On a Friday night in 2019, the Rev. Dr. LaTonya McIver Penny miscarried. Less than 48 hours later, still bleeding and in pain — and without a word to her congregation about what she’d endured — she led the Sunday morning service at New Mount Zion Baptist Church in Roxboro, North Carolina, just as she had every week for the previous five years.

She now acknowledges that that should’ve been a sign, but she had been full-throttle for so long that it would take a devastating pandemic and a doctor’s stern warning to even entertain the idea of slowing down.

“I’m supposed to keep pushing and pushing, right?” said Penny, who reluctantly took four weeks of medical leave before resigning as senior pastor in fall 2021. “We’re not superhumans, but we don’t know that, because we don’t want to let anyone down. But the pandemic made me stop and pay attention.”

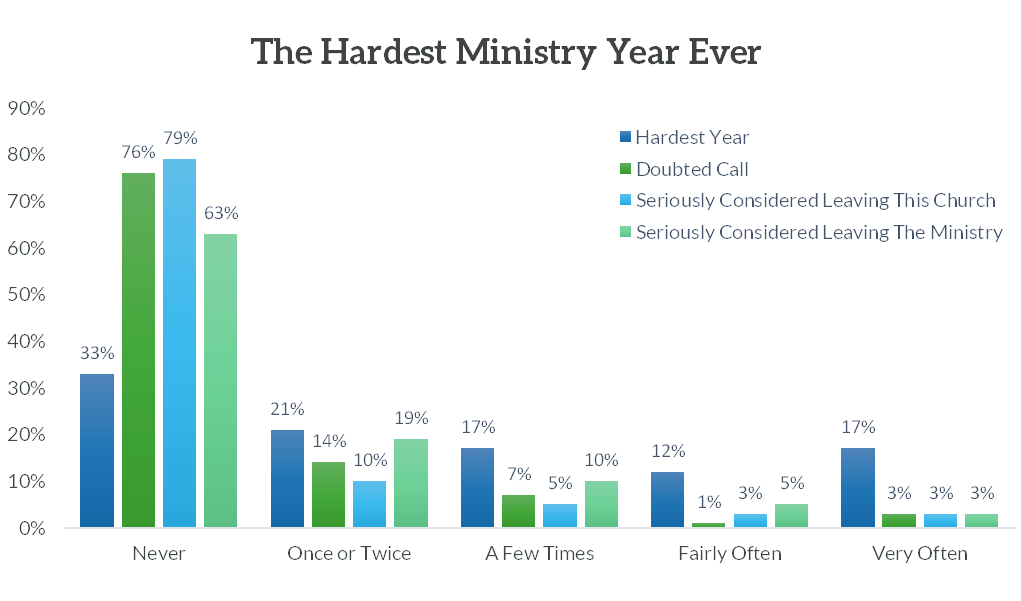

She wasn’t alone. According to surveys conducted last summer by the Hartford Institute for Religion Research at Hartford International University, 37% of clergy had “seriously considered leaving pastoral ministry” at least once during the preceding year, and 67% had thought at least once during that time that it was the hardest year of their ministry experience. Likewise, Barna Group, a research firm that focuses on religion, found in fall 2021 that 38% of pastors had considered quitting full-time ministry within the past year, up 9 percentage points from January 2021.

Those numbers fed speculation that the pandemic might be fueling a “great resignation” for clergy. But Scott Thumma, the director of the Hartford Institute for Religion Research, doesn’t see evidence of a mass exodus.

Thumma noted that 5% of the clergy who responded to the institute’s survey in summer 2021 had thought about leaving the ministry “fairly often,” while another 3% had done so “very often.”

“The 8% who said ‘fairly often’ or ‘very often’ — that’s not insignificant. If 8% of clergy truly did leave, you’d notice,” he said, estimating that to translate to at least 40,000 pastors.

“But it’s also definitely not almost 40%," he said, referencing the Barna study.

Most of the pastors who expressed serious frustration with their circumstances were already in difficult situations with struggling congregations before the pandemic ushered in controversies over in-person worship, mask wearing and vaccine policies, Thumma said. Racial tensions in the wake of George Floyd’s 2020 murder and political divisions associated in that year’s presidential election exacerbated those challenges; nevertheless, 63% of respondents indicated they’d never once considered leaving the ministry, he added.

Thumma and his team will continue tracking the pandemic’s effect on faith communities in a multiyear study — Exploring the Pandemic Impact on Congregations — funded by a grant from Lilly Endowment Inc. On the basis of the data he’s gathered so far and conversations he’s had with clergy, Thumma said he anticipates that more pastors will ultimately re-imagine how they do ministry rather than walk away from the profession altogether.

“The pandemic was the hurricane or the tornado, and we’re just now coming out of the basement … and seeing the devastation there. Now, the real work happens of putting things back together, of learning how to be church,” he said.

What are signs in your ministry and your life that you have ignored but need to attend to?

On the other side of the storm, Thumma said, “You could say, ‘Screw this; I’m going somewhere else.’ Or, ‘What plan do we want for our town? What are the things we didn’t like about it before that we don’t want to repeat? How do we reshape what church looks like? After the storm, how are we going to re-create the world?’”

For Penny, that started with a basic question: “What now?” She’d been the single mother of toddler twins when she walked away from her career as a public school teacher to pursue a divinity degree at Wake Forest University.

Inspired in part by challenges her children faced as preemies, she’d founded a nonprofit disability advocacy group called Mary’s Grace before graduating in 2013. She’d go on to build her ministry around inclusion and radical hospitality, making that the focus of her 2019 doctoral thesis while simultaneously serving as the first female senior pastor at New Mount Zion Baptist Church and continuing to run her nonprofit.

She was also putting in 12-hour days serving victims of domestic violence in her position as executive director of Family Abuse Services of Alamance County. The arrival of COVID-19 only heightened her pace as she juggled virtual services, her children’s educational needs, and the rising demands of both her congregation and those she served in the community.

By the time her congregation returned to in-person worship in September 2021, migraines, chest pain and stomach upset were a regular part of Penny’s day. Being back in the sanctuary “felt suffocating,” she said. Her doctor told her that something had to give.

In reevaluating her call, Penny said, she realized that the heart of her ministry had never relied on the physical church. She’d spent years teaching faith communities how to be more inclusive of those with disabilities or others who might not feel comfortable walking into a sanctuary.

Almost immediately, she and her husband, also a minister, founded Belonging Fellowship, a virtual church that emphasizes inclusivity. Because the church is online and there’s very little overhead, money raised by the congregation has fulfilled wish lists for residents of group homes, stocked the classrooms of first-year teachers, and helped families pay their rent and fill their gas tanks, Penny said.

Are there areas of ministry, congregational life or community connection that you recognize need reshaping or re-creating? What would it take to do that?

She also made a list of her “nonnegotiables.” After Floyd’s murder, she and her staff at the domestic violence shelter had published a statement affirming the lives of Black people — only to have a white board chairman order her to take it down.

Penny would not take a position, she decided, “where I have to fight for my Blackness.” She committed to spending more time with her children and invested in self-care, like exercise, eating right and saying “no” unapologetically.

In February, feeling healthier than she had in a long time, she became the executive director of the Laughing Gull Foundation, which supports grassroots efforts toward LGBTQ+ equality, higher education in prison, and climate and environmental justice.

“This has been what my soul needed. I matter on the other side of this,” said Penny, noting that she’s not doing less but rather more on her own terms.

“I think pastors are so busy praying for other people that they forget to pray and ask God, ‘What are you calling me to do?’” she said. “Just because you’re called into ministry doesn’t mean you’re called into the same space forever.”

‘Church shouldn’t hurt’

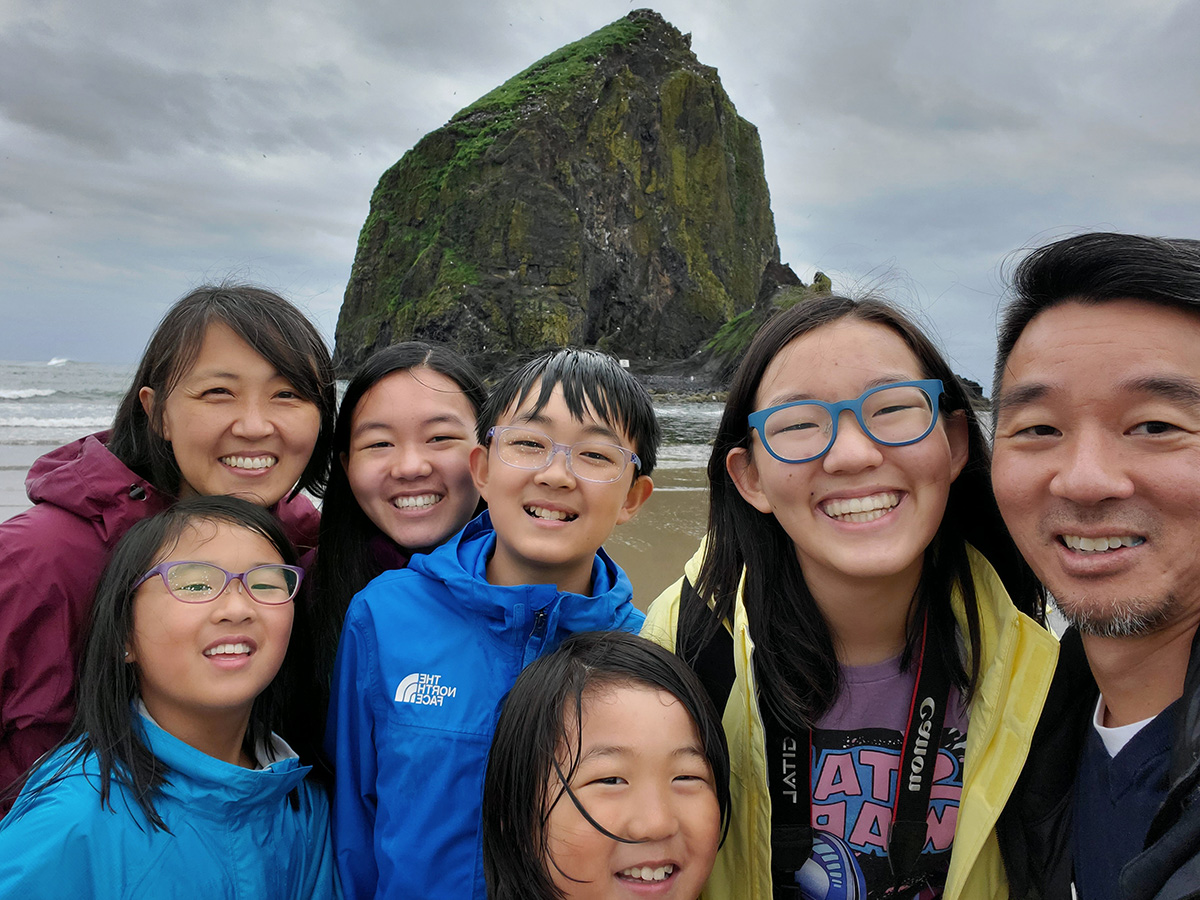

Like Penny, the Rev. Riana Shaw Robinson was exhausted long before the pandemic hit. The mother of four was still nursing her youngest — twins — while earning her seminary degree and serving as associate pastor of formation at Oakland City Church, a multiethnic faith community.

The only Black woman on the senior leadership team, Robinson organized the church’s first anti-racism conference and started a racial justice small group. Every time a high-profile case of violence against Black people made the news, Robinson felt responsible for processing it with her congregation.

“I felt I was responsible for all the people of color at the church. I needed to show up for them, be available for them, listen to them, be a safe space for them — and be responsible for teaching a bunch of white folks,” she said. “I’d hold all of that for so long, and then I’d come home and cry by myself.”

In March 2020, just as the pandemic hit, Robinson attended a three-day retreat sponsored by Liberated Together, an organization dedicated to empowering Christian women of color doing justice work in typically white, patriarchal spaces.

“I was already operating under the expectation that so many women of color operate under: ‘You will save all of us,’” she said. “They put me back together — me Riana, not me the pastor. We listened each other into life. What if that’s what church did? What if women of color showed up and said, ‘I’m so tired’ and the first thing people say is, ‘We believe you’?”

Following Floyd’s murder, Robinson said, she resisted requests from her church to lead its response “to give it legitimacy,” instead choosing a leave of absence, self-care and more time with her children. She still loved her congregation, but in September 2020, she let them know that some of her work, particularly on the racial justice front, was starting to feel “extractive.”

They asked for another year of service from her; she gave them 10 months, then, “feeling reduced to dust,” set off on a solo trip to Spain in July 2021 “to sit in old churches and weep and release.”

There had been so much noise over the previous 15 months, Robinson said, that she’d struggled to hear God’s voice. She briefly considered abandoning ministry altogether, but her “accountability group,” the women in Liberated Together, urged her to reconsider. She was still a pastor, they said, even if she didn’t ascribe to the white, patriarchal model of invincibility. “Where,” they asked, “do you feel freest to be honest?”

Robinson read Austin Channing Brown’s “I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness” and recited Psalm 23, subbing in female pronouns. She began working with women and gender-nonbinary people of color through the Faith & Justice Network and attending a Black congregation, a restorative measure she described as “like going to your grandma’s house.”

Are extra areas of responsibility placed on your ministry because of who you are? What are your expectations of yourself in that regard? Are there boundaries you can set?

“Church work is always hard. Ministry is always hard. I just don’t want it to be hard because I have to translate or explain myself or explain how I feel,” she said.

“Church shouldn’t hurt. What if church is where women of color show up and more isn’t demanded of them? They’re just seen and blessed in community and beloved?”

To that end, Robinson is launching a worship community “that unapologetically serves the needs of women of color, period,” she said. She envisions a bricks-and-mortar church with a virtual component for accessibility and hopes to have it up and running by Advent.

“It’s been a really painful year and a really beautiful year, where I feel like God has held me without demanding anything from me,” Robinson said. “I feel like God has been so gracious and gentle, saying, ‘I’m still with you.’”

‘A call is a dynamic thing’

The Rev. Anna Tew concedes that she was among the 3% of clergy who responded to the Hartford survey last summer by saying she’d considered leaving ministry “very often” the previous year. It wasn’t her congregation that made her feel that way, said Tew, the pastor at Our Savior’s Lutheran Church in South Hadley, Massachusetts, since 2016.

Instead, she said, her exhaustion “was an over-time thing.” She felt obligated to be at her desk eight hours per day, had fallen into a pattern of working on her days off, and was following social media accounts that made her feel guilty if she didn’t view “every little work task as a blessing,” she said. As a queer millennial, she was also doing a fair amount of “cultural commuting” within a largely straight, baby boomer faith community.

“I don’t think congregations get better than this, so if I’m not happy here, I might not be happy anywhere,” Tew thought. “That did lead me to really look at, ‘Do I really want to do this? Do I think it’s still worth doing?’”

Tew went on sabbatical in the summer of 2021, engaging in what she calls “the great unfollowing,” muting colleagues that made her feel guilty about wanting some downtime and “finding more clergypeople who had a healthier view of work and boundaries.”

She read Nedra Glover Tawwab’s “Set Boundaries, Find Peace: A Guide to Reclaiming Yourself,” calling it a “life-changer, career-saver,” and spent more time with nonchurch friends who modeled a healthy work-life balance.

“I didn’t know how to ask for what I needed — ‘Please don’t speak to me that way as a pastor’ or, ‘I’m not available right now; can we talk tomorrow?’” she said.

Which responsibilities drain you? Where are your models for a healthy work-life balance?

Tew also earned her CrossFit Level 1 certification and became a personal trainer. She noticed that when she received text messages from her training clients, she didn’t have that same tightness in her chest as when her congregation reached out. Perhaps, she thought, if she stopped treating every pastoral concern as if it were an emergency, she could better appreciate the pieces of the job she loved: the flexible schedule, the personal connections, “creating community around doing hard things” and following Jesus.

“I don’t think I would have done all that re-imagining without a crisis of international proportions,” said Tew, who notes that responding honestly to the survey question was the first step to acknowledging that she needed to approach ministry differently. “This is where I feel called right now, and I’m still careful not to hold it too tight. This is right now. Reevaluating our call is really important — a call is a dynamic thing.”

‘Something different’

By the time the pandemic struck, Ryan Timpte had been a children’s minister for almost 20 years, the last decade at Lafayette-Orinda Presbyterian Church in Lafayette, California, an 1,800-member congregation with “staggering” resources, he said. Pre-pandemic, the children’s programming ran parallel with adult worship services. When they moved online, he hoped the worship structure would pivot to appeal to the youngest members of the congregation, perhaps using “kid language” to explain how to pass the peace virtually or including some lessons on “why we do what we do.”

Instead, he said, the focus was on replicating what adults at LOPC had been used to.

“The pandemic could’ve been an incredible opportunity to open worship up, make it new. Instead, it was all about [keeping] the adults engaged and plugged in.” he said. “I am sure congregants enjoyed logging on and feeling just a little bit of what their normal had been. It’s just that their normal had cut kids out.”

His church wasn’t the only one to adopt that model, he said. Timpte maintained contact with a group of colleagues who had, individually, come up with creative ways to keep children engaged but had done so largely independent of any support from the decision-making bodies at their churches. With more demands for pastoral care and other church resources, Timpte said, he understood why children’s ministries were not the first priority.

“But it’s just one more way in which the church reflects society,” he said. “Children’s ministry is a lonely thing even in the best of times, and the pandemic was not the best of times. With all the resources I had, I still couldn’t change the system. And if I couldn’t do it there, I couldn’t do it anywhere.”

In fall 2021, his wife was offered a job leading university and young adult ministry at a Presbyterian church in Berkeley. Timpte said it felt like the right time to leave, not just his church, but church-based ministry. He committed to being a full-time dad to their two young sons, ages 7 and 3.

Then a new opportunity opened up. A member of LOPC who had volunteered with the children’s ministry when his own kids were little was launching a startup toy company dedicated to following sustainable practices, educating kids about the environment and keeping plastic out of the ocean. Would Timpte like to join as creative director?

“I’m committed to making the world a better place for children, and for 20 years, I thought that was through the church. Now, I think it’s maybe something different,” he said, noting that his calling hasn’t changed, just where he uses it. “There’s a whole other way to make the world a better place.”

How has the pandemic affected your sense of call or where you might serve it? What could that look like?

‘Hope and redemptive purpose’

In an article published by Christianity Today in February, the Rev. Peter Chin acknowledged that he was considering leaving the ministry after 20 years. His Methodist congregation, Rainier Avenue Church in Seattle, had survived the “run-and-gun” style of the early days of the pandemic. But entering the second year, disagreements over masks and vaccines mounted, and relationships among the traditionally tight staff began to fray, injecting “a paralyzing degree of complexity and controversy” into every decision he made, he wrote.

“Even in the best of times, pastoral ministry has always felt like a broad and heavy calling,” he wrote. “But the events of the past few years have made it a crushing one.”

The response he got from colleagues let him know he was not alone. Each had felt crushed at times by the pressures of the pandemic, but no one seemed to have any great advice on how to handle them.

“Everyone was in the middle of this torrent, swimming at the same time,” Chin said.

Also, no one could believe he’d acknowledged his concerns so publicly in his essay.

“The unanimity of the response was, ‘I feel seen, I feel heard, but I don’t feel I can say these things, because I don’t know how it’s going to come off with other people,’” Chin said. “A lot of the struggle for pastors is this cultural expectation that pastors don’t feel this, because they’ve got a higher calling. But it’s healing to say it and to put it out there and be free from the secrecy of it.”

In May, Chin credited that honesty with leading him to a better place. He said he’s spoken truthfully with his congregation about the stress and grief associated with this time, as well as how God’s love for him — and the expectation that he will love others — has served as an anchor. He’s also openly addressed staff conflicts, leaving no room for gossip or misunderstandings.

“Honesty has really panned out for us,” Chin said. “We need to go beyond creating the illusion that everything is fine, and truth-tell.”

Much of what has drained pastors predates the pandemic, he said. But the pandemic has quickened the pace. Rather than viewing this as destructive, why not view it as corrective, a chance to shed traditions that weren’t working and embrace new practices that sustain pastors and their congregations?

“This is an opportunity for us to re-imagine and reclaim some things about the church,” Chin said. “In God’s community, there’s hope and redemptive purpose for even the hardest things.”

Questions to consider

- What are signs in your ministry and your life that you have ignored but need to attend to?

- Are there areas of ministry, congregational life or community connection that you recognize need reshaping or re-creating? What would it take to do that?

- Are extra areas of responsibility placed on your ministry because of who you are? What are your expectations of yourself in that regard? Are there boundaries you can set?

- Which responsibilities drain you? Where are your models for a healthy work-life balance?

- How has the pandemic affected your sense of call or where you might serve it? What could that look like?