America has always been a place pulled in opposing directions, a country steeped in contradictions. It was born as a refuge for dissenters looking for freedom, even as those dissenters set about spurring its growth by enslaving others.

It built its independence on secular “self-evident” truths, yet even today, it often tries to beat those back with evangelical beliefs. It is a nation formed by immigrants who pushed out and punished the natives like interlopers and then became pointedly exclusionary, deciding who could be a citizen, who was a real American.

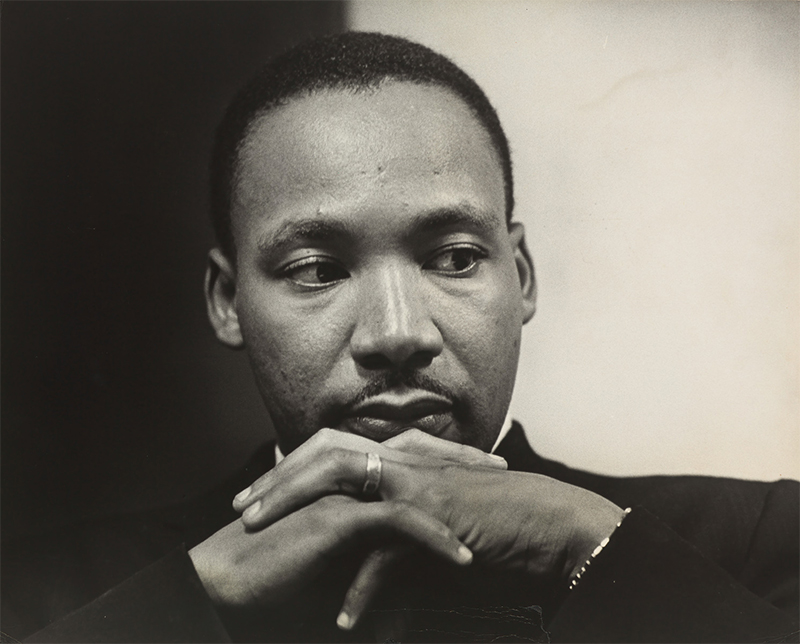

That’s why the convergence of Donald Trump’s second inauguration and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s annual holiday makes a curious kind of sense. These are two deeply American men, forged by America’s divisions. As King once said, “We are not makers of history. We are made by history.”

Think of Jan. 20, 2025, as a spiritual eclipse of America’s messy souls.

Trump often proclaims his desire to make America great again. While he can be vague about the specifics of how he plans to achieve that or what previously made the country “great,” he characterizes the nation as currently in decline and in need of revitalization. Control is a central theme; he sees a government with too much bureaucracy, one that’s been allowed to run amok with regulation.

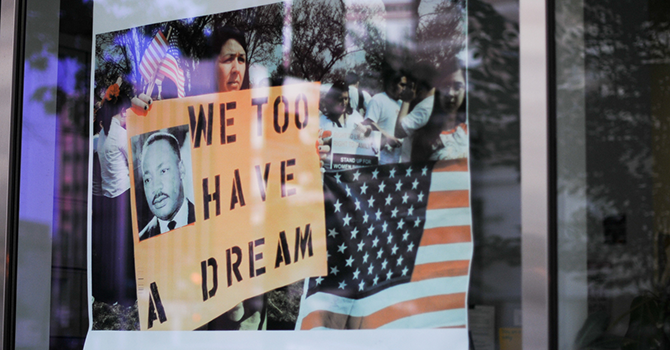

King saw an America that wasn’t living up to the promises codified in its foundational documents; it could be great, he said, once it found its moral center and let go of its three evils — racism, excessive materialism and militarism. King often spoke of freedom in the context of political and legal rights, not just personal autonomy. In that way, he was referencing liberty as it was named in the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Trump seems to believe America can succeed by returning to a past he’s known. King believed the country could succeed despite its past, by repenting of the sin of slavery and then, through reconciliation, creating a beloved community centered on the people.

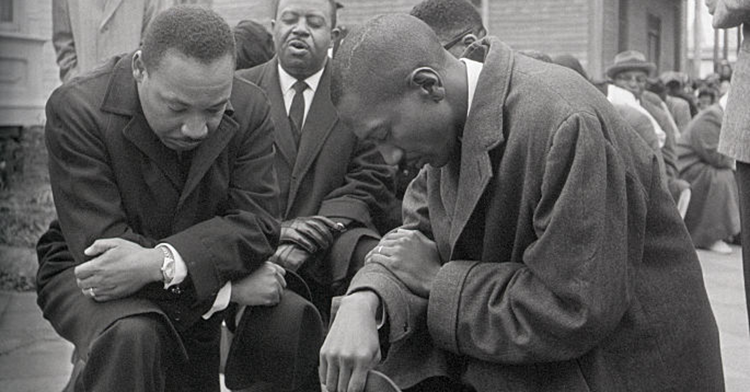

As an ordained American Baptist minister, King led a movement grounded in Christian theology. His organizing was done in the church. His message relied on biblical principles of love and forgiveness. He saw slavery and racial segregation as a “tragic blindness,” noting the humanity of segregationists even as he questioned their beliefs.

“They go on blindly believing in the eternal validity of an evil called segregation and the timeless truth of a myth called white supremacy. What a tragedy! Millions of Negroes have been crucified by conscientious blindness. Like Jesus on the Cross, we must look lovingly at our oppressors and say: ‘Father forgive them, for they know not what they do.’”

Trump leads a movement too, but one rooted in nativism, populism and xenophobia and adopted by white Christian nationalists who believe God has called them to have dominion over American society. Trump’s words about forgiveness on CNN land differently: “Why do I have to repent or ask for forgiveness if I am not making mistakes? I work hard; I’m an honorable person.”

Think of Jan. 20, 2025, as a spiritual eclipse of America’s messy souls.

The divergence between the two men — those perspectives on American history — is the hump we collectively can’t seem to get over. Some of us look at the past as a period, in both senses of that word. The past, some believe, happened and ended, and now we’re on to something new. Others see the past as a comma, if you will. It’s a part of a whole that connects and affects what was before and what’s after.

King once said that one of the great things about the U.S. was the right to protest, and he did so fervently, effectively and nonviolently. Yet honoring an activist who challenged the country’s morality has always been an uneasy fit in America’s list of holiday commemorations. It feels especially awkward now, when we’re regaining a president who has described peaceful protestors as “terrorists,” had them dispersed with rubber bullets, and threatened to use the military against them. In another note of cognitive dissonance, we might witness on this King Day a presidential pardon for some of those convicted for violently attacking the United States Capitol and the police officers charged with its protection.

It took 15 years for the King holiday to be established and 17 more for it to be celebrated in every state. It’s now become “acceptable” enough that there are sales over the long weekend. King, once considered a threat and labeled a communist, now gets quoted by those whose only relationship to his message is that their life’s work is diametrically opposed to it. They make sport of twisting King’s words from saying that the color of our skin shouldn’t matter to suggesting that it doesn’t matter.

That kind of distortion is among the reasons the day feels precious and worthy of protection. In the spirit of its namesake, it’s not just a day off; it’s meant to be a day of service, of action. An inauguration typically marks the beginning of something. Trump’s inauguration is more like a regression.

King once noted, “Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle.” On Jan. 20, we’ll witness both the residue and the promise of that struggle, shaped by our tortured history.

The divergence between the two men — those perspectives on American history — is the hump we collectively can’t seem to get over.