At one point during the pandemic, the Rev. Dr. Shelly Wood was meeting regularly with a therapist, a spiritual director and an executive coach. She was working out and practicing yoga to manage her stress. And she was struggling to find a name for the miasma of fear, anxiety, urgency and grief she’d been experiencing since her church had been forced to stop in-person worship a month before Easter 2020.

She ultimately settled on a new word in describing herself.

“I was like, ‘This is despair.’ I had never experienced that before,” said Wood, the senior pastor at Orchard Park Presbyterian in Indianapolis as the world shut down. “I was pulling out all the resources I could to be OK.”

She was in good company. On Friday, March 13, 2020, the U.S. government declared the spread of COVID-19 a national emergency. By the following Sunday, states were ordering the closures of schools, restaurants, offices and houses of worship.

What many hoped would be a short-term inconvenience turned into a lengthy ordeal, with clergy worrying about worshippers as well as the long-term survival of their faith communities.

Those who hadn’t already embraced technology grappled with delivering virtual worship services and encouraging online giving. They endured the disruption of other in-person rituals — weddings, funerals, baptisms, communion — and disagreements over mask and vaccine policies. They fretted endlessly about how to provide meaningful pastoral care from a distance and questioned whether the connective tissue of the church could hold while quite literally being pulled apart. Some considered leaving ministry altogether.

Five years after the crisis began, pastors who have shared their stories with Faith & Leadership remain largely optimistic about the church’s future. While still grieving what was lost, they find comfort in the church’s ability to adapt and the resilience of their congregations.

We do church differently now, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

“I really believe in resurrection,” Wood said. “I really believe the church has a voice and will continue to.”

She remains proud of the way her church responded, creatively engaging its members and caring for the community at large. While still unable to gather in person, they sponsored drive-thru communion and a Palm Sunday parade, with members driving around town waving palms they’d picked up from the church’s parking lot.

Still, the responsibility she felt for the health and safety of her congregation weighed on her. Even after her church reopened, Wood said, her despair lingered. Not everyone came back right away — and some never returned. It was hard not to feel abandoned by them — or angry at God.

Ultimately, she bought pretty stationery and a nice pen to write heartfelt letters to a dozen families who hadn’t returned, members she’d had meaningful relationships with.

“I married your kid; I buried your dad; I spent Christmas with you guys. … You mean something to me. I just had to say goodbye,” Wood said she expressed to them.

She received a gracious response from one recipient, but the exercise itself brought her some peace and closure. And time helped her heal.

“I stopped dreaming about the people who weren’t there. I stopped looking out at the sanctuary and seeing empty pews and crying,” Wood said. “I let them go. I wished them well. And I sent them on their way.”

While it stung that not everyone returned when the doors reopened, the congregation attracted new members, many who’d initially participated in online worship. In April 2024, after almost 11 years at her Indianapolis congregation, she became the pastor at Old Presbyterian Meeting House in Alexandria, Virginia.

Wood felt called to the church, which dates back more than 250 years, because of its reputation for social justice initiatives. Her sense is that churches in general have become more missional in the wake of the pandemic, experiencing “almost a correction, … like a humility has come about, a sense of ‘we’re vulnerable, we’re human.’”

“Only if the people are the church will there always be the church. The church does not exist without humanity,” she said. “This isn’t something to take for granted.”

‘A better version of ourselves’

At St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, average in-person Sunday worship attendance has exceeded prepandemic levels, said the Rev. Dr. D. Dixon Kinser, the church’s rector. He credits much of that growth to the church’s willingness to continue livestreaming, which he said “is still the front door of the church.”

What were some of your community’s earliest adaptations?

Before the pandemic, he considered virtual services too “performative.” And even after the shutdown, when moving church online was almost an imperative, he worried about his ability to provide appropriate pastoral care for remote worshippers. That remains a concern, but what Kinser has heard from longtime members is that they like having options, “a bridge for the in-between times” when they can’t get to church.

In addition, the building’s neo-Gothic facade can be intimidating for those who’ve experienced “church trauma,” said Kinser, but virtual worship allows people to see past the imposing architecture and “get a taste of our energy, our music, our liturgy” before ever walking in.

The result has been a large growth in just about every demographic, but especially 20-somethings and young families — prompting a recently started young adult group.

Sunday church attendance hovered around 500 people prelockdown, Kinser said. It’s closer to 600 now, but the church has maintained some practices for those who favor a more socially distanced experience. Noon Eucharist each weekday provides access to the sanctuary without the crush of a Sunday service. Daily morning prayer service has remained online, where it has a large following of individuals who interact with and pray for each other.

The church’s ethos hasn’t changed, Kinser said, noting that St. Paul’s is still known for having a “twinkle” in its eye, for being welcoming and affirming and “open and articulate about Jesus Christ.” But now, the church offers more pathways for those interested in exploring something bigger than themselves.

“We’re smoking what we’re selling over here. And I think we’re a better version of ourselves,” Kinser said. “Our prayer around here is, ‘God help us not to break this thing you’re doing.’”

Gathering differently

In Fort Worth, Texas, the Rev. Dr. Katie Hays freely admits that she was the last holdout at Galileo Church when it came to offering virtual services. She didn’t want to contribute to a culture of more screen time but agreed to adding online worship in 2019 to provide LGBTQ+ worshippers access to an affirming congregation, no matter where they lived.

The online option was a blessing during the pandemic, and even when worshippers could return to the church’s Big Red Barn, Galileo maintained a part-time pastor to minister to the virtual congregation, called Inside Out. Hays thought the virtual community would want its own religious leader and activities, but Inside Out actually didn’t want to be ministered to separately from the in-person folks. When that part-time pastor got a full-time job elsewhere, the church didn’t fill the position.

“They feel very much a part of this embodied community,” Hays said.

Now, it’s just reflexive to make sure that whatever’s happening in person at the church can be replicated in some way by Inside Out worshippers. For instance, while the in-person crowd passes around a basket, collecting cards so congregants can write how they gave to the world the previous week, a volunteer usher guides online worshippers through a series of buttons they can click to add their thoughts to the mix.

All of their Holy Week activities, including a sing-along to “Jesus Christ Superstar” on Good Friday and a lakefront Easter sunrise service, incorporate online components. And it’s become standard operating procedure for in-person worshippers to turn and wave at the cameras to their online friends during communion.

Prepandemic, about 85 worshippers attended Galileo’s Sunday evening service; that’s down to about 75 now, but about 50 separate IP addresses log in to that service, from as far away as Hawaii and Florida, Washington state and New York. It’s hard to capture exactly how many people that is, and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) no longer asks her to track online attendance, which Hays said feels like a missed opportunity.

How does your community continue to serve those who favor more socially distanced experiences?

Using a multiplier of 1.7, which is common among faith communities, Hays figures online participants number between 75 and 80. Some who start online ultimately walk through Galileo’s doors or, buoyed by the support and affirmation they received from its online community, join other like-minded congregations around the country for in-person worship. But the virtual option remains essential for neurodiverse worshippers, those with mobility impairments or church trauma, and even just folks with busy schedules.

“That’s a big part of my church,” Hays said. “Some of the big postpandemic questions around Christian doctrine are going to be around incarnation. What does it mean that we can be in community but not in flesh together? That doctrine needs to be thought through anew as we think about online communities. What does gathering mean?”

‘A better day is coming’

How are you tracking nontraditional engagement with your congregation?

At Holy Trinity United Baptist Church in Washington, D.C., the pandemic forced the church’s elders to rely on the technological expertise of its younger members to move services, Bible study and giving options online, said the Rev. George C. Gilbert Jr., the assistant pastor to his father.

The move to virtual church was controversial at times, he said, with older members pointing out that the prophet Malachi instructed the faithful to bring their tithes to the storehouse — not to Cash App. But eventually, even longtime members found value in the church’s web-based offerings.

During lockdown, Wednesday evening Bible study migrated to Zoom, and it’s remained there largely out of convenience. Some members live 40 minutes away, and an online option provides time to come home from work, eat dinner with family and still participate. Members have also noted that they’re saving on gas and parking.

Holy Trinity still broadcasts Sunday worship services online, but about 80% of the church’s congregation are back in person. It’s hard not to mourn those who haven’t returned, but the reality is that church is competing with lots of things for people’s attention. It may take some time to “reignite” that flame for communal worship, Gilbert said.

“In the Black community, we say that your problems, your issues, your mountains that you climb may stretch you to find different opportunities,” he said. “And the pandemic stretched us. The pandemic taught us how to learn to do church in a different way.”

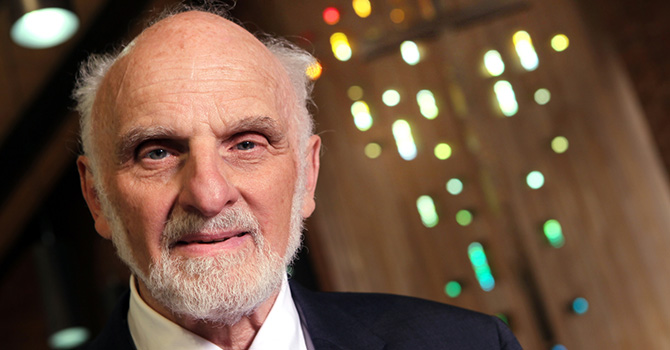

It also highlighted the importance of looking after one’s mental health, said Gilbert, who began attending therapy during the pandemic to address his loneliness.

His father, the Rev. George C. Gilbert Sr., suffered a stroke in December 2023. Gilbert said the “boiling point” for his father came when he tried to address a flooded basement, but “there was stress leading up to that day that had to do with church management and just trying to figure it all out.”

His father’s generation of clergy didn’t necessarily volunteer for therapy, Gilbert said, but Gilbert Sr. has been more open to it now since his stroke. It’s also become something that Gilbert and his father, who recovered and is in his 51st year of ministry, have started to address honestly with members.

“In our culture, members will come to us for anything and everything, and some of those things, we’re not qualified to address. We look at preachers and pastors as if we have all the answers. It’s hard to be vulnerable, especially when everyone is looking to you as a leader,” he said. “Historically, a pastor would try their best, but things are shifting. Now we can point folks in the right direction.”

The fear, uncertainty and political unrest associated with the last five years have been challenging, Gilbert said, but that’s why it’s been a “great time” to be a preacher.

“When folks are hurting or feeling displaced or feeling a need for a Superman or a Wonder Woman, this is the best time we can present the gospel, because it is the gospel that keeps us having hope that a better day is coming,” he said. “God’s already shown us if we made it through the pandemic, he’s going to help us make it through whatever’s coming.”

Conserving the congregation’s energy

A survey conducted in summer 2021 by the Hartford Institute for Religion Research revealed that almost 40% of clergy had seriously considered leaving ministry at least once the previous year. The Rev. Anna Tew was one of them. Nearly four years later, Tew said, “I think I’m happier with each passing year.”

While many of her colleagues had cited pandemic-related stress, racial tensions and political divisions as the reasons they were reconsidering ministry, Tew said her challenges were more internal.

She’d bought into the notion that she needed to be available around the clock, and she was exhausted. Responding honestly to the survey question was the first step toward addressing the problem.

She began spending more time with people who modeled a healthy work-life balance, and she shared her concerns with her congregation at Our Savior’s Lutheran Church in South Hadley, Massachusetts, where she has served since 2016.

“I learned to trust my church folks. They never expected me to be always available,” she said. “That was pastor culture. We learned to talk.”

How did the pandemic stretch your congregation?

She schedules regular breaks for herself now, noting how much more effective she is when she’s rested. “If I take an hour to walk the dog, I deliver a better sermon at church,” she said.

What’s more, her tiny congregation has also found ways to conserve its own energy. They rewrote their constitution, scaling back the size of their church council and splitting their ministry into three core areas (faith resources, faith development and faith practices) to better share the work and reduce fatigue. The church used to host a weekly coffee hour; that has become monthly, said Tew, noting that the conversations and snacks are even better now.

In-person Sunday attendance remains between 25 and 40, and the church continues to livestream worship services, which are still popular with first-timers, folks who are sick or on vacation, and those who prefer not to drive during New England’s icy winters. Tew is more aware than ever of all the things competing for her congregation’s attention and energy, so she tries to make their time in the sanctuary count.

“I try to provide an hour where they can take a deep breath and think about what it means to be in the presence of God and remember that they are loved,” she said. “To me, that gives them some armor so they can go back out and fight the good fight.”

‘We value togetherness’

The privilege of gathering shoulder to shoulder for worship can disappear in an instant, said the Rev. Dr. Sarah Taylor Peck.

“As we’re feeling increasingly isolated, alienated and divided, there are still places where we can gather, and they’re not a given,” said Taylor Peck, who became the lead pastor at Broadway Christian Church in Columbia, Missouri, in July after serving as the senior minister at North Canton Community Christian Church in Ohio for a little over a decade.

What expectations are a part of “pastor culture” that may or may not ring true for your faith community?

Her new church has endured significant transition on the heels of the pandemic; 14 of its 17 staff members are new as of March 2024, including Taylor Peck and her husband, Andrew, who serves as associate pastor. In many ways, congregations are still navigating pandemic-borne grief, which can present as anger, denial and apathy. When people show up with open hearts and a willingness to trust new leadership, that’s an honor, she said.

Witnessing people overcome so much change over the last five years has fed her resilience. Taylor Peck calls it “an act of resilience and even resistance” to get out of bed on a Sunday and commit to “sharing humanity” and praying with others, especially when faced with the trauma of the pandemic and ongoing political strife.

People have gotten out of the habit of being in community, particularly with those who hold opposing views, she said, but as we come “crawling out of COVID,” perhaps churches could be places where we learn what it means to be neighbors again.

“This is an opportunity for churches to say boldly and loudly and bravely that we value togetherness,” she said. “That collaboration, listening and love for one another still exist.”

Broadway Christian has about 600 members, and roughly half of them attend the church’s three in-person Sunday services. Only the last one, at 11 a.m., is livestreamed; earlier services include open prayer requests and a children’s moment, and those remain offline to preserve privacy. The church’s board is discussing ways to better serve the 40 or so worshippers who tune in online, she said.

Unfortunately, COVID isn’t the only thing keeping people socially distanced, Taylor Peck said. Political divides and the disappearance of basic civility are pushing people apart, and there are fewer spaces where they feel safe enough to come back together.

“I think sometimes churches imagine that they’re going to be the site of major transformation. We’re going to hold the best food drive ever and solve world hunger. Or we’re going to have the best clothing drive and clothe all the orphans in Africa,” she said.

Since there are major nonprofit organizations devoted to those tasks, perhaps the most profound contribution churches can make to humanity is simply throwing open their doors to welcome all comers, she said.

How is your congregation enabling acts of resistance and resilience in the face of trauma and strife?

“I actually think the best and most transformational act, the most holy act of the church, is continually bringing people together, to sing together, to pray together, to learn together and to learn how to be neighbors. It feels like sacred and important work to me, to lead an organization where people come each week … to wonder together about hope and what’s bigger than ourselves.”

Editor's note: After the publication of this story, Andrew Taylor Peck was put on leave after being arrested on a misdemeanor charge in connection with the theft of political signs.

What is the most transformational work of your church?

Questions to consider

- What were some of your community’s earliest adaptations?

- How does your community continue to serve those who favor more socially distanced experiences?

- How are you tracking nontraditional engagement with your congregation?

- How did the pandemic stretch your congregation?

- What expectations are a part of “pastor culture” that may or may not ring true for your faith community?

- How is your congregation enabling acts of resistance and resilience in the face of trauma and strife?

- What is the most transformational work of your church?