woman, wholly unrelated, a slave by the name of Rachal.

Records from Oct. 14, 1767, read, “agreed and resolved by this vestry that the church wardens sell the Negro wench Rachal belonging to the Parish and that the money arising thereby be applied towards buying another Negro.”

That one detail set Daniel Ries, a retired Navy engineer and a member of Old Donation, on a journey toward racial justice.

“This woman who was an institutional slave was owned by the church,” Ries said. “That caught our attention.”

It turned out Rachal was far from the only slave owned by the church and its leadership. Several of the church’s pastors owned slaves. One of them, the Rev. Robert Dickson (1716-1777), requested in his will that at least five of his slaves be sold to the church upon the death of his wife and that the proceeds be used to establish a school for orphaned white boys to be called the Dickson Free School. That donation ultimately led to the renaming of the church as Old Donation.

Your ministry may not be 375 years old, but do you have a records keeper or historian who documents your institution’s memory?

By the spring of 2020, as Americans began confronting the reality of police brutality, the church went deeper. That summer, it began offering an antiracism curriculum for small-group discussions developed by the Episcopal Church called Sacred Ground. The church ran eight Sacred Ground small groups, each meeting 11 times for about two hours. About 80 people, or 10% of Old Donation members, participated.

“Our goal was to talk about the truth of our history and to get people to realize what William Faulkner said: ‘The past is never dead. It isn’t even past,’” Ries said.

One outcome from the Sacred Ground curriculum was the formation of the Becoming Beloved Community Commission. That committee was largely created to make amends.

The church established an endowed scholarship in honor of Rachal at Norfolk State University, Virginia’s largest historically Black university. It partnered with the Urban Renewal Center in Norfolk, a nonprofit that provides support services to underserved communities.

Each Tuesday, church volunteers drove children from Virginia Beach low-income public housing to a Norfolk church for a special program that also feeds them. Church members with experience in engineering, like Ries, organized a special STEM-themed summer camp for children from disadvantaged families. Church volunteers helped move formerly homeless people into more stable housing. Ries bought a pickup so they wouldn’t have to rent moving trucks.

“They’ve really been doing everything they can with the resources that they have — human resources, facility resources, assets — so the work we do can have a shared success,” said Antipas Harris, president and CEO of the Urban Renewal Center.

Members of Old Donation have also cultivated a relationship with Morning Star Baptist, one of oldest African American churches in Virginia Beach. Some of the men from Old Donation are regulars now at a men’s breakfast that Morning Star hosts.

When Old Donation decided to take action, the denomination provided support and resources. What sorts of support and resources are helpful to your ministry in education and action?

They have also befriended Morning Star historian Joyce Venning. When she told them she had been entrusted with the church’s oral history, they encouraged her to come to Old Donation so they could video her telling the story of how seven families, most of them sharecroppers, began worshipping and eventually built a Black church. It’s a history, she said, that the city of Virginia Beach has not fully recognized.

“Old Donation Episcopal Church has embraced me and encouraged me to continue on and to do what needs to be done to bridge this gap and to truly live out the meaning of Galatians … that we are truly all God’s children,” says Venning, 79, at the end of the video.

During a recent Black History Month, Old Donation invited Morning Star members to a fellowship meal and a viewing of the video they had produced.

Such commitment to the work of repair is the exception to the rule, say sociologists who have studied how white churches are responding to racial justice.

Other church pastors said the work of racial justice takes intention and focus.

It is increasingly difficult to talk about or take actions for racial justice. What are some ways in which your community has responded?

Chris Furr, a pastor of Covenant Christian Church in Cary, North Carolina, a Disciples of Christ congregation, said the reelection of Donald Trump and the growing political polarization has made it harder to focus.

“Churches like ours feel very inundated,” Furr said. “There’s so many justice-oriented issues, so many populations that feel targeted. It can be overwhelming for the church to discern its priorities in ways that are meaningful, because it does feel a little bit like there’s this avalanche of things folks feel we need to react to and respond to.”

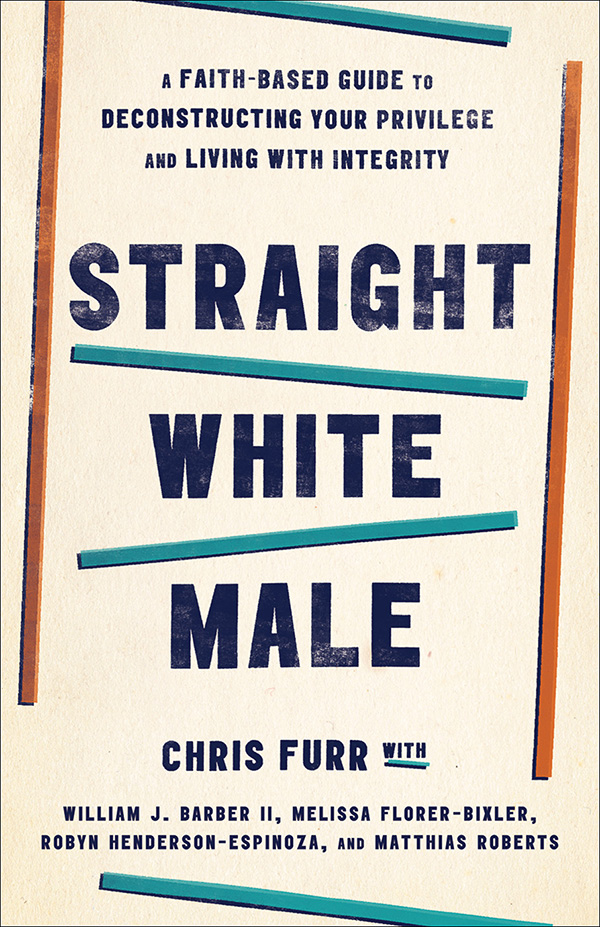

Furr, who has always felt called to the work of racial justice and in 2022 wrote “Straight White Male,” a book about deconstructing privilege, is also trying to steer the church toward more truth telling about the larger Raleigh story of race.

In evangelical churches, it may be harder.

Bobby Warrenburg, senior pastor of North Shore Community Baptist Church, a congregation of 600 members in Beverly, Massachusetts, said the murder of George Floyd demanded a response.

The church was not meeting in person because of COVID-19, so Warrenburg, who is white, and two pastoral colleagues, one Asian American and the other Black, got together to produce a video statement that talked about racism as a violation of God’s will and intention for humanity. Later, the church read Jemar Tisby’s 2019 book, “The Color of Compromise: The Truth About the American Church’s Complicity in Racism.”

But Warrenburg said there are obstacles to continuing the conversation. One big one, he said, is the racial composition of the Boston suburb where the church is located. It’s 87% white, according to the U.S. Census, and less than 3% Black.

“You have a lot of suburban white churches that are very aware,” Warrenburg said. “Their eyes have been opened, they’ve awoken to their theology, they’ve awoken to their Scripture, they’ve awoken to their history — and that’s good. But … that relationship aspect is just still a real gap.”

Old Donation Church has done a lot of work on addressing its history, but more than a decade after it began its racial reckoning, members say there’s still much to be done.

The church is now wrestling with a handful of plaques and markers honoring prominent members of the church who also owned slaves. Opinion is divided on whether the markers should be taken down or whether the church should add some context for them.

“There are a lot of people that would rip it down, and I would be OK with that, but we want to make sure people know the real history,” Ries said.

This past April, Ries presented a paper at Oxford University about the church’s efforts to tell the truth about its history. He concluded: “Old Donation is still here after almost four hundred years. My hope and prayer [is] that the Old Donation Community will become a New Donation to social justice and become repairers of the breach, restorers of streets to live in.”

What are ways to catalyze awareness of racism without violent events?

Questions to consider

- What are ways in which your church or ministry has explored its connections to racism in the U.S.?

- What are ways in which support for racial justice has waned in your context? If efforts have not waned, what do you think has contributed to this ongoing support?

- Your ministry may not be 375 years old, but do you have a records keeper or historian who documents your institution’s memory?

- When Old Donation decided to take action, the denomination provided support and resources. What sorts of support and resources are helpful to your ministry in education and action?

- It is increasingly difficult to talk about or take actions for racial justice. What are some ways in which your community has responded?

- In your context, has awareness of racism come about when there is violence or death involved, such as the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery? What are other ways to catalyze awareness about racism without violent events?