A few weeks before Christmas 1994, Maggy Barankitse approached the Catholic bishop in Ruyigi, Burundi, and asked for money. Her request was the result of an immediate need: new clothes for her children, a Burundian Christmas tradition. Maggy had no money and 200 children in need of new clothes — young orphans who had fallen into her care since the outbreak of a civil war now in its second year.

The war had started in October 1993, when a group of Tutsi officers in the Burundian military assassinated the duly elected Hutu president. What followed was an ethnically charged civil war between Hutu and Tutsi that killed as many as three hundred thousand Burundians and created twice that number of orphans. By December 1994, the number of children in the care of “the crazy woman from Ruyigi” was close to seven hundred.

Only the youngest children needed new clothes, but they all needed food; and if the people of Ruyigi had come to see Maggy as crazy in that first year of the war, her constant hunt for food was a contributing factor. When the war started, Maggy was thirty-seven years old and had long been someone who spoke her mind. She once explained this character trait by saying, “We have to let our tongues loose and speak. If I do not criticize, it means I do not love. There is no love without truth.”

The opening months of the war altered the terrain of love and truth in Burundi and transformed Maggy. “I became really crazy because every morning I had to find food. Sometimes I lied. I needed milk for the babies, and so I would go to the corner store and take milk and say, ‘I will pay you later.’ When I didn’t pay and they came for their money, I hid and had the children answer the door. And early in the mornings I went to the fields with children to take corn and other vegetables. We had nothing to eat. I was not afraid to lie. Even to steal.”

When the police caught her stealing from fields on public land, she would argue. “You shouldn’t try to stop me. You must do this every morning with me. Help me. It’s not a crime. It’s a lesson that I give you. It’s for your children.” The police were not persuaded. “They wanted to humiliate me because I am from a prominent family, and they knew me before the war. I was driving a car. I was the secretary of the bishop. I had studied outside the country in Europe. And here I was in this moment, no shoes, no clothes, stealing corn. Sometimes they beat me.” Once when the police were beating Maggy, she called out to the children to beat the police, and the children started pelting them with stones. “People came to see. ‘Look, Maggy’s beating the police.’” Maggy laughs as she tells the story.

Bishop Joseph Nduhirubusa turned down Maggy’s request for new clothes for the children. He said the diocese simply didn’t have the money. Maggy was undeterred. She knew the bishop had recently put new decorative curtains on his windows, so she slipped into his residence, went into the great hall where he entertained guests, and took down the curtains, leaving in place the lighter, opaque window coverings that hung underneath them. Her seamstress friends then used the material to sew new clothes for the children. When Christmas came, Maggy took the children to Mass dressed in their new clothes. The bishop was presiding. He didn’t recognize his curtains.

No one noticed that the children were wearing the bishop’s curtains until months later, on March 19. “I remember the day,” Maggy says, “because it was the feast of St. Joseph, and the bishop was having a celebration for his patron saint. I was invited and said I would come if I could bring my children.” When the children entered the great hall, a nun noticed that their clothes matched the bishop’s curtains. “The cut is the same as . . .” she started to say; then she noticed the missing curtains. She made the connection and berated Maggy for what she had done. Maggy replied, “But I did this in December. No one noticed in January or February and now it’s March. You didn’t see that the curtains disappeared because they are not needed.”

That’s the same response Maggy offered the bishop when he accused her of stealing his curtains. “No, bishop,” Maggy said. “I didn’t steal your curtains. I asked you to provide clothes for the children at Christmas, and you did.” Referencing the lighter coverings that remained on his windows, she added, “And look, you still have curtains.” In the years that followed, as the war raged and hundreds of children turned into thousands and thousands into tens of thousands, Maggy kept finding ways to keep pace with need. When asked how she did it, she would sometimes say, “Love made me an inventor.”

***

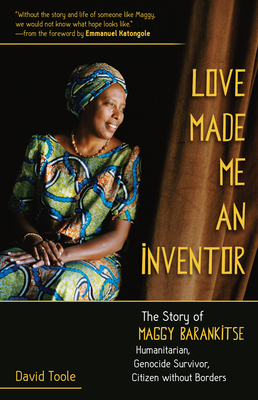

This book recounts the story of Marguerite “Maggy” Barankitse. In various circles, she is a well-known figure for what she has accomplished through Maison Shalom, an organization she founded in Burundi in 1993, in the opening months of the civil war. For more than two decades during and after the war, Maggy and Maison Shalom focused on caring for Burundi’s orphans. Then in 2015, after events in Burundi forced Maggy and the staff of Maison Shalom to flee the country, their work shifted to caring for Burundian, Congolese, and other refugees in Rwanda.

Despite its localized focus, the work of Maggy and Maison Shalom has not gone unnoticed throughout the world. In 2003, she received the World’s Children’s Prize for the Rights of the Child, an award Nelson Mandela would win in 2005. In 2008, she was selected as the laureate for the Opus Prize, a prestigious award for faith-based social entrepreneurship. In 2009, France gave Maggy the title Chevalier (knight) in the Legion of Honor — the country’s highest award for both military and civilian service. In 2016, a selection committee co-chaired by Elie Wiesel chose Maggy as the inaugural laureate for the Aurora Prize for Awakening Humanity, “a global humanitarian award recognizing those who risk their own lives, health, or freedom to save the lives, health, or freedom of others.” Both the Opus Prize and the Aurora Prize are $1 million awards.

Search Google and you’ll find countless stories about Maggy, who turned 69 in July 2025. But aside from short media pieces, a handful of documentaries produced at various points in time, and one outdated biography published in French in 2005, no one has captured the full intricacies of her life and work. “Love Made Me an Inventor” is my attempt to do that, with the caveat that I did not set out to write a comprehensive biography. What I have tried to do instead is create a portrait of Maggy.

When I say I have written a portrait, I have in mind the qualitative research method Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot and Jessica Hoffmann Davis described in the 1990s as portraiture. I am not a social scientist, and this book is not a work of social science. Nonetheless, what Lawrence-Lightfoot and Davis said of portraiture is a fitting description of my approach to writing about Maggy:

“Portraits are shaped through dialogue between the portraitist and the subject. The encounter between the two is rich with meaning and resonance. A sure intention in the methodology of portraiture is capturing — from an outsider’s purview — an insider’s understanding of the scene. The portraitist is interested not only in producing complex, subtle descriptions in context but also in searching for the central story, developing a convincing and authentic narrative. The process of creating the narrative requires a difficult vigilance to empirical description and aesthetic expression.”

Vigilance is required, they suggest, because portraiture, by design, “blurs the boundaries between aesthetics and empiricism in an effort to capture the complexity, dynamics, and subtlety of human experience.” In crafting my portrait of Maggy, I spent considerable time on empirical due diligence, chasing down the facts of her life; but this book is an aesthetic undertaking anchored in a dialogue I have had with Maggy over the course of 15 years.

Excerpt from “Love Made Me an Inventor: The Story of Maggy Barankitse — Humanitarian, Genocide Survivor, Citizen without Borders” by David Toole (Orbis Books, 2025). Used with permission.