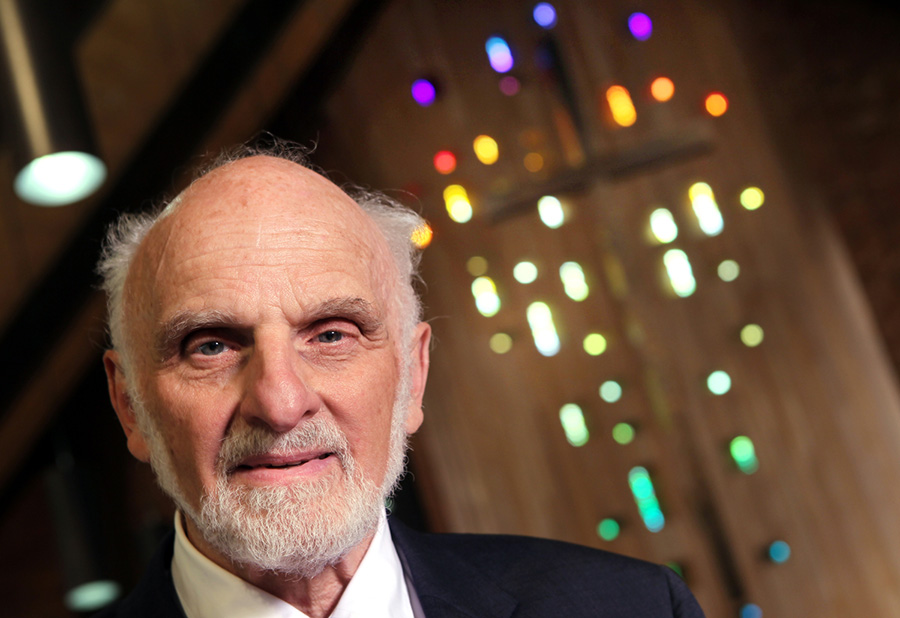

When Walter Brueggemann died June 5, 2025, Jerusha Neal saw a lot of tributes to the biblical scholar from preachers.

On her social media feed, a quote circulated: “The prophetic tasks of the church are to tell the truth in a society that lives in illusion, grieve in a society that practices denial, and express hope in a society that lives in despair.”

Brueggemann’s conception of the church’s prophetic task has gripped many preachers for more than 50 years, during which time he wrote over 100 books. Neal, herself now an associate professor of homiletics at Duke Divinity School, remembers encountering his work as an undergraduate and studying it in seminary.

Neal spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Chris Karnadi about Brueggemann’s influence on the field of preaching and the work of preachers and why many preachers found his work so meaningful. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Why do so many preachers love Walter Brueggemann?

Jerusha Neal: I think one of the reasons why Walter Brueggemann has just a very special place in the hearts of so many preachers is he really had preaching’s value, its import, and even something of its method at the very heart of how he did biblical work.

There was a way in which he sort of claimed preachers as his audience, and I think that’s part of why so many preachers claimed him back. He saw them and saw the difficulty of what they were trying to do.

And I think part of that goes to the work of his braid of hermeneutics. Yes, he kept Scripture’s historical context in view, but alongside that, he braided sociological analysis both of the past and the present in leveraging what he really saw to be a text’s core theological claims.

That particular braiding may seem an obvious thing that preachers do every week. They take a biblical text, they think about, “Well, what’s the context in which it was written? And then what is the context now? And what does that say about who God is?”

That may seem like a familiar move. But when Brueggemann began writing in biblical studies, he was actually getting some unfamiliar bedfellows into the room together, setting the table rather broadly.

This means, firstly, that his work has always had a very robust interdisciplinary nature to it. And secondly, he has always had the church in view when doing his work, even when he was writing in a very academic tenor. That was fundamental for him. And so as a practical theologian myself, I look at his work and I appreciate that the urgency of that press toward faithful witness was always a part of his character.

Because of that, his biblical scholarship was recognizable to preachers. It looked like something they grappled with each week.

For me, one of the gifts of the last year was being approached by a journal to write a review of one of Brueggemann’s recent books, “The Emancipation of God.” It was really a collection of blog essays from his online column.

In those essays you get a little glimpse of the books that were on his bedside table because he cites these people as he’s talking. And oh, my goodness. The breadth of those titles! You see clearly that, even into his 90s, he is reading works on climate care, climate justice, social resistance, and bringing that into conversation with the biblical text.

That sort of creative dialogue that marks his work between past and present, between church and society, between the preacher and God and the preacher and God’s people is very familiar to preachers. There’s a homiletical process, I think, to his biblical work. I think preachers get him.

F&L: What drove him to write so many books?

JN: Well, I didn’t know him personally. So there are people who knew him as a friend who probably could speak more to that question. But I’ll tell you part of what I think it is. He had an intense love for the church and belief in the value of the church, and he had an intense understanding of the church’s failings.

He was part of us. He claimed us. He was with us. When you love a people that much, and you also have such a lived awareness of our domestication by the powers that be, particularly here in the North American church, there is a kind of holy rage that fuels a lot of pages.

It wasn’t just a scold. There was a deep belief in God’s ability to transform a broken world through the ordinary witness of this ordinary community. And I just think that hope drove him. He felt the weight of speaking truth, grieving and speaking hope.

He was not one to place heavy burdens on others and not carry them himself. I think if he was going to ask preachers to do that work, he was going to do it with them to the end.

F&L: Why do you think preachers turned to him as a biblical scholar?

JN: Preachers felt seen by him and felt they could trust him because they saw a person marked by deep spiritual practice.

This is a person who began his lectures with prayers that were so carefully constructed that they were collected into books. There was this sort of commitment to prayer, commitment to poetry, commitment to protest, commitment to praise, commitment to doxology.

He took these core spiritual practices and placed them at the center of how it is that we understand Scripture itself. That to understand the biblical text is to see the text itself engaged in these practices.

But it’s not just ideas or content or historical information. They’re actually enacted practices of God’s people, lived out — that we have windows into, but that also are calling us out into active faithful action in the world. So spiritual practices are key to his work.

Another reason I think he’s so claimed by preachers is his firm conviction that preaching proclamation and prophetic imagination matters. It matters to the world.

Right after he passed, a quote from Brueggemann went around on my social media feeds. It was a beautiful quote by him: “The prophetic tasks of the church are to tell the truth in a society that lives in illusion, grieve in a society that practices denial, and express hope in a society that lives in despair.”

I think part of why that resonates with all the preachers on my social media feed is because it grows out of a sense that the words we say from the pulpit matter. There’s also this line at the end of “Finally Comes the Poet” where he says, “We have only the Word, but the Word will do.”

And by that, he certainly doesn’t mean that action and transformation and justice work is not needed. Part of what he means is to do that work, the kind of imaginative proclamatory practice of the preacher, and then the biblical scholar, matters.

In the very last essay in “Emancipation of God” — so he’s writing this very late in his life — is this question about the relationship between the emancipation of the neighborhood and the work of biblical scholarship. He takes on this rising tide of Christian nationalism that is in our present context and talks about how proof texts are not going to cut it in this day and age. We need biblical scholarship that is deep and robust. And we need it not for the sake of institutional maintenance, we need it for the sake of the preservation of life really, in our communities.

That is encouraging to preachers because I think there is a crisis of relevance for many preachers. They worry, “Does what I say to 50 to 100 people from this pulpit on a Sunday morning make any real difference? Does all the work that went into it, all the study that took it to shape that word, the training that happened, does it matter?”

And Brueggemann just was clear that this speech could actually create an alternative to the dominant consciousness of the day. It could turn the tide.

F&L: How did you see his work change over the years?

JN: He was not afraid of tension. He steered right into conflict. I think good preaching often does that too.

He was not afraid to grow and change. When you go deep into a tension for long enough, you realize that you yourself are implicated, that you yourself perhaps aren’t as sure as you thought you were when you started.

And I’ll give you a couple examples of this that I see in his work, ways in which I have seen him grow and change, as someone who came after him, has always really respected him, but has also seen shifts in the emphases that he makes over time.

He has always had such an emphasis on the freedom of God. This is a big God, a free God, a free Word, a free text calling forth a free people. Emancipation, that’s what it’s all about.

And in some ways there was always some tension that he had with other biblical scholars who emphasized, “Well, no. The core to God is his covenantal fidelity, right?”

As Brueggemann moves forward in his work, you begin to see that he resists a binary in that tension and instead allows that rich conversation with his colleagues to move him deeper into the definition of his terms.

I’ve done a lot of work on climate justice. And so by now, his book “The Land” is a classic on thinking through the significance of place. Given all of his emphasis on emancipation and freedom, he talks at one point in that book about how emancipation isn’t the core claim of Scripture, but it’s about belonging. It’s about rootedness.

In this, I hear careful listening to his colleagues and also to the complexities of the biblical material. Not pressing that biblical material into an easy simplistic sound bite, just letting it work on him. And by the time you get to these essays in “The Emancipation of God” that were just recently published, he has this lovely definition of emancipation, he talks about emancipation as the freedom to be responsible to neighbor and to creation and to God.

When I see that kind of growth and change and deepening and nuancing, I have so much respect for that. Because we live in a season where we sort of map out our theological territories and we build our theological walls. This happens in the church, and it also happens in the academy. And to have enough hope to say, “Hey, I think there’s something beyond my fence. There’s something actually that is bigger than my understanding.” And to keep striving for it and desiring it, there’s a humility in that.

He also believed God was real, and that really matters. For all of his emphasis on rhetoric, when push came to shove, there was a real God at work behind that text. And that God, that big God, was who spoke, and the rhetoric was a response to a God who was active and alive.

And that’s really core to my teaching of preaching, that we don’t simply teach about God or preach about God, but that we respond to a living God that speaks now. And in through the biblical witness, yes, but to particular situations and particular communities with a word of life.