When she entered high school, Jacinta Merritt was overly shy; as a freshman, she wasn’t sure how to talk about her story or what she wanted to do with her life.

Five years later, the now 19-year-old is a leader, business owner and university student studying business management.

Beyond that, she has a big passion: helping people understand that everyone is a human with a story, that each person has feelings and emotions to be respected and discovered, that resolutions are possible without rancor.

Merritt learned this through New Community Outreach (NCO), a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving life in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago by focusing on trauma-responsive support and violence prevention.

The organization, founded by New Community Covenant Church in 2017, seeks to foster relationships and flourishing by offering tools to increase mindfulness and improve coping skills. Their work is centered on restorative practice and restorative justice, largely with youth.

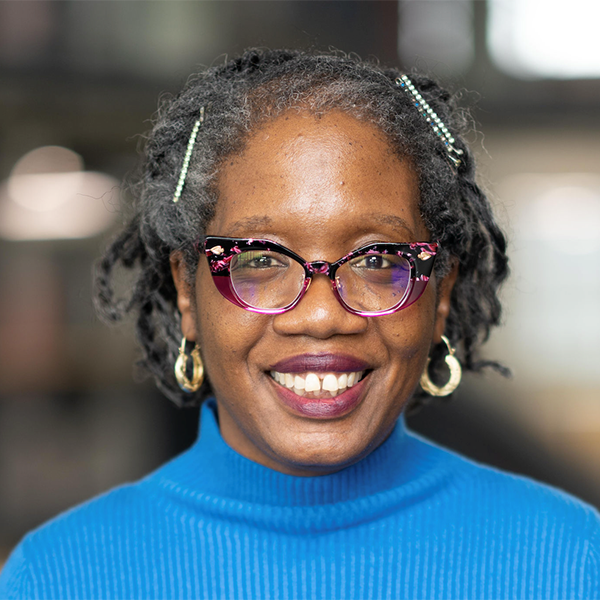

“That’s the philosophy behind our mission, which is all about cultivating restorative spaces for healing, reconciliation, and flourishing of our young people and our neighbors in Bronzeville,” said Sonia Wang, a church member and former educator who became executive director of the nonprofit in 2020.

“When we take time to center each other’s humanity within our interactions, we pursue long-term healing and flourishing in how we interact with one another and our community,” Wang said.

New Community Outreach pursues restorative justice through four programs and initiatives, including a community garden, managed in partnership with a local elementary school; an annual back-to-school event; and a commitment to providing intentional space for community engagement in restorative practices.

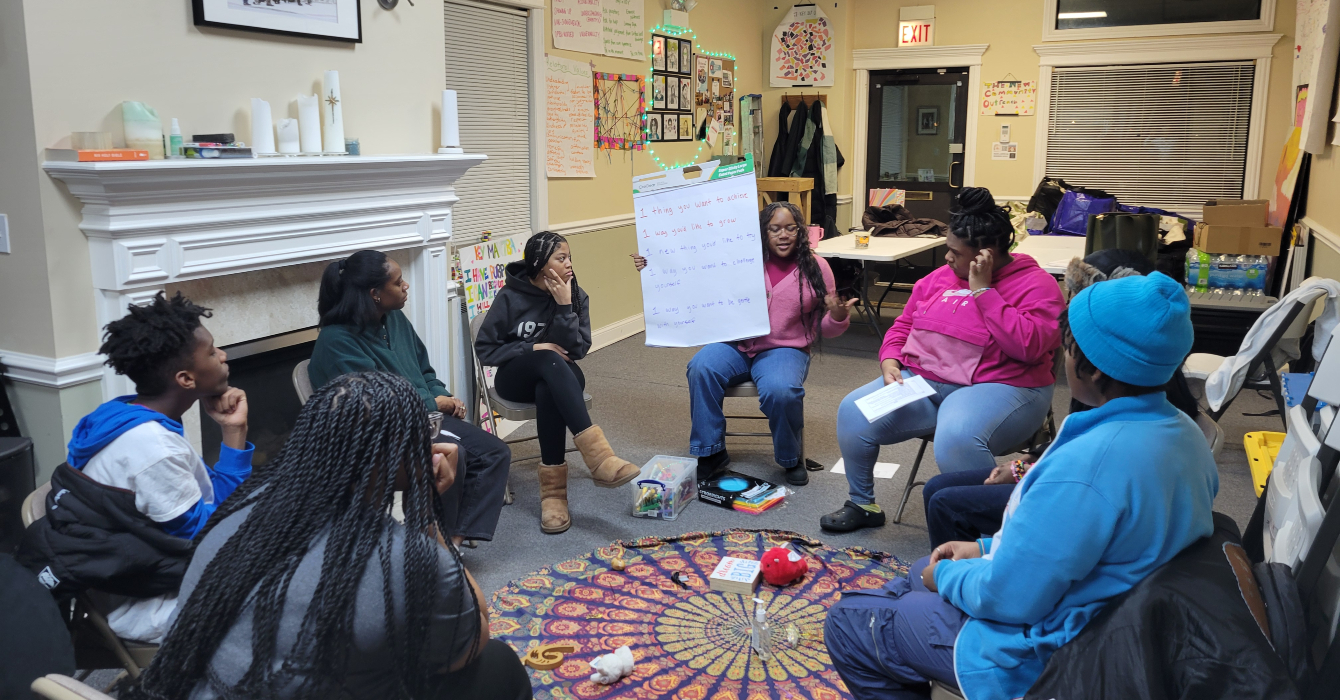

Their flagship program is for youth. At its heart are “circle sessions,” in which high school students gather weekly for structured conversations facilitated by trained “circle keepers.”

Merritt took part in a circle as a student, transforming from that shy, uncertain freshman to a confident young woman through the program’s restorative space where she could talk about anything. She attended program offerings multiple times a week, eventually becoming an intern in the NCO office. Even now, although she lives in Peoria while studying at Bradley University, she sometimes joins Saturday sessions for high schoolers and alumni.

“I just really felt comfortable and safe, so that’s what allowed me to continuously grow,” she said. “It’s allowed me to speak my truth and discover who I am.”

From church mission to neighborhood mission

Bronzeville, which is 4 miles from downtown Chicago, has a storied history. Once known as “Black Metropolis,” the neighborhood has been home to luminaries including Louis Armstrong, Ida B. Wells and Gwendolyn Brooks. But it also has been affected by a conflux of public policies, from newly built highways to demolished public housing.

What are some ways in which you can incorporate restorative justice principles into your leadership and ministry settings?

It has a current population of about 53,000 people and was settled during the Great Migration and has a median income of around $40,000, compared with $72,000 citywide.

In 2019, Bronzeville was selected as one of 10 Chicago neighborhoods identified for extra investment by the city. Then-Mayor Lori Lightfoot, introducing the initiative, noted the history of the communities’ decline: “The viability of these once thriving neighborhoods has been undermined for the past 70 years through substantial population losses, disinvestment, crime and other systemic issues.”

A 2024 City Bureau report noted that recent Bronzeville development includes new homes, but at prices that exceed the average resident’s ability to buy them.

In 2015, New Community Covenant Church, which has a campus in Bronzeville, took part in a community assessment. In response to the findings and inspired by the work of nearby Bright Star Church and its Bright Star Community Outreach organization, New Community Covenant Church founded NCO as a nonprofit with a focus on Bronzeville.

“Central to our Christian faith is Jesus’ instruction to love our neighbors. This is foundational to our understanding [of] being the church. The nonprofit allows us to love our neighbors in a manner that is strategic and collaborative,” said David Swanson, the pastor of New Community Covenant Church and founder of NCO.

How can Christian leaders acknowledge historical harm from disinvestment and systemic inequalities while fostering healing and flourishing in their own communities?

These efforts aren’t designed to grow membership or even directly benefit the congregation, and though the church maintains a connection to NCO legally and financially, and NCO benefits from the work of church volunteers, the nonprofit is not a faith-based organization.

“It’s a structure that empowers the entire congregation to be obedient to Jesus’ teaching in our particular place,” Swanson said.

The NCO headquarters is about a five-minute drive north of the church’s worship space, past a playground and high-rises and many stately red brick buildings with ornate details.

Wang herself attends New Community Covenant Church, which seeded the Bronzeville congregation in 2010. Church leaders, she said, saw the connection with NCO as part of an intentional larger effort to serve the community.

“Our vision was to maintain this connection both for the good of the congregation and the nonprofit,” Swanson said.

Serving the community helps restore flourishing in a place where the land itself has been warped by disinvestment, Wang said.

How does Scripture support the shift from an individualistic mindset to a community-oriented one, and how can this be applied in your leadership practices to lead counterculturally?

“There has been harm that’s been done to the Bronzeville community because of systems, and part of that is what we’re also striving to restore — it’s not just between people to people,” she said. “By really prioritizing this space of relationship, relationship to community, relationship to our neighbors, what we’re really thinking is, ‘How do we shift the idea of community attachment?’”

A safe space for youth to be honest and vulnerable

New Community Outreach’s goals are communitywide, but the process is one of building relationships, starting with young people.

In 2018, NCO launched a pilot program in a local high school involving the first candid conversations using the circle process.

Rooted in Indigenous practices, circles focus on the sacred nature of recognizing the importance of every person taking part. The NCO program is now offered in three local high schools, where students meet throughout the school year with two adult circle keepers, who facilitate the confidential conversations.

Participants sit in a circle and pass around a symbolic “talking piece” like a stone or stick; only the person holding the object can speak. Participants commit to listening to others as well as sharing their feelings and thoughts. The facilitators, who take part in the circle, make sure that everyone has a chance to speak.

How do you prioritize relationships in your leadership to cultivate a deeper sense of community attachment among those you serve?

The process is used in many settings by many groups; the NCO circle program allows students to process their feelings, experiences and circumstances involving trauma of all kinds, including gun violence, and to build coping skills like meditation.

“They’re not coming into circle as friends. They’re coming in as strangers, and they’re realizing, ‘Oh, we have things in common I never thought of,’” Wang said. “That’s where the beginning of repair, just a different way of living, can come out. And that’s really what we believe in.”

Merritt remembers seeing a flyer about the circle and coming to a session. She didn’t speak up much at first, but eventually her circle tackled topics like identity and generational trauma.

Merritt says she’s a different person after investing time in circles. She’s dedicated to leading with curiosity and care and has started her own hairstyling business called Simply The Look. She attributes her new confidence to the work she did with NCO.

“It’s helped me in so many aspects. What’s coming to mind is public speaking, being comfortable with telling my story,” she said.

This year, 200 students attend circles in Walter H. Dyett High School for the Arts in Washington Park, Daniel Hale Williams Preparatory School of Medicine in Bronzeville and Bronzeville Scholastic Institute. A pilot program with third graders at Jackie Robinson Elementary School meets weekly as well.

Along with circles, NCO offers Saturday sessions, optional one-on-one mentoring, and after-school programs, as well as a summer leadership program. Students like Merritt can move along a leadership trajectory, training as circle keepers with NCO partner Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation; three to four students work each year as interns at NCO.

By taking part consistently over the course of months and working with adults who are committed to this restorative way of engaging, Wang said, the students see benefits that go deeper than those they might gain in a single workshop or class.

Through creating consistent safe spaces, Wang hopes to both heal and empower.

“A group of people start off as strangers, and by the end of the school year, it’s completely different,” she said.

Wang noted that students have told her, “In the beginning, when we first started meeting, I didn’t like this person or I thought I could never get along with this person. Now, they’re like family to me.”

Widening the circle

Wang trained as a circle keeper in 2019, and in 2020, after 15 years as a public school teacher and administrator, she became the executive director of NCO. She was excited to be part of building something that felt important to the community and especially to youth, even though that year proved to be a time with unexpected challenges: the pandemic made circles virtual.

Wang was touched and inspired by students still making the effort to come during such a rollercoaster period.

Helping youth open up to each other at school may not seem like an obvious, immediate benefit to the community, but Wang noted that it builds resilient, empathetic, emotionally intelligent and strong adults.

Investing in this type of work with children and teens matters because it’s investing in the next generation. New Community Outreach’s circles can build a community’s resilience by engaging the younger generation — who one day may anchor the community — in discussing a variety of issues in a safe and restorative space.

Wang noted that we live in an individualist society. “We forget the importance of each other, this shared collective experience,” she said.

“This whole notion [that] ‘stranger’ means ‘enemy’ kind of starts shifting, and instead ‘stranger’ just means ‘someone I haven’t tapped into yet,’” Wang said.

It’s part of the larger effort toward restorative justice, which Wang described as recognizing the history of oppression in a community and how that oppression has affected it. In Chicago, that means acknowledging disinvestment and years of inequality like redlining.

It is equally important, Wang added, to then ask, “How do we intentionally pursue opportunities for healing, reconciliation and flourishing, so that we move towards liberation?”

Last year, NCO served at least 1,700 people in the four program areas and had 124 volunteers participate. The nonprofit raises money from sources including individual and partner donations, grants, and events, and through campaigns to fund the budget, which has grown to $381,000 for the 2025 fiscal year. There are four part-time staff members, and Wang is full time, utilizing community volunteers for most of the events and programming.

Each program or initiative is geared toward a challenge NCO hopes to solve; for example, the Garden to Table program offers free produce from NCO’s community garden to neighbors who face food insecurity.

The Back to School Fun Fair offers activities and school supplies, bringing together students, community members and community partners like the Chicago Fire Department and Illinois Action for Children, which administers the Child Care Assistance Program in Cook County.

How does reframing the idea of a stranger from “someone to avoid” to “someone I haven’t connected with yet” challenge the way you welcome and build relationships in your leadership?

And NCO extends its restorative practices to the community more broadly. It hosts a quarterly community circle where neighbors can pause and reflect. It also offers circles to NCO partners. This last piece is less structured than the school program, but Wang says that’s intentional.

“We don’t want to [be] so busy with other things that we can’t actually be in partnership and in community,” she said.

All the work is geographically focused.

“Our commitment is to the Bronzeville community. So that’s something that we are intentional about. We are not Chicagowide,” Wang said. “This is something that, similar to the church’s commitment to this community, we see that as the space that we’ve been called into.”

From shy teenager to confident college student

As students become adults, the impact of the program ripples outward. Some, like Merritt, become leaders themselves.

“Our young people have creativity and untapped courage and bravery that — sometimes as we grow older, there’s kind of this cynicism that comes through,” Wang said. “What I love is that when we do allow our young people to lead, really beautiful things come through.”

Cycles of community violence lessen when people feel attached to their communities, Wang said, and strong attachments can mitigate the impact of childhood trauma.

For Merritt, the benefits of her experience with NCO continue. The biggest impact for her?

“Peace. That’s really what it is,” Merritt said. “When you do those things, when you speak your truth, when you live your life how it’s supposed to be, you feel peace.”

Questions to consider

- What are some ways in which you can incorporate restorative justice principles into your leadership and ministry settings?

- How can Christian leaders acknowledge historical harm from disinvestment and systemic inequalities while fostering healing and flourishing in their own communities?

- How does Scripture support the shift from an individualistic mindset to a community-oriented one, and how can this be applied in your leadership practices to lead counterculturally?

- How do you prioritize relationships in your leadership to cultivate a deeper sense of community attachment among those you serve?

- How does reframing the idea of a stranger from “someone to avoid” to “someone I haven’t connected with yet” challenge the way you welcome and build relationships in your leadership?