Preserved in old vestry minutes, newspaper articles, correspondence and member rolls is a history some churches are beginning to grapple with -- the ways they have benefited from the labor of enslaved people, their championing of segregation from the pulpit or their tacit acceptance of systemic oppression under Jim Crow.

For faith communities that have begun admitting their transgressions, repenting of their role in America’s original sin can take many forms as they seek to heal wounds sometimes hundreds of years in the making.

This kind of racial justice work needs to be a top priority for churches, said the Rev. Joseph Thompson, the director of Multicultural Ministries and an assistant professor of race and ethnicity studies at Virginia Theological Seminary.

“We live in a society that has been thoroughly distorted by the many lies that our highly racialized social system perpetuates. As communities seeking to follow the way, the truth, and the life, it behooves us to challenge those distortions in word and deed, as we see them in ourselves and others,” he said in an email.

“How can we have the fullness of life to which Jesus calls us if we live unthinkingly surrounded by the lies of race and by the misguided personal behaviors and social structures to which those lies give rise?”

Faith leaders engaged in these efforts counsel that there’s no quick fix for what one deacon called “400 years of tears,” so congregations should be prepared to do steady, long-term work. Building trust where little exists requires radical truth telling and meaningful atonement, Thompson said.

Whose voices or stories does your congregation or organization need to hear for a more complete account of your shared past? How have you prepared members for those conversations, including the most troubling elements?

“At the organizational level, white institutions’ ‘owning’ and atoning for racist history is actually a step towards a more important goal -- fostering an institution that African Americans will genuinely want to claim because it is based in truth, justice and equity,” he said.

From the spiritual to the cosmetic to the corporeal, these are the stories of three faith communities in the midst of this work.

‘Listen with urgency’

Philip. Mingo. Flora. Rose.

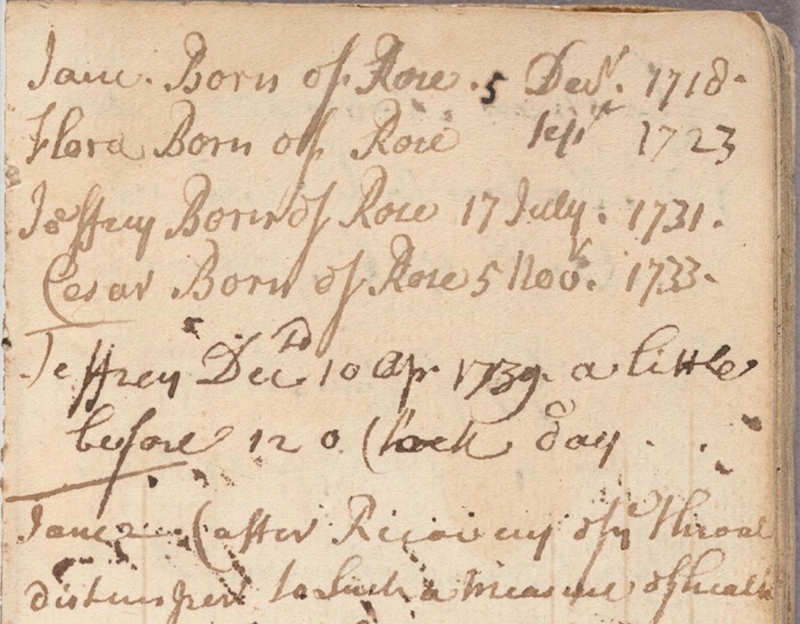

Listed euphemistically as “servants” of church families and clergy -- and often mentioned in baptism records only by their first names -- they are among three dozen enslaved Africans and Native Americans admitted to First Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts, during the 17th and 18th centuries. Their existence as second-class members was a painful discovery for the New England congregation, which dates back to the 1630s.

Digging through old church records housed at nearby Harvard University, member David Kidder said he uncovered the names while doing research for the church’s 375th anniversary in 2011.

“I have to confess, I came into this with a great deal of ignorance about slavery in the North,” Kidder said. “It was an education for me, as well as for the rest of the congregation.”

The congregation had embraced the United Church of Christ’s call for sacred conversations around race years earlier, sponsoring speakers, a film series and book groups, hosting multicultural services, and leaning into their vision of a Beloved Community.

But the church’s direct connection to slavery as signified by that list of names compelled the congregation to move beyond the programmatic, said member Peggy Stevens. While racial justice conversations continued, members also lobbied for criminal justice reform, rallied with Black Lives Matter and made pilgrimages to Southern sites associated with the civil rights movement.

“We called them pilgrimages because with a pilgrimage, you’re open to change and new awareness and reflections and not just ‘OK, check, I went to Selma.’ We started having experiences where we’re bringing it to people’s hearts,” she said. “It’s not, ‘Let’s feel bad about it.’ It’s, ‘How do we personally and as a congregation do reparations? What does it look like, this church we want to become?’”

On sabbatical in early 2018, the Rev. Dan Smith, the church’s senior minister, visited Montgomery, Alabama; Berlin, Germany; and Auschwitz, near Krakow, Poland, in an effort to understand how communities face their traumatic pasts. By 2019, the congregation felt ready to move from memory to action in the broader community and prepared to issue a request for proposals to artists and designers of color, seeking guidance on ways to share the stories of its enslaved members while promoting healing and repair.

A Black member of the congregation with a background in justice and equity work urged them to pause. While the church had engaged a small group of well-established leaders of color to be accountability partners, she said it also needed to consult with and follow the lead of others who had been most harmed by slavery’s legacy: the homeless, formerly incarcerated individuals, working families, Black teachers and teens.

What resources have you identified to explore your history? Who can support you?

In their urgency to heal their own spirits, First Church’s members had skipped an important step, recalled Smith, who said he remains “grateful for the body check.” Since then, they’ve sponsored focus groups, paying participants for their time, to help evaluate the community’s needs and engage in frank conversations that would have been impossible without that relationship building, Smith said.

“There’s got to be a relinquishment of the agenda that goes along with that urgency. It can’t be about us or our connections,” he said. “I think we’ve got to learn how to listen with urgency, follow Black communities with urgency and shut up with urgency.”

Humility is key, said Smith, who resists speaking to the press, because he considers the work a “moral imperative,” not something to boast about. He’s encouraged to see “people’s hearts and minds transformed.” Initially, 20 to 25 parishioners showed up to racial justice events; attendance is nearly four times that now. Still, after a decade of work, there’s much left to do. “It feels like we’re just getting started,” Smith said.

It’s incumbent upon faith communities to engage in this work, particularly since early theological rationalizations for slavery “helped to shape, promote and undergird the systems and structures of white supremacy,” he said.

“It feels like a moment where white people are starting to recognize huge gaps in their education, and it’s exciting to be able to hear these voices. If we really believe the truth will set us free, then there’s a profound opportunity to do the work of truth telling and see where it leads us.”

‘They’re not ready to be erased’

At St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia, the nameplates that marked the pews where Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee worshipped during the Civil War are gone. So are the memorial plaques honoring Confederate soldiers and the images of the Confederate battle flag once embroidered into kneelers near the altar.

Meanwhile, a different kind of tribute has sprung up on the steps leading to the columned front entrance of what was once called the Cathedral of the Confederacy. In May, as residents marched through the former Confederate capital demonstrating for police reform and racial justice, protestors spray-painted the steps with the phrase “I can’t breathe,” along with the names of Black people who had died in police custody. Sandra Bland. Breonna Taylor. George Floyd. Since then, mourners have left flowers next to each name.

The church scrubbed away any obscenities protestors left behind, said the Rev. Charles Dupree, St. Paul’s rector. But the names and Floyd’s last words as he suffocated beneath the knee of a Minneapolis police officer will remain indefinitely, he said.

“It’s grounded in the idea that these names aren’t graffiti. ‘Graffiti’ comes from the word to scratch or scribble,” Dupree said. “They feel to me more like memorials, almost as if a psalmist had written them: ‘How long, O Lord, how long?’ The names of these people on the steps of our church are confronting us, and they’re not ready to be erased.”

Most of the church’s Confederate iconography was removed in 2015 as part of its History and Reconciliation Initiative, a movement sparked after a white supremacist murdered nine Black churchgoers at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. In prayerful conversations facilitated by an outside consultant, members of predominantly white St. Paul’s acknowledged that the images failed to match the church’s contemporary dedication to social justice.

Since then, several HRI committees have examined the impact of the church’s racial history on its music and liturgy as well. Chris Graham, the chair of the historical research group and a historian at Richmond’s American Civil War Museum, wrote a book about some of the committee’s findings. “Blind Spots: Race and Identity in a Southern Church” has been distributed among the congregation in anticipation of a churchwide discussion in October, Dupree said.

Looking outward, St. Paul’s intends to use its resources to mentor youth, advocate for health care and affordable housing, and otherwise help marginalized populations, said vestry member Victoria Howell. Cognizant of the harm done by the “white savior complex,” Howell said St. Paul’s wants to see “where we can maybe not be the only voice but find a way to be helpful to the voices that are already in the community, especially the Black and brown voices, where we can lend the resources we’re so blessed to be able to have and amplify the work already being done.”

What amends does your congregation or institution need to make in order to move closer to a vision of Beloved Community? What could be your next step in that work?

Dupree noted that he was drawn to the 175-year-old church in August 2019 in large part because of its commitment to self-examination. A practitioner of mindfulness and meditation, Dupree said churches benefit from that same willingness “to look honestly at themselves and their past.” He added that white faith leaders like himself can set an example for their congregations by embracing the vulnerability necessary to face their own flaws.

“I’m not always right. I don’t have all the answers, and I’m going to step in it sometimes. It’s important for others to see it,” Dupree said. “We become so paralyzed that we’re going to do something wrong and look foolish or inferior, and that keeps us from doing anything.”

While the removal of plaques and artwork can literally happen overnight, Dupree cautioned that true social change takes a deeper, long-term commitment. That means providing lots of opportunities for parishioners to examine not just the church’s history but their own, he said.

“It’s not only about performative allyship. You have to change hearts and head spaces, and that’s a slower lift, unfortunately. Our sisters and brothers of color -- they’re tired of waiting around.”

‘Be ready to deal with it’

When the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland challenged its parishes in 2012 to explore their racial history, it wasn’t a rhetorical exercise. Some of the state’s earliest Episcopal churches were built by enslaved people or with money generated by slave labor. After the Civil War, the diocese established separate congregations and seminaries for Blacks. Predominantly white churches that accepted the diocese’s challenge were almost certain to uncover shameful histories.

As a leader, how will you respond to constituents who oppose rigorous self-examination?

“Something is going to fall out of the bushes, somehow, someway,” said the Rev. Christine McCloud, the diocesan canon for mission. “This is a conversation that can make grown men run from the room screaming and crying, … so you have to be ready to deal with it.”

About two dozen congregations have participated, publicly owning their histories around slavery and segregation and pledging to make amends for the damage they’ve done. These congregations are now stations along the Trail of Souls, essentially a map of the church’s transgressions against the Black community.

In recent years, the diocese has invited the faithful on “an ever-expanding pilgrimage toward truth and reconciliation” by posting a virtual tour and guide on its website, sponsoring prayerful in-person visits to stations along the trail and urging congregations to use what they’ve learned to transform their communities.

“In order to bring people to wholeness, to fullness, for us as a church to live into God’s promise, we can’t just continue to close our eyes to the history of the church,” McCloud said. “We know the work isn’t done.”

The process has been revelatory, even for some of the more enlightened congregations. Over the last 50 years, Memorial Episcopal Church in Baltimore, founded in 1860, had built a reputation as a progressive urban church, backing the anti-war movement, sponsoring social justice missions, and being the first church in Maryland to call a female priest and an openly LGBT priest.

But a deep dive into its archives uncovered disturbing findings, said the Rev. Grey Maggiano, the church’s rector since 2016. In the 1950s, rather than integrating a youth center that the church operated with a nearby Presbyterian congregation, Memorial had allowed the center to shut down and then dismissed the rector for fear that his outreach to poor residents might lead to integration in its pews, Maggiano said.

Records showed that the church, a haven for Confederate veterans and displaced Southerners after the Civil War, had hosted minstrel shows in the early 20th century and supported efforts to keep Black people out of the surrounding neighborhood, he said. The church’s first rector, the Rev. Charles Ridgley Howard, was a slave owner. And the parish had been built in memory of Henry Van Dyke Johns, an Episcopal clergyman and slave owner whose brother served as the chaplain to Robert E. Lee. Plaques to both ministers hung in the church’s sanctuary.

The truth about the church’s past was painful, but it became personal after Deacon Natalie Conway arrived in 2018. Soon after, genealogical research by Conway’s brother revealed that their ancestors had been enslaved at nearby Hampton plantation -- an estate once owned by the family of founding rector Howard, whose plaque held a place of honor where she now preached.

“At that time, I was sitting in church and looked up at his plaque. I was like, ‘What am I doing here? I’ve got to get out of here,’” said Conway, whose brother talked her into staying. “He said, ‘No. You’ve got to tell this story.’ I said, ‘I’m going to have to pray about this.’ You read these things, but until it hits you personally, you don’t really know how you’re going to react.”

If your congregation or institution is predominantly white, how can you avoid further burdening persons of color as you engage with these questions?

Conway said she shared her family’s painful history with the congregation, and together, through prayer services and events, the congregation examined its record on race and pledged to atone. In August 2019, more than 50 members of Memorial and nearby Church of St. Katherine of Alexandria, a predominantly African American church, visited the Hampton plantation, now a national historic site.

After touring the spacious mansion and cramped slave quarters, the group held a libation service, offering prayers and pouring holy water onto the ground. Conway and parishioner Steve Howard, who is a descendant of Charles Ridgely Howard and a longtime friend of Conway’s, concluded the service by pouring water together in an act of healing.

Because the church historically caused “substantial harm” to Baltimore’s Black community by supporting segregated housing and aggressive policing and by failing to serve its youth, Memorial has more recently, as intentional acts of reconciliation, joined community efforts to support low-income housing, bail reform and schools, Maggiano said.

How would your congregation or organization define racial reconciliation? How might persons from different backgrounds define it?

The parish is removing the plaques honoring Howard and Johns, which will be laid in Memorial’s garden with contextual signs. He said Memorial is also commissioning a new painting to replace an 18-by-12-foot canvas featuring “an extremely white Jesus,” created as a memorial to a segregationist rector.

Conway said her initial anxiety about sharing her family’s story has given way to hope for meaningful change.

“It took a lot for me to tell this story, not knowing how people were going to react,” she said. “But the congregation has been so open, caring and loving. Opening up about my story I hope will allow others to do the same.”

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- Whose voices or stories does your congregation or organization need to hear for a more complete account of your shared past? How have you prepared members for those conversations, including the most troubling elements?

- What resources have you identified to explore your history? Who can support you?

- What amends does your congregation or institution need to make in order to move closer to a vision of Beloved Community? What could be your next step in that work?

- As a leader, how will you respond to constituents who oppose rigorous self-examination?

- If your congregation or institution is predominantly white, how can you avoid further burdening persons of color as you engage with these questions?

- How would your congregation or organization define racial reconciliation? How might persons from different backgrounds define it?