On Sunday, Feb. 16, people gathered after worship in our church’s fellowship hall. It looked, in many ways, like a regular potluck. A large pot of soup was set on the buffet, someone dropped off a bag of clementines, and people brought lots of baked goods. As the food came in, folks who know our church kitchen as well as their own pulled out plates and serving utensils.

There was a mix of people — some of the 125 folks were members of our congregation, but many were neighbors, friends and co-workers. Word had gotten out.

Earlier that week, we sent out an all-church email with the subject line “Organizing Against Cruelty.” It was one way we could respond as the church to the radical disruption in our community caused by the new presidential administration.

Our church, a 375-member PCUSA congregation, is located about 3 miles from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. We have 15 to 20 families in our church whose livelihood depends on work for the CDC, which was among the first targets of spending cuts by the new administration. The agency had become a “public enemy” during COVID because it advocated for restrictions on personal freedom in order to save lives. Now I was receiving emails and text messages from people afraid of losing their jobs.

You don’t cut “an agency.” The CDC is not nameless or faceless. It is a collection of rather remarkable human beings. I am a pastor for some of them. They sing in our choir, play games with our youth group and lead our congregation as elders. They also keep humanity safe from illness. In my experience, they are people of deep faith, who love God and others — commitments that align with their work at the CDC.

My CDC-affiliated congregants were not prepared for this. They all know that when a president is elected, priorities can change; several had shared stories about job pivots under a new administration. But they are stunned that a president could demonstrate such disregard for something as foundational to the common good as public health, and they mourn the loss of the programs they have worked so hard to build.

“Those of us in global health and development are not in it for the money or to push some sort of radical agenda. We want to ensure that people do not die of things like contaminated drinking water, measles, polio, mosquito bites or HIV,” one of our CDC-affiliated congregants told me.

The people I spoke to for this essay asked to remain anonymous, fearing repercussions.

Virtually all their work has been put on hold as they await impending cuts. There has been no explanation from the administration about where there is waste or fraud at the CDC or why the positions being eliminated are not essential to public health — some of the reasons the administration has given for the cuts. It’s randomly inflicted harm.

“The field of global health and development is being decimated like a toddler swiping at a Jenga tower,” one congregant said. “I feel such grief over the lives of U.S. citizens and people across the world that will be lost or irreparably harmed by these changes.”

They are grieving the loss of lives and the loss of programs that have proved to work. They also are grieving the loss of their vocation. Each knows their calling is aligned with the ministry of Jesus, an itinerant healer, who made healing the sick a sign of the inauguration of the kingdom of God.

“My career is truly how I live out my faith — using my hands and feet to care for those whom the world would rather forget,” one told me.

Another said, “I’m a resilient person. My job is hard — I travel to places where I deal with health emergencies, and so I work all the time with people experiencing real trauma. I can deal with a lot of things — I usually just put my head down and think, ‘We’ll get through this; it can’t go on forever.’ But this feels different. I’ve never had my fundamental worth so questioned.”

What can a church do in a moment like this? Pastoral care, for one. Not only the one-on-one engagement with the pastors but also the strength that comes from belonging to a community of people who love you. That is the real help in a time of trouble. We need to be seen. We need to feel valued.

When authority figures question your worth and have the power to make you feel worthless, you need a community of people that affirms a truer narrative: “The work you do is amazing. You are amazing.”

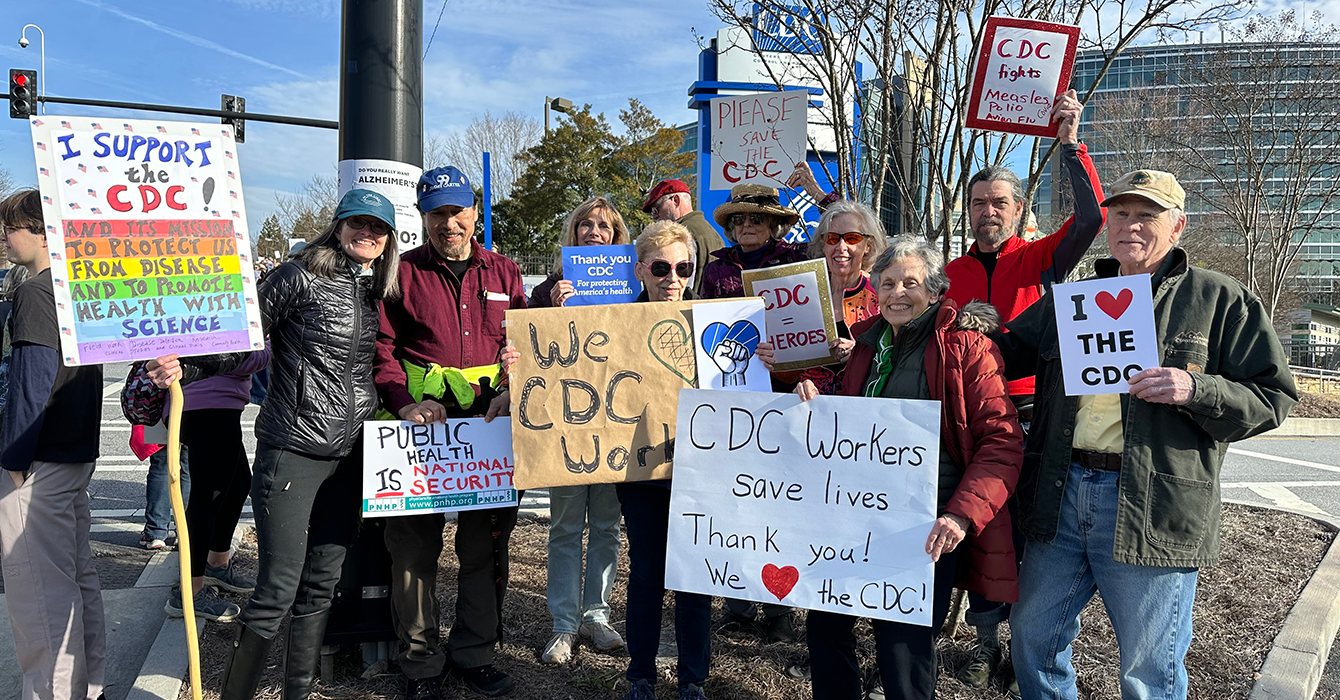

Some of our church’s retired members are among those who now stand outside the gates of the CDC holding signs saying “We love the CDC” and “Protect Public Health.” Several people have mentioned how much this small gesture of support buoys their spirits.

Our finance team at church has a reserve fund ready to help members who lose their jobs pay their bills and rent. We are also quietly preparing for a loss of income if our CDC members are fired.

The Organizing Against Cruelty community gathering was a second kind of response, bringing people together to act. In the first few weeks of the new administration, many people expressed something like, “This feels terrible. What can I do?” Older adults especially may not be online and may not be plugged in to networks for action and activism.

At the gathering, we invited people to share resources with one another — one hungry person telling another hungry person where to find bread.

We talked about how to contact our legislators and what groups are active in our community. We set up breakout rooms for specific needs — support for transgender poeple, caring for immigrant neighbors — and a room for federal employees to share their experiences and talk without fear of recrimination.

While this role for the church, as a steward of the power of grassroots organizing, is important, there is another, perhaps paradoxical role the church can play: we can hold our human suffering as part of a larger story.

One of my CDC members said, “Lent always feels timely, but this year, my soul desperately needs it. Observing Lent helps prepare for loss, and the reminder that Christians have been marking this season through different crises and times of fear and change is welcome at this moment.

“We don’t have to do everything perfectly, but we do have to take care of each other, knowing we will all meet the same end that Jesus did on the cross.”

Not all suffering is redemptive, and the suffering of my congregants and other federal workers right now feels particularly unnecessary. But the church, when we are faithful, helps us understand that our suffering is woven into the great story of God’s love.

Our sensitivity to this suffering helps us be agents of healing. When I asked one CDC employee how she is holding up, she said, “It’s awful. … But I know that I am going to be fine.”

She told me about her volunteer service with a partner organization supporting refugee families and said, “There are so many people who are much more vulnerable in the face of this cruelty than I am. It’s them I’m worried about. I’m going to be taking care of them.”

You need a community of people that affirms a truer narrative: “The work you do is amazing. You are amazing.”